Impact of the Global Financial Crisis on the Asia Pacific Region and Economic Outlook

The US sub-prime mortgage crisis has turned into an international financial crisis but it is not yet certain that the ensuing global downturn will result in a severe recession in Asia. Asian economies have been hit as hard as industrialized economies by a sharp decline in financial asset prices and by the credit crunch. However, economic growth in greater China and parts of Southeast Asia remains positive, and many Asian governments have fiscal and monetary tools at their disposal to mitigate any further deterioration in their economies. This is not to say that there has been a “decoupling” of Asia from western industrialized economies. Indeed, the export outlook has dimmed considerably for major Asian economies, and the effects of falling export demand have already led to sharp employment losses. But Asian economies have relatively strong banking systems and large foreign reserves, which puts them in a much better position than in the 1997- 98 financial crisis. Even so, downside risks weigh heavily in the current forecast, which is predicated on the positive impact of the US and other liquidity injections taking effect in the first half of 2009, resulting in a modest recovery.

The fall in energy and other commodity prices will sharply reduce the import bill of Asian economies, while the depreciation of their currencies relative to the US dollar will improve the competitiveness of manufacturing exports. If anything, the recession in the United States will accelerate the pace of demand switching in Asia and of deeper regional integration and cooperation. Looking out five years, one of the likely consequences of the current financial crisis is that Asia will sell relatively more of its goods and services within the region, and less to the US and EU.

In the near term, the focus for Asian governments will be to defend against further contagion effects of the US financial market and credit crisis. In addition to monetary measures aimed at providing liquidity to credit markets and guarantees for domestic financial institutions, there will also be a series of confidence measures to boost demand through government spending. The recent $600b fiscal stimulus package by China is an example of how worried Beijing has become, but it is also an example of the Chinese government’s ability to provide fiscal stimulus at a time when the economy is in dire need of it.

Looking beyond the immediate crisis, the spotlight will turn to surplus countries in Asia, where an estimate $4 trillion in foreign reserves is held, about half of which is in the People’s Republic of China. The global recycling of surpluses held by Asian and Gulf states will take on greater urgency as funds are needed to recapitalize the US banking sector and to finance the massive deficits of the US government. While the US dollar has risen sharply since the crisis (because of a flight to quality), the medium term outlook for the greenback is more gloomy. With the US dollar at current highs, the temptation for Asian central banks to diversify away from the US dollar in the year ahead will be greater than ever. As the credit crunch eases, interest rates in the US will have to rise in order to attract investment capital from the rest of the world.

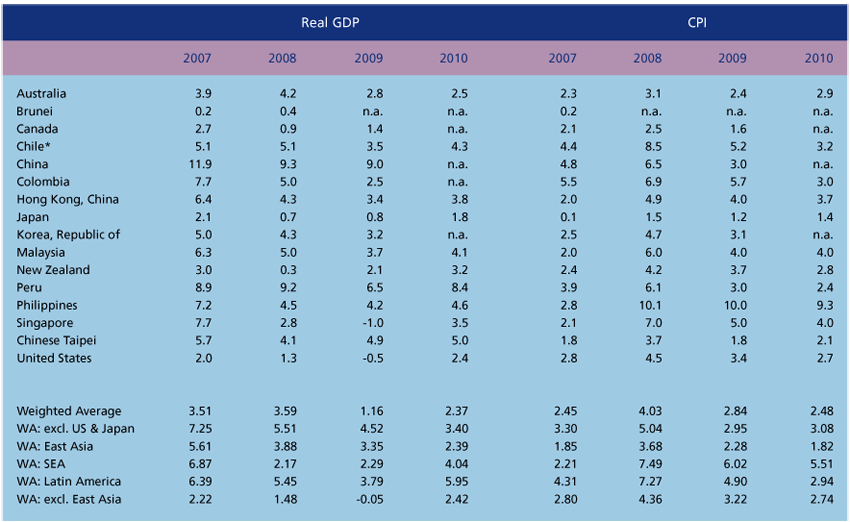

Asian economies of course are not monolithic, and different parts of the region are responding differently to the financial crisis. Japan does not have a financial sector crisis (indeed Japanese banks have done well to pick up the assets of failed or troubled US and European investment houses). Even so, the Japanese economy has only recently come out of a prolonged deflation, and is again facing the prospect of falling prices as a result of the slowdown in global growth. Unlike other Asian economies, Japan has little flexibility in its monetary or fiscal policy, and is very likely to show negative growth for part of 2009. Real GDP growth for the year as a whole is expected to be 0.8 percent, rising to 1.8 percent in 2010.

In contrast, China will continue to show growth of 8-9 percent in 2008 and 2009 because of stronger domestic demand, led by government spending. However, a fall of just one or two percentage points in GDP growth is sufficient to result in massive job losses, particularly in export industries that are concentrated in the southern coastal areas. Rising unemployment in urban areas comes at a time when the authorities are already struggling to improve the livelihoods of rural residents. These internal pressures will do more to increase the importance of domestic consumption and investment in total output than any amount of hectoring from the west. There is a strong risk that the fall in exports will be more severe than expected and that the fiscal package will not be enough to compensate for falling external demand, especially in the areas where export processing is concentrated.

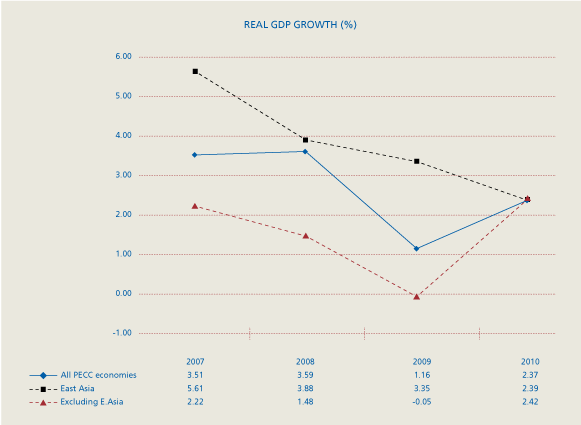

The Pacific Economic Cooperation Council expects real GDP growth for the Asia Pacific region as a whole to be in the order of just 1.2 percent in 2009, compared to around 3.5 percent in 2007 and 2008. This sharp decline in output growth will be led by the United States, which is expected to experience an economic contraction in 2009 of around 0.5 percent. The U.S. economy has been on the cusp of recession for a year or more, as it absorbed the bursting of the housing bubble and the surge in oil prices. Until the late summer, it wasn't clear that the economy would actually slip into a classic recession in which the economic doldrums spread broadly through all the major macroeconomic indicators of employment, income, and production. The financial crisis—stemming from the housing bubble and the extraordinarily unwise overinvestment in mortgage backed securities and related derivatives—which hit the world’s major financial institutions in September has altered the balance of events in the U.S. economy.

With the freezing of credit markets, the US has now tipped into what will undoubtedly prove to be a significant economic recession. Our forecast has U.S. real GDP declining for three straight quarters, 2008q3 through 2009q1, followed by a modest economic recovery beginning in the spring quarter of 2009. A period of three straight quarters of declining real GDP has not occurred in the U.S. since 1974-75, and not even in the 1981-82 recession that is generally regarded as the most severe in the post-WWII era. However, the severity of the current recession doesn't compare with the recessions of 1981-82 and 1973-75. The forecast posts a total loss in real GDP of just 1.4 percent over the three quarters of decline, which is close to the magnitude of contraction that was seen in 1990-91.

US unemployment is forecast to peak at about 7.5 percent in late 2009. The payroll job count is expected to improve by 1.2 million during 2010 (4th-Qtr-to-4th-Qtr), following losses of 1.1 million jobs in 2008 and 1.4 million in 2009.

T1: Real economic growth and increase in consumer prices for PECC economies, 2007-2010 (%)

*Statistics from provided by UniversidD de Chile complements the update from the Central Bank of Chile.

Note: National currency based. The weighted average is based on the respective economies’ 2004-2007 Nominal GDP (see T9).

Source: SOTR forecasters

The biggest uncertainty in this forecast is whether the worldwide array of policies aimed at thawing the credit freeze will have their intended effects and how long it will take for these measures to have effect. We have assumed that the size of the liquidity programs envisioned and the coordination of efforts now under way among the major economies and their central banks will result in sufficient improvement in the next few months to promote modest economic recovery in the U.S. beginning in the spring of next year.

East Asia is forecast to show real GDP growth of 3.4 percent in 2009, about half a percentage point lower than in 2008. Inflationary concerns which dominated the headlines in the first half of 2008 have largely abated, with consumer prices expected to increase by 2.3 percent in 2009 after an increase of 3.7 percent the previous year. With the exception of Chinese Taipei, all East Asian economies are expected to have slower growth in 2009 compared to 2008. Singapore is forecast to show negative growth in 2009, followed by a modest recovery in 2010.