Regional Organizations

A major objective of the APEC process is to improve the well-being of the peoples of the Asia Pacific through closer economic integration and regional cooperation. There is no single measure of regional integration. It can refer to the participation of the region in global integration, the growth of a regional identity expressed in tangible institutions and processes, or the integration among some of the economies of the region.

Regionalism and Regionalization

A common distinction is made between “regionalism”, understood as governmentpromoted regional cooperation expressed in institutional forms, such as ASEAN or APEC, and “regionalization,” defined as growing economic interdependence that is a result of private sector trade and investment decisions. Asia Pacific regional integration is often contrasted with the European integration process in that it has been led and dominated by regionalization rather than regionalism.

While regionalization continues to move ahead very rapidly, regionalism is more fragmented and uncertain, partly because the region is so vast and differentiated and partly because of the priority many governments attach to sovereignty and national development objectives.

Twenty years ago, the institutional landscape of the Asia Pacific region consisted of sub-regional bodies in the Americas, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific, but not a single body promoting economic integration and cooperation for the Asia Pacific as a whole. Created in 1989, APEC is now the principal vehicle for governmental promotion of transpacific economic integration and cooperation. In the past decade, it has been joined by the ASEAN Plus Three forum, which held its first leaders meeting in 1997, and the East Asia Summit process, dating from 2005. There is substantial overlap between APEC on the one hand, and the APT and the EAS on the other, with the principal difference being the exclusion of Eastern Pacific economies from the newer fora.

While APEC has the broadest membership and the most developed work program, it is also largely confined to voluntary economic cooperation and is not a negotiating or rule-making body. The development of APEC as an institution has been painstaking. Nearly two decades after the creation of APEC, efforts to strengthen the Secretariat are routinely met with resistance.

The ASEAN Plus Three and the East Asia Summit have broader mandates, including political cooperation. The ASEAN Plus Three has gone the furthest in forging free trade agreements among sub-groups of the membership and has also launched a range of long term “community building” initiatives. The EAS met twice in 2007 -- Cebu in January (originally intended as the 2006 meeting) and Singapore in November. It is beginning to be seen both as a venue for interactions among political leaders and as a mechanism for promoting cooperation on longerterm issues such as energy security and environmental challenges. Indeed, the theme of the Singapore meeting was “Energy, Environment, Climate Change and Sustainable Development” – a set of long-term issues that do not conform to the stereotype about Asian countries’ preoccupation with economic growth.

The agendas of new and old regional institutions alike have become increasingly long and complex. APEC, ASEAN plus Three, and the East Asian Summit all seek to address, in some measure, both economic and non-economic issues, from trade liberalization to domestic regulatory reform, contagious diseases to climate change, counter terrorism to human trafficking.

To date, however, all three organizations have not ventured much beyond leaders’ statements and the setting of lofty goals. Some capacity building has taken place, especially in the APEC context, but there is no systematic institutional commitment to technical assistance across the range of issues on Leaders’ agendas. Government officials, as well as the business community and general public, are increasingly bewildered by the proliferation of initiatives in various groupings. There does not seem to be a mechanism to coordinate overlapping activities and to eliminate the wasteful duplication of resources.

Effectiveness of institutions

Our survey of opinion-leaders demonstrates considerable dissatisfaction with the current state of regional organizations at both the transpacific and sub-regional levels. In general, APEC and ASEAN come out better than their younger siblings the EAS and the ASEAN plus Three. Only 30 percent of opinion leaders agreed that competition from the EAS was an important or very important threat for APEC. They were split, however, on whether APEC is as important today as it was in 1989, and they see nagging problems in both the institutional structure and focus of APEC, and in its lack of commitment from member economies.

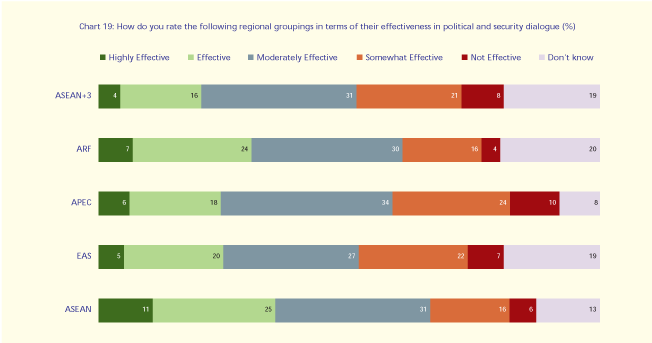

A majority of respondents gave an effective or highly effective rating to only two organizations, but this was for only one of six suggested activities for APEC (leaders meetings) and two for ASEAN (leaders meeting and community building). Only a quarter gave an effective or highly effective rating to APEC for trade facilitation and trade liberalization. All of the regional organizations were not highly regarded in the area of political and security dialogue. Even in the case of the ASEAN Regional Forum -- which comes closest to a venue for security dialogue in the region – only seven percent of respondents considered the grouping to be highly effective.

These results suggest that the region continues to face a major challenge in building and demonstrating the utility of its regional organizations. Some dimensions of this challenge include: (1) how to develop effective political and security cooperation as complementary to economic cooperation at the broader Asia Pacific level, given the limits of the current APEC process, (2) how to mature the East Asia region building process, given the overlap of the two major organizations and different views about the geographical and functional scope of these organizations, (3) how to mesh cooperation at different sub-regional, regional, inter-regional, and global levels, and (4) how to be inclusive opinion leaders identified a “weak international secretariat” as a very important or important challenge for APEC. Further, when asked if the APEC Secretariat should be strengthened by appointing a multi-year fixed term Executive Director and the recruitment of professional staff, respondents (in organizations such as ASEAN which covers all of Southeast Asia) and yet develop an effective work program, given marked differences in economic development, commitment to regional cooperation, and in political values and systems.

APEC Issues

Because of its relevance to transpacific regional integration, PECC gave special attention to the development of the APEC process. Three issues stand out: institutionalization, membership, and the trade liberalization agenda.

Our survey suggests strong support for greater institutional development of APEC. Nearly half of answered overwhelmingly in the affirmative. Indeed, respondents identified “Strengthening the APEC Organization” as one of the top five priorities for the grouping. In this context, the announcement coming out of the Sydney Leaders’ meeting to recruit professional staff to the Secretariat and to increase its budget are signs of members’ commitment to institutional strengthening.

Another unresolved issue is membership. In Sydney, APEC Leaders in effect decided to keep the moratorium until 2010. In the meantime, APEC members will once again attempt to formulate a set of principles that are sufficiently elastic to justify the existing membership, yet not so openended as to create false expectations among potential applicants. The application of any criteria, however, will in practice be subject to the narrower calculations of existing members — some with louder voices than others — as was seen in the last round of new admissions. As of 2007, those interested in membership include India, Pakistan, Macao, Mongolia, Panama, Colombia, Sri Lanka, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Cambodia, in no particular order.

Leaders are reluctant to increase the number of members for fear of making the organization even more unwieldy. As it is, consensus on even mundane issues has sometimes been difficult to achieve. Our survey respondents share this reluctance, listing “expansion of membership” as 16th in a list of 17 possible priorities.

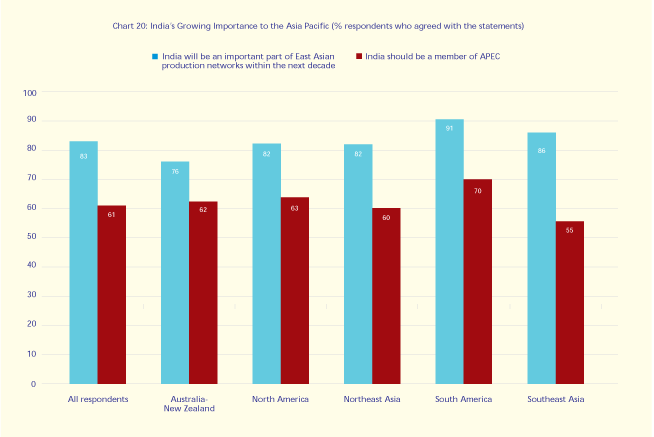

However, the case of India is distinct. Because of its size and geopolitical importance, India’s membership would significantly change APEC. India has committed itself to economic liberalization of the kind envisaged in APEC’s traditional criterion for membership. Skeptics still question the durability of India’s commitment to openness, but the reform process in India is probably now as secure as China’s “open door” policy was at the time Beijing was admitted into APEC in 1991.

When asked if India should be a member of APEC, 60 percent of survey respondents agreed. An even stronger majority agreed with the proposition that India “will become an important part of East Asian production networks in the next decade” even though this is as much an argument for membership in Asia-only institutions as it is for membership in a transpacific forum.

APEC recently completed a mid-term review of its progress towards the Bogor targets of “free trade and investment in the Asia Pacific by 2010 for developed economies and 2020 for developing economies”. While the review outlined credible achievements in particular areas of liberalization and facilitation, it also made clear that the Bogor goals will not be achieved. The Individual Action Plan and Collective Action Plan processes provide collegial discussion on how individual economies are making progress towards collective goals in economic integration, but they provide no mechanisms for enforcement.

The failure to meet the Bogor goals does not in itself invalidate the importance of APEC, but it does raise questions about the comparative advantage of the regional forum in advancing trade and investment liberalization and facilitation. Is APEC’s role principally that of a cheerleader for the successful conclusion of multilateral trade negotiations? Can APEC make a useful contribution in its model measures for FTAs? What additional trade facilitation projects can APEC initiate, without turning to binding agreements? Should APEC strive for a formal regional trade agreement such as the FTAAP? As APEC comes to terms with its inability to meet the 2010 Bogor deadline, the challenge is to find a new way of articulating the organization’s raison d’etre and new approaches for promoting more open trade and investment in the region. Our survey results confirm the commonly-held perception that APEC members lack commitment to the organization. In this sense, the most serious threat to APEC ultimately will not come from a competing organization or from the failure to meet the Bogor targets, but rather will be due to a lack of will from within to revive itself.

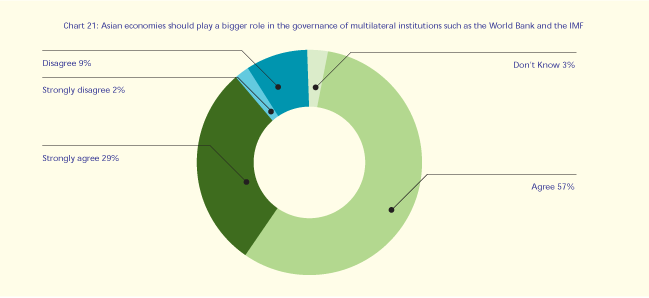

One area in which there is strong agreement among opinion leaders is the need for Asian countries to play a larger role in the governance of key international bodies. On the one hand, the current architecture of global economic governance is based on power sharing between the United States and Europe, and is resistant to a larger voice from emerging countries, including Asian powers. On the other hand, Asian governments have until recently placed little emphasis on international governance issues, preferring to focus on domestic economic development and political stability. Both of these factors are changing, and the result is a challenge to the status quo powers not unlike the emergence of the United States in the interwar period.