Chapter 3 - Economic and Technical Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific

The results of PECC’s annual survey of opinion-leaders in Chapter 2 reveal some serious concerns over the ability of the region to continue on its path towards regional economic integration. While showing strong support for continuing work on trade and investment liberalization and facilitation, respondents from emerging economies highlighted the need for supply side improvements to ensure that they get the most out of the integration process.

The first section of this chapter develops the case for taking a value-chain approach to economic and technical (‘ecotech’) cooperation in the region noting key recommendations from various independent assessments of previous activities. The second section looks at lessons that can be learnt from the aid for trade process.

Section 1: Goodbye to Festina Lente*

* Contributed by Federico M. Macaranas, Professor, Asian Institute of Management, Manila, Philippines.

This paper develops the case for a new vision of economic-technical cooperation (ecotech) in the Asia-Pacific region. This new approach aims to meet rising expectations on the delivery of outputs and outcomes benefiting various publics / stakeholders via the faster delivery of tangible results – within shorter-term rather than medium- or long-term timeframes; if not possible, the communication should center on which part of a series of value chains an activity of an APEC group is contributing to. This requires a mapping exercise to connect activities to each other in business production logic. The value proposition of an APEC Ecotech program is in providing both thought leadership and cutting-edge, knowledge era management skills to enable stakeholders to adjust and benefit from the rapid changes that take place in a knowledge economy.

In today’s knowledge era, there is an increasing need for academic institutions and think tanks to work with governments and businesses in the implementation of the programs that come out of regional policy dialogues and capacity building initiatives.

One might characterize the regional cooperation process in the Asia-Pacific as festina lente (making haste slowly). The rapid proliferation of activities and the slow pace of actual outcomes leads to a perception of a lack of effectiveness of regional institutions making the oxymoronic proverb “festina lente” an apt description. Indeed, more short-term quick wins are expected by netizens of the world today, in part due to technology being seen as an expediter for the “dispatch of efficient business ‘versus’ the slowness of careful reflection.”

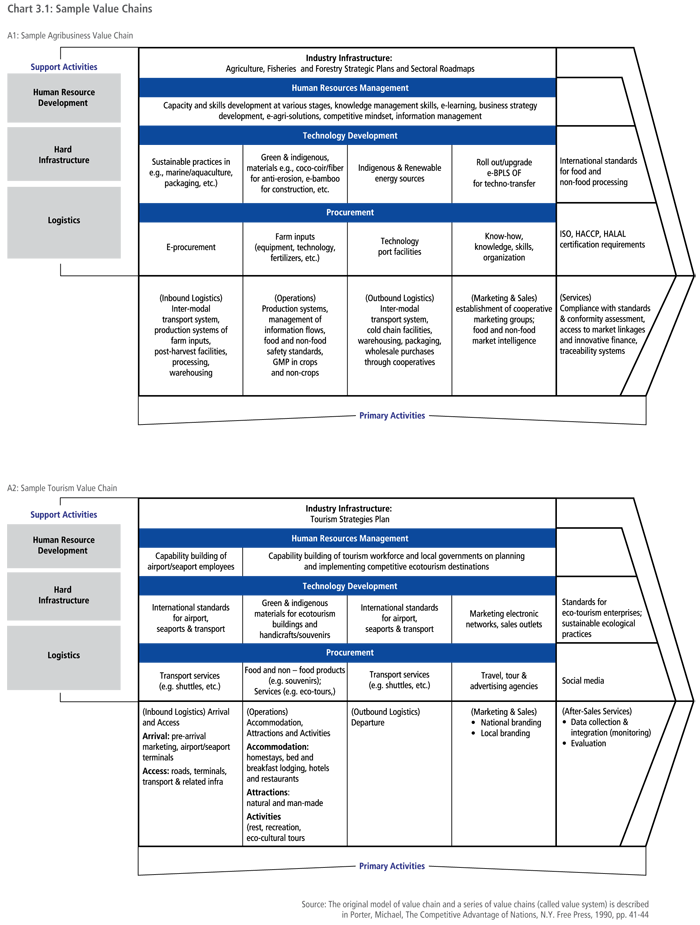

Ecotech cooperation in APEC certainly is one example of the seeming hastiness in adoption of multifarious activities of various working groups and fora but whose perceived slowness lies in the delivery of tangible outputs and outcomes to the businesses and households of the Asia-Pacific. The latter is directly due to the absence of a value chain and mapping approach in connecting activities to outputs directly perceived by the beneficiaries as adding to their welfare. The slow process orientation of intergovernmental organizations is in direct contrast to the hasty demands for direct impact on the lives of those governed (see Chart 3.1 for sample value chains).

This approach would enable APEC to focus its many activities, which have been broadened in successive yearly summits, with the endorsement of leaders, ministers and senior officials of more ecotech projects, for example. The rethinking for a hastened implementation of ecotech cooperation is made imperative by the global economic restructuring that requires a more equityconscious growth and development across and within economies. Phenomena such as jobless growth, continued poverty amidst rising financial/ real resources ratios, and widening gaps in top management and average worker compensation packages are forcing an examination of how more people can participate in the promised political stability, prosperity, and true community of regional groupings. APEC cannot afford to be bogged down by more reflection on these. Action is what it now needs.

Ecotech cooperation in any diverse grouping can be executed among and within developed and developing members, on matters directly supporting trade and investment liberalization and facilitation (TILF), or removing bottlenecks for sustainable economic development. Which avenue more quickly helps in building the credibility of an organization is largely contextual; different industries and firms of member economies are in various stages of market relations – in intent, capabilities and results.

Value Addition in the 2012 APEC SOM Report on Economic and Technical Cooperation

A review of this document suggests the need to communicate urgently the various achievements of ecotech in APEC short of the grandiloquent outcomes enunciated by leaders. This should be expressed more in terms of the final outputs expected by businesses and households, such as jobs - additional, appropriately trained, highly productive, more secure, etc.; basic needs – the availability and accessibility of quality food, water, clothing, shelter, health, education, human security, etc.; equitable distribution ofopportunities to produce income and wealth; innovative goods and services appropriate to the ICT age. One parallel that might be drawn is the impact that the European Coal and Steel Community had on new agriculture products and manufactures in the early European integration efforts. The modern equivalent should consider the minimized risks of the various crises of the new century – environmental, physical, financial, and so on.

Such outputs relate to the Leaders’ vision (outcomes) and APEC fora activities (processes) as supported by member economy inputs of human and financial resources, and the administrative support of a secretariat. In the realm of inputs for ideas in managing a complex organization, technical management concepts are in order.

Value chain and mapping exercises

APEC’s SOM Steering Committee on Ecotech Cooperation (SCE) can play a key role in the development of a value chain and mapping approach that connects the various intermediate outputs of activities to these final outputs. This value addition of APEC is what stakeholders could appreciate more deeply in the Leaders’ Statement from the annual summits. The credibility of APEC as an effective cooperation mechanism must be strengthened especially by 2015 when Millennium Development Goals are finally assessed. In fact, all APEC ecotech fora are supposed to submit their strategic plans by 2013 for deliberation in SCE-Committee of the Whole (COW) by 2014. How has APEC contributed to the fulfillment of the MDG targets, for example? This is not an unfair question to ask of leaders and ministers after all, given the acceptance of ecotech cooperation as an equal leg as its TILF agenda. Consider the progress report on the APEC Growth Strategy in the 2012 SOM Report on Ecotech. Leaders have requested Senior Officials to conduct “annual progress reviews on APEC’s relevant work programs while finding ways to take stock of progress” (italics not in original text). The value chain and mapping approach is a most appropriate way to take stock of APEC’s growth, whether more balanced, inclusive, sustainable, innovative or secure, in terms of specific stakeholder objectives, eg more jobs and higher incomes. This is what “taking stock of progress” means to ordinary citizens, businesses and consumers.

Some examples

There are numerous examples in past APEC ecotech work that could have real impacts on people’s lives at various time periods. For example, a study of the Mining Taskforce on the impact of EU classification of nickel compounds on APEC economies falls under the balanced growth strategy; taken in combination with work on corporate social responsibility in the mining sector, a single valuechain would give a powerful narrative of showing APEC response to constituencies in the industry since the two projects impact at different points in time.

Similarly, the Human Resources Development Working Group (WG) projects on measurement and teaching of higher education in APEC (under ‘balanced growth’) can be combined with the APEC basic entrepreneurial course possibly through distance learning (under ‘inclusive growth’) and the emergency preparedness education programs (under ‘secure growth’), also in one value chain for jobs generation. Again, these may impact lives non-contemporaneously.

On the general theme of food security, the Ocean and Fisheries Working Group (OFWG) project on small pelagic fish as source of high-quality protein (under ‘sustainable growth’) can be combined in one food value chain with the same OFWG roundtable on shaping ocean and coastal management (under ‘inclusive growth’) and seminar on satellite data application for sustainable fishery support (under ‘innovative growth’). The APEC household consumer as ultimate beneficiary is interested in being informed on how some of these can be achieved more quickly than others, and indeed, if at all, some are prerequisites to other activities. When will there be more food on the consumer table on account of the APEC?

Some activities under one forum may require different value chains, eg illegal logging identification and forest fires monitoring being undertaken by the Industrial Science and Technology Working Group (ISTWG) in one project (under ‘sustainable growth’) may impact incomes of different constituencies. These necessarily involve different value chains for income security of two stakeholders. For example, the Agricultural Technical Cooperation Working Group (ATCWG) project on innovation to increase food productivity impacts both household consumers as well as feed to the dairy industry; of course they eventually contribute to a farm-to-plate metric, albeit at different time frames.

Capacity building for systems thinking

Indeed, the 2012 SCE Workplan (Annex 1) calls for: a “stocktake capacity building needs”; greater engagement with other international organizations and the Asia-Pacific business community (second proposal), “work on cross-cutting issues and its coordination among and across fora” (third proposal), and the “development of a strategic planning document by fora.” A value chain and mapping approach is once again the evident answer to link current efforts to the expectations of the general population on what regional public institutions are supposed to deliver – information and interventions in the nature of public goods towards the attainment of their vision6. Capacity building in stocktaking must include a systems thinking ability, which the value chain and mapping exercises can generate, including the other workplan requirements cited above.

On the matter of crosscutting issues, the obvious need for the value chain and mapping framework surfaces even more prominently in Annex 4. All the six areas described (SCE-COW Policy Dialogues, Joint Meetings of SCE fora, Joint Activities, Joint Projects, and Inter-sessional Communication) are merely administrative approaches and not management frameworks that address perceptions of present delivery of intermediate outputs that will eventually lead to final goods and services expected by businesses and households.

In fact, the revised guidelines for Lead / Deputy shepherd / Chair include, among others, “the coordination of a medium-term strategic plan aligned with the organization’s overall objectives” as well as ensuring “that project oversees work with APEC Secretariat communications team to provide a write-up of the projects’ accomplishments and planned follow-up.” These look administratively simple until one examines how complex the effective delivery of expected outputs is using a systems approach.

Value chain and mapping help connect the dots from the scores of activities and various crosscutting issues of several APEC fora. Here is where the academic and business sectors can come in to help shape the systems thinking which guide the logic of general equilibrium models. The tasks of the Lead / Deputy shepherd / Chair thus need to be spelled out more carefully by the SCE Committee of the Whole even before its 2014 review of the strategic plans. Early harvests of low hanging fruits and quick wins can be identified somewhere along the value chains; while they need not be the final outputs desired by businesses and households, they should somehow contribute to their realization at some future promised date.

However, as currently designed, the APEC Secretariat may not be able to extend the level of assistance for systems thinking in this regard. The Program Directors of APEC “are usually officials with different backgrounds and experience and may not possess technical expertise in the particular subject area of the forum…” yet they are tasked to assist the Chair / Lead Shepherds by “providing advice as to how the sub-fora could incorporate the Leaders’ and ministerial directives into their work plan.7 The APEC Secretariat does have a Project Management Unit (PMU) established in 2007, which could take on this role. The PMU is charged with improving management systems and building capacity for submitting project proposals. With its role within the APEC Secretariat in the project process it could be one place where a value-chain and systems approach could be developed, perhaps with input from various stakeholder groups such as ABAC, the APEC Studies Centers Network, and official observers including PECC, ASEAN and the PIF. However, taking on an expanded role would entail dedicating more resources to the PMU.

The SCE is the natural owner of the capacity building efforts on systems thinking since its Terms of Reference (May 2012) include the prioritization and effective implementation of ecotech activities, providing oversight on the work of APEC fora, and policy guidance to contribute to ecotech goals. Its mandate spells out the coordination of action-oriented and integrated strategies, including the realignment of individual work plans and ranking of all ecotech-related projects before presentation to the Budget Management Committee (BMC).

Independent assessments of ecotech implementation

The 2012 APEC SOM Report on Ecotech Cooperation contains recommendations to the SCE by independent assessors that point towards the above value chain and mapping exercises to foster a systems thinking in APEC. By working backwards, ie starting with the APEC end goals or grand vision in mind, ecotech implementation can be made more consistently coherent and address the perception of APEC’s effectiveness in delivering outputs to specific stakeholders.

For example, the assessment of the Telecommunications and Information Working Group (TELWG) specifies the need for a detailed work plan with clear objectives and a target audience. It also notes that there are at least 5 other working groups that undertake complementary activities. In the case of the Agricultural Technical Cooperation WG (ATCWG) and the High-Level Policy Dialogue on Agricultural Biotechnology (HLPDAB), the independent assessor recommended that the group “develop and deliver educational packages for agricultural technologists in research, promotion, communication and dissemination; and policy practitioners in research assessment, management, and utilization” (#9).8 Such direct specification of stakeholders can now be linked to the ultimate business and household beneficiaries who want the final products of such exercises (real goods and services) rather than the research and policy outputs, albeit important as they are.

Examples from Independent Assessment of Ecotech Implementation

The assessment of Telecommunications and Information Working Group (TELWG) recommends to the SCE, “a more detailed plan with clear objectives, expected outputs and the targeted audience.” Moreover, it explicitly states that at least 5 working groups have activities complementing those of TELWG. The suggestion is for “SCE to consider further guidance that can be provided to the fora to encourage greater alignment with overall APEC objectives.”9

The independent assessor’s fourth recommendation to the TELWG itself is for “a clear definition of expected outcomes from TELWG activities (to) permit the member economies to identify the targeted audience.”10 The eighth recommendation to the TELWG itself is the elaboration of a roadmap to organize future topics – which hopefully relates to the chain of activities connecting to the final desired outputs of the working group.

On the Anti-Corruption and Transparency Working Group (ACT), the independent assessor’s second recommendation to the WG itself is “to include a table listing the proposed activities to be addressed for the relevant period… to include reference to the link between the particular activity and the Terms of Reference of the ACT.” The tenth recommendation is “to review the current Terms of Reference of all other APEC Work Groups and Taskforces to identify any potential synergistic relationships,” while noting in other recommendations that ACT “differentiate its activities from similar organizations” (#14), “capitalize on its unique positioning” (#15), and “enable quantitative and qualitative measurement of all ACT projects and/or programs” (#16). These are surely supportive of a value chain and mapping exercise for ACT.

On the Agricultural Technical Cooperation WG (ATCWG) and the High-Level Policy Dialogue on Agricultural Biotechnology (HLPDAB), the independent assessor recommended, “engagement strategies between the technical and policy fora … to be incorporated into annual and medium-term plans… (including) formal cross-cutting interactions through examination of opportunities for collaborative projects/programs” (#5), and the development of joint policy papers on new and emerging technologies and policy challenges to achieve evidence-based regulatory harmonization for agricultural biotechnology based products. Outcomes and consensus positions should be developed and communicated to APEC SOM and Ministers” (#8). Interestingly, a suggestion was made “to develop and deliver educational packages for agricultural technologists in research, promotion, communication and dissemination; and policy practitioners in research assessment, management, and utilization” (#9).11 Such direct specification of stakeholders can now be linked to the ultimate business and household beneficiaries who want the final products of such exercises (real goods and services) rather than the research and policy outputs, albeit important as they are.

Finally, on the Policy Partnership on Women and the Economy (PPWE), the independent assessor recommended the adoption of “a strategic plan with a clear vision and objectives from which a Working Plan will be easier to define” (#1), the creation of a “Performance Chart which would include concrete variables of advancement on gender issues for both Member Economies and APEC fora to provide PPWE concrete tools to measure progress and success” (#2), “coherence of the agenda preparation” (#19), and inclusion in the PPWE Strategic plan of “a specific strategy to increase cross-fora cooperation” (#20). Here, it is important to stress what key result areas and indicators are needed to show how women participate in economies meaningfully, eg decent work and incomes in particular industries.

All of the four assessments clearly indicate the need for an approach beyond mere recital of activities when the state of regional cooperation in APEC is presented to the stakeholders. The value addition of APEC must be made more evident in thought leadership combining ecotech activities that ultimately benefit them; systems thinking can help locate the ecotech projects along a map of related value chains. These can thereafter be properly communicated to different audiences.

Ecotech Cooperation in Free Trade Agreements

Based on a survey of ecotech cooperation in twenty FTAs involving APEC member economies, some observations pertinent to the value chain and mapping approach for systems thinking are summarized here. One common issue in all of the observations below is whether the identified ecotech activities would have happened independently of APEC or the contracting parties in bilateral arrangements, either through pure market forces or some other regional effort. APEC’s or bilateral partners’ value addition is critical to an assessment of the effectiveness of pursuing separate agreements.

- Given the gaps in human resources, physical and financial capital, knowledge base and technological development between and among contracting parties, ecotech cooperation in FTAs naturally complement global trade strategies inherent in TILF activities. Ecotech cooperation in FTAs provides for complementary resources and activities designed to strengthen regional players vis-à-vis other parts of the world. The drive for cooperation for improving the economy for domestic markets and nonglobally tradable goods and services is naturally less pervasive as in economic cooperation agreements or economic partnerships designed to narrow development gaps across countries.

Consider the TILF-related cooperation provision in AFTA. This is accompanied by a Framework Agreement on Enhancing ASEAN Cooperation signed on the same day in Singapore and explicitly based on the principle of “economic cooperation through an outward-looking attitude so that their cooperation contributes to the promotion of global trade liberalization.”

Indeed, sample projects falling under ecotech provisions in FTAs include training programs to strengthen trade-related policies to support sustained economic growth (FTA between US-Singapore) and Customs Directors consultation promoting the safety and facilitation of international supply chain (FTA between ASEAN and China). JICA experts are stationed in the Philippines for information analysis and customs modernization project (Japan-Philippine Economic Partnership Agreement). For the value chain and mapping exercise, it is important that individual economies examine the combined impact of various agreements on various stages of the sourcing of inputs, production, distribution, and after-sales services. Several value chains may have to be mapped if one stage involves production of certain inputs, eg natural resources that are later processed domestically or elsewhere. - The fundamentals of sustainable economic development are emphasized in cooperation on human resources development, infrastructure construction, small and medium-sized enterprises, and science and technology projects and programs. These provide higher-quality levels of inputs in the production of goods and services destined for both domestic and international markets.

Agriculture, forestry, fisheries and plantation-related activities are covered in the Japan-Malaysia Economic Partnership Agreement. JICA has an animal disease control project where regional laboratories that may be used by Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are identified (Japan-ASEAN Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement). More advanced economies cooperate on intellectual property (Japan and Singapore for a New Age Economic Partnership) and spread it to developing partners (Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement between India and Singapore).

The value chain and mapping exercises, as noted above, can be used by individual economies to aggregate assistance projects so that gaps in the chains can be filled in, especially for SMEs that need more technical assistance and capacity building. - Information networks are prominent in ecotech provisions in some FTAs, keeping with the spirit of moving Asia-Pacific economies in the knowledge age beyond natural resource-based inputs. However, there seems to be no appreciation of knowledge management interventions to improve the growing services sectors. A critical part of the post-industrial economy is the generation, dissemination, utilization and storage of useful information, which knowledge management addresses. Practical wisdom, defined as experiential knowledge, enables people to make ethically sound judgment, which leaders of the new millennium must possess.

In value chains, the quality of leaders matters not only for judging the goodness for organizations and society. They must grasp the essence of situations by delving deep into the nature and meaning of people, things and events. These are part of six abilities that two foremost Asian management thinkers suggest ‘wise leaders’ should possess. - The value chain production process issues in the ecotech provisions in FTAs include reduction in trading costs,16 encouraging innovation capacity building (including absorptive capacity), promotion of transparent, science-based functioning regulatory systems, co-investment in both parties’ resources, and improvement of cooperative efficiency through market incentives. Bilateral arrangements are of course easier to negotiate and implement than comprehensive agreements; they are proof of the “hastening” preference of many governments in economic cooperation.

SCE Ecotech Evaluation

The weighting matrix and the Quality Assessment Framework (QAF) criteria for ecotech do not show any consideration for a more unified approach to ecotech activities from various fora based on the systems thinking approach of value chains.

However, the criteria on relevance refers to “the priorities and objectives of the target group, the recipient member economies and APEC as a whole” – a good start for preparing a value chain backwards, by beginning with the end in mind; a further consideration for this criterion must be its ability to account for the target group’s importance in a larger system.

The effectiveness criterion asks for the “APEC value-add” but based on the evaluation of a single project. Precisely because of cost-effectiveness considerations, the synergies across different projects need to be synthesized in a programmatic approach, which incorporates activities of other fora.

The efficiency criterion is similarly remiss in recognizing that single projects must be combined with others to understand cost– efficiency through economies of scale and scope; there seems to be a hint in this criterion through the reference to “alternative approaches deliver(ing) the same result for less cost.” The impact criterion refers to what the project seeks to change, deliverables to key stakeholders reflecting APEC values like gender equity. By citing “the possible impact of external factors such as changes in terms of trade or financial conditions,” this criterion attempts to isolate the value added element of APEC within its control and those beyond its ability to shape.

However, the focus on evaluation of a single project makes it less capable of delivering a consistent message to businesses and households - that the leaders, ministers and senior officials do understand that the net impact of various APEC activities is what matters in the short, medium and longer terms.19 The sustainability criterion finally looks at a project independent of all other APEC projects. It asks “whether the benefits of a project are likely to continue” among others through engagement with key stakeholders. Obviously, the single project orientation must be complemented with a broader mapping of value chains along the lines of systems thinking.

Using a previous example from above, a farm-to-plate metric for food security must account for short-term wins at the agricultural research phase, to the commercialization phase including regulation, to the secure trade issues, and final marketing to people who may not be able to afford the products because of market access problems including poverty and geographical distribution imbalances due to logistics problems.

A similar example is presented here as a boxed story of an ASEAN project to which APEC can immediately link – to solve future pandemics more effectively.

Ecotech Cooperation in a Network for Drugs Innovation

Health matters in APEC should not be treated as mere trade and investment issues, but as core of ecotech cooperation in human resources as well. Viewed from the spirit of a more holistic growth and development concern, a productive workforce that contributes to regional economic progress must be the concern of APEC since health matters partake the form of regional public goods. The productive workforce inevitably adds to the welfare of the dependent part of any member economy whose health concerns can then be projected for national public goods consideration. However, when it comes to infectious diseases, all people in any economy, workers and dependents alike, must be seen as part of a regional, and even global, public good system. The threat of pandemics makes this public good issue a long-term as well as a short-term priority for APEC when existing resources can be reallocated to address more urgent concerns.

The benefits of strengthening the health research network with in APEC will not only be reaped by the region, but it will also create larger benefits on a global scale. As an example, the integration of ASEAN in an innovation network for drugs, vaccines, diagnostics and traditional medicine (called ASEAN NDI) strengthens its negotiation capacity and exploration of endowments and grants from international support groups and multilateral bank institutions to fast track the drug discovery process, a multibillion dollar, multiyear effort done in the traditional model. A more recent and important development is in product development partnerships which are forms of public-private partnerships in the R&D value chain which ASEAN can now promote more extensively as the pharmaceutical industry undergoes transformation. The strategic business plan for ASEAN NDI clearly states:

Neglected tropical, infectious, and communicable diseases

Within APEC, Southeast Asia has a share of about 9 percent of the global population. However, because of its wet and tropical climate, it accounts for over a fourth of the global burden for infectious and parasitic diseases due to its conduciveness to vector and water-borne illnesses. Moreover, climate change has resulted to the cross-border migration of previously localized diseases moving from rural to urban areas. Nevertheless, tropical diseases and tuberculosis are neglected at various stages of the basic research-commercialization phases of the production of quality and affordable drugs, vaccines, diagnostics, and traditional medicine; the three health-related Millennium Development Goals are still problematic in many Southeast Asian countries (MDG 4: reduction of child mortality; MDG 5: improving maternal health, and MDG 6: combating HIV AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis).

The neglect of tropical diseases is continuously raised at the World Health Assembly. The World Health Organization has therefore embarked on a global effort to encourage the development of regional innovation networks for drugs, vaccines, diagnostics and traditional medicine. After launching one in Africa in 2009 called ANDI, a similar network was organized in ASEAN in 2010 called ASEAN NDI, where strategic business plans have now been prepared. Other networks have been set up in China and India, among others. This is very important since the next pandemic is feared to be coming from Asia, a genuine concern after the SARS episode which demonstrated the need for quick regional action; indeed, within seven months of the first outbreak of SARS in 2003, the ASEAN-China cooperation produced a dramatic solution for the dreaded disease, also as Dialogue Partners of ASEAN took collective steps preventing what would have been a major global catastrophe.

Cooperation in research along the value chain

ASEAN has been promoting science, technology, and innovation (STI) in the region since 1997 after the implementation of Vision 2020, but the scholarly output has been limited in the areas of scientific publications, researches, R&D, and foreign direct investments that have not produced, for example, a vaccine for dengue, a major mosquito-borne tropical disease. Indeed, it is evident that there are gaps across the R&D value chain -- through clinical trials and translational research phases from proof of concept to commercialization. Ecotech cooperation in this regard is going to pay off handsomely for the regional economy and its global partners. Natural resources in some countries can be paired off with scientific expertise in others to produce affordable drugs, vaccines, etc.

All members of the ASEAN have national S&T plans, albeit some are more defined than others. However, they are not necessarily unified in terms of approach. The ASEAN NDI business plan calls for such internal coordination within ASEAN and welcomes the Dialogue Partners in activities along the entire value chain, including the private sector. APEC and ASEAN are well positioned to collaborate in this area, among others due to the Blue Economy agenda of the former which calls for exploration of Asia-Pacific’s marine resources; the Coral Triangle in Southeast Asia, home of the most bio-diverse marine life in the planet, is waiting to be tapped for products, eg conotoxin from cone snails which has led to the development of Prialt, a substitute drug for management of severe chronic pain in patients who need drug administration directly into the spinal fluid.

Conclusion

The impatience for demonstration of direct benefits beyond “talk shop” discussions is evidenced not only by the proliferation of ecotech activities in several APEC fora but also across bilateral FTAs. While many regional economic groupings aim for long-term free trade and investment regimes, the practical difficulties in negotiating more comprehensive arrangements require incremental successes in the short-term to engage more stakeholders in further integration efforts. Academic and business advice on a systems thinking approach in managing expectations of deliverables is now needed to narrow development gaps in Asia-Pacific, eg for the MDGs and the ASEAN Economic Community by 2015. Mapping a series of value chains that end in direct benefits in real goods and services, increased incomes and wealth, more secure jobs, safer cities, and other such outputs, aimed at specific target groups in the region, especially the poorest citizens and the enterprises least prepared for integration, is one example that will raise the credibility of regional institutions like APEC. Such benefits are what leaders must communicate to their constituents while all reflect on the more uncertain and complex future, which many still aver will be an Asia-Pacific century.

Section 2: Lessons from Regional Aid for Trade*

* Contributed by Michael G. Plummer, The Johns Hopkins University, SAIS and East West Center.

An interesting example in which the “value added,” discussed at length in the previous section, could be pursued in the ecotech context might be found in the form of the “aid for trade” initiative, launched at the 2005 WTO Ministerial in Hong Kong. As reviewed extensively in OECD-WTO (2011, 2013), aid for trade has hitherto made considerable progress in mobilizing resources to overcome supply-side constraints and infrastructural bottlenecks that inhibit participation in the international marketplace. This process is “demand-driven,” with recipient countries increasingly mainstreaming aid for trade in their development planning. With the Doha Development Agenda currently in a holding pattern, aid for trade provides a concrete approach to supporting development via multilateral cooperation. It is arguably the most important contribution thus far after more than a decade of multilateral negotiations under the Doha Development Agenda.

Regional aid for trade is particularly relevant to the many challenges faced by ecotech. The trade agenda of developing economies in general and Asian developing economies in particular is increasingly being pursued through regional economic integration and cooperation efforts. In many developing regions, fragmented markets inhibit trade and competitiveness. Regional cooperation is one way in which these markets can be enlarged, specialization can emerge, and risks can be shared.

Regional aid for trade can help developing economies benefit from existing and emerging trade opportunities via its ability to enhance the effects of regional cooperation. A regional approach to removing trade-related binding constraints, supported by national, multi-economy and regional strategies, can greatly augment the impact of trade flows. In fact, many competitiveness challenges are regional in nature. For instance, the trade performance of landlocked economies depends on the quality of the infrastructure in their neighbors.

Regional aid for trade flows are not only becoming increasingly important qualitatively but also quantitatively. As reviewed in OECD-WTO (2013), which uses data from the CRS database,27 regional and sub-regional aid for trade (hereafter, simply 'regional aid for trade') constitutes a relatively small share of total aid for trade flows, but it has been rising. In 2002-2005, which the OECD-WTO uses as a benchmark period, total regional aid for trade came to just over US$1.5 billion (on average) but rose to US$5.8 billion in 2011, growing from less than one-tenth of total aid for trade flows to almost one-fifth. “Building productive capacity” - which includes projects related to banking and financial services, business and other services, agriculture, forestry and fishing - has consistently been the most important sectoral component of regional aid for trade by far (about three-fourths of total disbursements). As this category is particularly of interest to the private sector, its rising importance underscores the importance of regional aid for trade to the business community engaged in regional integration in general and production networks in particular.

Still, many practical challenges remain in developing effective regional aid for trade. For example, national development plans generally have difficulties dealing with activities featuring strong regional or international externalities. Consequently, aid for trade programs that are best implemented regionally may not take place because the benefits cannot be fully appropriated nationally. Consequently, most of the focus in the aid for trade initiative has been at the national level.

In this chapter, we consider some of these practical challenges. First, we survey efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of aid for trade followed by analysis of some of the challenges faced by regional aid for trade. Next, we consider regional aid for trade in the context of emerging “mega-regional” arrangements. Finally, we draw some lessons from the regional aid for trade experience for ecotech.

Assessing the Effectiveness of Aid for Trade

The development assistance community, led by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the OECD, is placing an increasing emphasis on results-oriented development assistance, a priority that clearly should be equally important in the context of ecotech. The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005) aims at creating a “practical, action-oriented roadmap to improve the quality of aid and its impact on development.”28 It stresses the principles of ownership, alignment of objectives, harmonization, results and mutual accountability. As a follow-up, the OECD-DAC produced the report, Aid Effectiveness 2005-10: Progress in Implementing the Paris Declaration (OECD 2011), which evaluated progress to date29. In addition, the OECD also organized the OECD High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness, the fourth meeting of which was held at the end of 2011, in Busan, South Korea. Specific to aid for trade, the OECD-WTO Third Global Review of Asia for Trade (OECD-WTO 2011) focused on effectiveness-related issues in aid for trade, as is clear from its title, Third Global Review of Aid for trade: Showing Results. The results underscore the importance of not only evaluating projects for the “biggest bang for the buck” but also careful planning and keeping short-, medium- and long strategies in mind while formulating and implementing projects.

In order for aid for trade to be effective — particularly in a challenging budgetary environment — it is critical to identify priority areas in which aid for trade has a comparative advantage, and this is especially true for regional aid for trade. In other words, given the plethora of economic bottlenecks and problems in developing economies, where can aid for trade add the most value? The OECD, WTO, World Bank, and their partner international organizations and governments have undertaken many studies related to identifying binding constraints to trade, estimating the benefits of removing them, and offering recommendations in terms of optimal design, sequencing, and good practices in related policy formation. In general, the consensus from this work is that most developing economies do face significant obstacles in terms of taking advantage of the international marketplace due to a widevariety of microeconomic (eg infrastructural problems, energy shortages, trade-facilitation constraints, human-capacity-related issues, other market failures), macroeconomic (eg acute inflation, problems related to foreign exchange and the exchange rate), and financial (eg trade finance) inhibitors. Development and technical assistance designed to tackle these constraints, including aid for trade, has proven to be effective in helping reduce their negative effect on trade potential.

For example, OECD-WTO (2011) reviews a number of studies that underscore how aid for trade has improved trade performance by lifting binding constraints, particularly in low-income economies. Several examples include: (1) a USAID study on capacity building calculates that a US$1 increase in development assistance in low-income economies leads to an increase in exports of US$42 two years later; (2) the Commonwealth Secretariat estimates that a doubling of aid to trade facilitation leads to a decrease in the cost of importing by 5 percent and an increase of exports by 3.5 percent; and (3) the Economic Commission for Africa estimates that a 10 percent increase in aid for trade reduces exporting costs by 1.1 percent.

Moreover, there are many areas in which regional aid for trade can address bottlenecks to closer bilateral and regional integration, be it in the context of a formal regional accord or otherwise. Regional aid for trade can contribute to the identification of promising regional projects, help in their design, and contribute to their implementation, in partnership with participating governments and other potential stakeholders, including the private sector. Perhaps even more than other forms of aid for trade, the multi-economy dimension of regional cooperation requires that regional aid for trade projects emphasize strong “buy-in” from stakeholders as well as ownership.

In addition, regional aid for trade can be particularly effective in linking low-income economies to regional production networks and value chains, also a priority in a number of ecotech projects.31 As is frequently noted in PECC publications, regional production networks constitute an important new form of industrial organization that has been a key catalyst of international trade in recent years. The associated “fragmented” trade allows multinationals to take advantage of diversity of factor endowments and skill development in the region (and the world), which in turn integrates low income, middle-income and developed economies along the value chain. As infrastructure, institutional reform, and market-friendly trade and investment measures necessary to lure FDI associated with production networks create a more efficient trade and investment regime, a development strategy devoted to exploit these networks tends to have highly-positive knock-on effects in terms of spurring growth and development and facilitating moving up the value chain. A great deal of empirical work has been done on production networks and fragmented trade in the region (eg ADB 2008). Chart 2.4 of the PECC opinion survey (Chapter 2) underscores that opinion leaders believe that establishing “reliable regional supply chains” needs to be a priority at the APEC leaders’ meeting in Bali.

Regional Aid for Trade in Action in Asia

East Asia in particular has been by far the most active — and successful — region in mobilizing regional cooperation as a means of promoting fragmented trade and production networks. Hence, it has been an excellent candidate for regional aid for trade projects. Most Asian free trade areas (FTAs) have been bilateral in nature, which tend to be easier to negotiate than, say, larger memberships or deeper accords such as customs unions. The driving force behind regional cooperation in East Asia is market-based; FTAs are being sought in large part as a means to increase FDI flows to deepen existing production chains and promote new ones. While the vast majority of empirical studies on bilateral FTAs in Asia would suggest that these accords have had (or will have) a positive effect on welfare of their member-states, they have important shortcomings: since the driving force behind Asian regionalism pertains to fostering regional production networks, bilateral FTAs will always tend to fall well short of potential. Regional FTAs would be needed to optimize value chains and lower costs associated with, for example, rules of origin (via “cumulation”), create regional intellectual property standards, adopt regional trade facilitation measures, and so forth. It is important to note that these latter policies are “first best,” as all economies benefit, not merely partner economies. In this sense, it is very consistent with the APEC tradition of “open regionalism.”

Recognizing these constraints, Asia-Pacific economies have now launched negotiations to create mega-regional accords, namely, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a trend that has been called the “new regionalism” in the Asia-Pacific (Petri et al., 2012). As each would constitute approximately 40 percent of global trade, they will be highly significant new institutions in the global economy and will serve to undo many of the much-maligned inefficiencies associated with the FTA “Asian noodle bowl”. While the leaders’ opinion survey suggests that there is skepticism in the region regarding the ability of TPP and RCEP leaders to finalize these respective agreements, this should come as no surprise: they are extremely complicated and politically difficult endeavors (as are just about all worthwhile policy initiatives). Still, empirical studies suggest that these regional accords will have large effects on regional economic growth due in large part to the effect that the TPP and RCEP will have on FDI inflows and outflows, that is, in enhancing production networks. For example, Petri et al. (2012) uses an advanced CGE modeling approach to estimate the economic impact of the RCEP and the TPP as pathways to the APEC-supported concept of the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) in 2025.32 They estimate large gains for both tracks: the effects on the world economy would be small initially but by 2025 the annual welfare gains would rise to US$223 billion on the TPP track, US$499 billion on both tracks, and US$1.9 trillion with FTAAP, or almost two percent of global GDP. Interestingly, the biggest gains accrue when the two tracks are consolidated; in effect, this results from both China and the United States being included in the same agreement.

Regional aid for trade has been used as a means to foster regional integration and help regions achieve the goals of regional cooperation. For example, to this end the ASEAN Infrastructure Fund was created in 2012, and the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), with its secretariat at the ADB, has been highly successful in addressing key bottlenecks to trade in the Mekong region since its inception in 1992. It is important to note that these initiatives are often framed in the context of the need to reduce the costs of intra-regional interchange not as a means of raising intra-regional trade shares as a goal in itself but rather to attract production networks, which in turn usually have the effect of raising intra-regional trade, though not in all cases (intra-regional trade in ASEAN has only risen from 20 percent of total trade when AFTA was signed to about 25 percent today).

Lessons Learned

With multilateral liberalization negotiations on hold for the moment, regional economic cooperation has been the most dynamic element of commercial policy in the Asia-Pacific region and the world. Development assistance designed to facilitate regional economic integration is essential to ensuring that developing economies — in particular, low-income economies — can get the most out of this trend. We have noted above that regional aid for trade is an increasingly-important catalyst in this process, in the Asia-Pacific and the world. A recent survey of donors and recipients by the WTO, African Union, and United Nations Commission for Africa underscored that, while much progress needs to be made, aid for trade has had an important impact on regional integration. It has proven itself to be a very promising form of cost-effective aid.

As such, the aid for trade experience could offer some useful lessons for ecotech. While ecotech is fundamentally different from aid for trade, ex-post analysis of regional aid for trade projects offers, perhaps, some interesting lessons in terms of design of future projects and programs. Using information gleaned from for many “case stories” undertaken as a means of identifying the strengths and weaknesses of aid for trade projects to date, OECD-WTO (2013) comes to the following conclusions: (1) Projects need to stress the importance of ownership on the part of all stakeholders, including active “buy in” throughout the life of a project; (2) in terms of project design, there needs to be yardsticks for progress, and mechanisms to get back on track in case problems emerge; (3) projects need to have clear, realistic goals and there also needs to sufficient, built-in flexibility to manage unanticipated events; (4) while different projects have different goals, sustainability should be an important consideration for most projects, particularly in the economic infrastructure category; and (5) particularly for regional aid for trade projects designed to support production networks, it is important to engage the private sector and other non-government-affiliated partners.

The analysis in this chapter underscores many of these same issues. Given overlapping goals, aid for trade and ecotech have a good deal to learn from each other.

References

OECD, 2011. Aid Effectiveness 2005-2010: Progress in Implementing the Paris Declaration, available at: http://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/48742718.pdf .

OECD-WTO, 2011. Third Global Review of Aid for Trade 2011: Showing Results (Paris, OECD).

OECD-WTO, 2013. Aid for Trade at a Glance 2013 (Geneva, OECD-WTO, July).

Petri, Peter A., Michael G. Plummer, and Fan Zhai, 2012. The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: A Quantitative Assessment, Peterson Institute for International Economics, November.