CHAPTER 2 - APEC BEYOND 2020: WHAT LIES AHEAD?

CONTRIBUTED BY STEVEN WONG & EDUARDO PEDROSA

As APEC approaches 2020, relations among key member economies are marked by a degree of suspicion and hostility not seen in over half a century. To be sure, periods before this, even after APEC’s establishment in 1989, were not free of disputes. Disagreements, however, were managed and not escalated to full-on conflicts, and certainly did not take center stage at APEC Leaders’ Meetings.

These conflicts come at a critical juncture for the world economy. After a slow multi-year recovery from the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the green shoots of economic growth are now being weighed down by unprecedented policy risks and uncertainties. The multilateral rules-based trading system is also being further degraded in fundamental ways. Equally significant issues of inclusiveness, environmental sustainability and the onset of the digital and technological revolution are rising to the fore.

The overarching question that APEC now faces is how it can and should address them. Casting an APEC Post 2020 Vision was always going to be challenging, but recent developments may well be rendering it an impossible zero-sum exercise. APEC was established on the basis that positive-sum cooperation was essential to sustain the region’s economic dynamism and progress. The 1994 APEC Bogor Leaders’ Declaration summarized APEC’s Vision in the following manner:

“A year ago on Blake Island in Seattle, USA, we recognized that our diverse economies are becoming more interdependent and are moving toward a community of Asia-Pacific economies. We have issued a vision statement in which we pledged:

- to find cooperative solutions to the challenges of our rapidly changing regional and global economy;

- to support an expanding world economy and an open multilateral trading system;

- to continue to reduce barriers to trade and investment to enable goods, services and capital to flow freely among our economies;

- to ensure that our people share the benefits of economic growth, improve education and training, link our economies through advances in telecommunications and transportation, and use our resources sustainably.”

A year later, in 1995, they adopted the Osaka Action Agenda. Both the Vision and Agenda provided the raison d’etre for APEC’s approach and work. Today, the goals of cooperation, openness, removal of barriers and shared benefits as the primary means for achieving domestic goals are being set aside at an alarming pace.

APEC provides a platform for leaders, ministers, senior officials, and stakeholders to work together on forward-looking approaches to economic issues in a spirit of mutual respect. Its norms are based on openness, voluntarism, consensus-building, concerted actions along with a commitment to economic and technical cooperation and support for the multilateral system. These position APEC well as a dialogue mechanism.

As a precursor to APEC, the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC) remains committed to regional cooperation at the highest and deepest levels. Its assets include long understanding of the benefits and limits of regional cooperation, and the ability to provide frank assessments and inputs. In 2016, the PECC Standing Committee agreed on the APEC Post-2020 Vision as a signature project and convened a Task Force to carry it out. The Task Force carried out a survey of member committees with almost 300 responses and then developed a carefully worded Vision document that was adopted and shared among its members and other groups working on this issue. The PECC’s APEC Post 2020 Vision is the following:

“An Asia-Pacific community of openly interconnected, and innovative economies cooperating to deliver opportunity, prosperity and a sustainable future to all their peoples.”

This will be achieved by:

- Robust dialogue, stakeholder engagement, and effective cooperation that build trust and committed, confident relationships among member economies;

- Strategies and initiatives to remove barriers to full economic participation by all segments of society, including women, and people living in poverty, MSMEs, and remote and rural and indigenous communities;

- Committed long term policy initiatives that promote sustainability;

- Policies to harness the positive potential and address the disruptive impact of the digital economy and other innovative technologies;

- Structural reforms that drive growth by increasing productivity and incomes through open, well-functioning, transparent and competitive markets;

- Deeper and broader connectivity across borders, facilitated by high-quality, reliable, resilient, sustainable and broadly beneficial infrastructure and well-designed and coherent regulatory approaches, and including also a strong emphasis on supply chain and people-to-people connectivity;

- Intensified efforts to fully achieve the Bogor Goals of free and open trade and investment, with particular emphasis on components of the agenda where progress has been lagging;

- Strong APEC support for the multilateral trading system based on agreed values and norms reflected in updated multilateral rules, and including more effective settlement of disputes;

- High-quality trade, investment and economic partnerships among members, consistent with the values and norms of the multilateral trading system, and supporting dynamic responses to rapidly changing drivers of growth; and

- Concerted efforts in support of the eventual realization of a high-quality and comprehensive FTAAP to further advance regional economic integration.

Readers are asked to take note that the means of achieving the Vision are as, if not more, important than the Vision itself; they are not mere ancillary bullet points. This chapter uses the results of PECC’s Annual Survey of the regional policy community to elaborate on the PECC Vision and draws on related work that provides some sense of the potential benefits of achieving that vision and the costs of failure.

APEC’s Strategic Value

APEC is the preeminent inter-governmental institution for dialogue encompassing economies from both sides of the Pacific Ocean. The fact that it is structured for dialogue and voluntary action rather than formal commitments may be considered a drawback by some but providing an overarching sense of common purpose for cooperation is not one of them. Member economies vary greatly in size, capabilities and political and economic organization and cultures. As a result, they do not always have completely compatible sets of interests and worldviews, and hence there have been trade and investment frictions. By and large, these have been managed through bilateral and plurilateral mechanisms. Some critics of APEC have often called it a ‘talk shop’ without considering the tangible negative implications when parties pull back and are no longer prepared to talk. It can be said that it is precisely this lack of a semblance of common purpose, engagement and constrained behavior that today is palpably contributing to the great unease in financial markets, private companies and the policy and academic communities. APEC’s strategic value does not lie in the absence of disagreements among member economies but the political commitment to resolve these and future disagreements within the framework of a greater collective.

APEC is strategic in another way. In the early 1990s, APEC members chose to open and liberalize their markets through their commitments in APEC. For APEC members who had not yet joined the WTO (such as Vietnam, China, and Russia), APEC membership was seen as vital to deepening their understanding of the disciplines involved with international rules and gaining domestic political support for reforms. With momentum for the WTO’s Doha Development Round slowing to a virtual standstill, APEC became a useful platform for like-minded members to continue to open their economies and deepen integration through compatible rulemaking. While the proposal for a 21-member inclusive Free Trade Area for the Asia Pacific (FTAAP) has not gained traction, the conclusion of the smaller Comprehensive and Progressive Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP), with open accession provisions so other member economies can join, provides a strong rules-based pathway to achieving the goals of APEC.

Does APEC still matter?

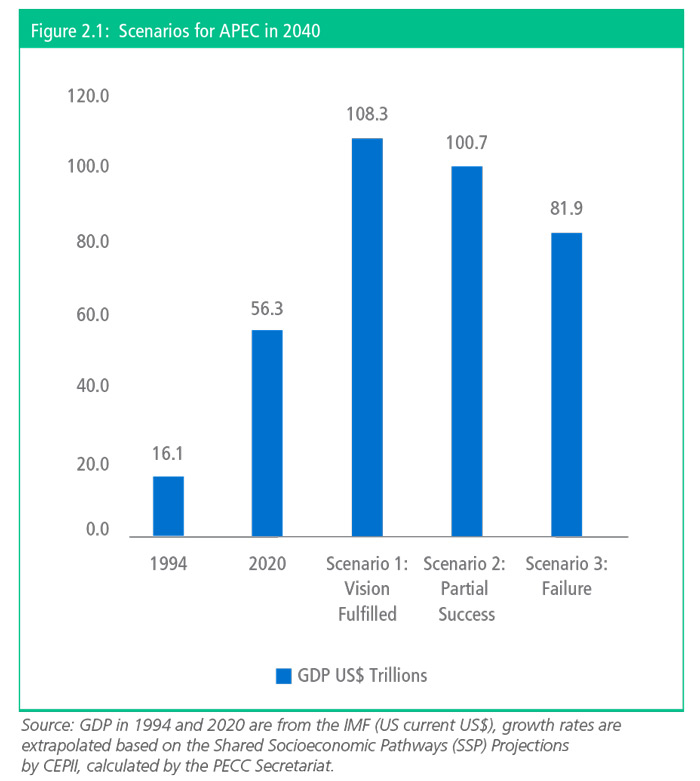

The rapid growth of APEC’s 21 member economies means that it is a vastly greater prize to be treasured, defended and enhanced more than at any time in the past. In 1994, when the Bogor Goals were announced, the combined GDP of all current APEC members was about $16 trillion (current US$) or under 50 percent of the world economy. By growing at an average annualized 4.9 percent over the past quarter of a century, APEC GDP will surpass US$56 trillion or more than 60 percent of the world in 2020. It is crucial, however, to note important changes in characteristics.

APEC economies have been able to turn in above-average growth performances because of strong contributions from trade in goods and services. In 2020, trade will be seven times larger than in 1989. Policy actions aimed at restricting trade, investment and technology flows therefore go directly to the heart of the engine driving growth of the region. Undeniably, trade and investment liberalization have been slow and uneven in member economies. Market access continues to be hampered by new non-tariff (and now tariff) measures, while restrictions on investment and intellectual property protection create unlevel playing fields and distort flows. PECC’s Vision for APEC calls for robust dialogue, stakeholder engagement, and effective cooperation to address the unfinished agenda of the Bogor goals and promote open, transparent and competitive markets.

If APEC economies were already recognized to be ‘interdependent’ in 1994, they have become infinitely more so in 2020 and there are strong indications that these trends will continue. Indicators of global and regional value chains (GVCs & RVCs), broadly defined as the percentage of trade crossing borders more than once, have generally risen. Economies are investing a great deal in physical infrastructure and promoting connectivity within and outside their borders. At the same time, digital technologies have meant that parts and product outsourcing has now evolved to become complex value chains of goods and services. Driven by productivity gains, these have greatly lifted welfare in ways that are not always appreciated or fully measurable, and they are continuing to transform economies going forward. Both trends critically require sound and coherent policies and regulatory approaches if member economies are to fully benefit from them.

The ultimate prize for APEC member economies lies not merely in its members collective economic scale but the ability to improve the living standards of its citizens. Per capita incomes in the region have risen 75 percent in the three decades to 2020, lifting millions out of poverty, creating large and vibrant middle classes whose consumption helps sustain growth, contribute to political stability and, through cross-border travel, spread incomes and wealth. On the darker side, there are those who have not been able to fully participate in growth, feel marginalized and become politically discontented. Rather than turning inwards, APEC economies have clearly to emphasize inclusiveness and quality growth to a much greater degree and not just pursue growth at any and all costs, both domestically and regionally.

The issue of sustainability is one that now urgently requires collective public goods to manage the negative economic and social externalities of economic growth. Sustainability covers many inter-related aspects but chief among them is the impact on the environment (or biosphere). Technology holds great promise and is beginning to take hold in some areas, such as in renewable energy but emissions of greenhouse gases, deforestation, loss of biodiversity and natural habitat, wastes, especially of plastics, are taking a visceral toll on natural and human populations, especially those of lesser developed economies.

Costs of fragmentation

Any attempt at modeling the future of APEC economies is, by its nature, illustrative and fails to take into account the many economic interdependencies and political uncertainties, which are often selfreinforcing. In looking ahead to 2040, we use the estimates of the Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (CEPII)1, Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) to see the material impact on peoples’ lives and what might be needed to achieve them. The SSP is intended for CEPII’s own purposes but is broadly in line with APEC’s aspirations and include some of the key concerns that future growth in the region be more sustainable and inclusive as well as bolster support for multilateral institutions.

- SSP Scenario 1: (in our words: Vision Fulfilled). This is a world making relatively good progress towards sustainability, with efforts to achieve development goals, while reducing resource intensity and fossil fuel dependency. This world is characterized by an open, globalized economy, with relatively rapid technological change directed toward environmentally friendly processes, including clean energy technologies and yield-enhancing technologies for land. Consumption is oriented towards low material growth and energy intensity.

- SSP Scenario 2: (in our words: Partial Success). APEC economies make some progress on elements of the vision. This is based on SSP2 Middle of the Road. In this world, trends typical of recent decades continue, with some progress towards achieving development goals, reductions in resource and energy intensity at historic rates, and slowly decreasing fossil fuel dependency. Most economies are politically stable with partially functioning and globally connected markets. A limited number of comparatively weak global institutions exist. Per-capita income levels grow at a medium pace on the global average, with slowly converging income levels between developing and industrialized economies.

- SSP Scenario 3: (in our words: Failure). APEC economies either fail to adopt a vision similar to that articulated here or are unable to make progress along the way. This is based on SSP3 Fragmentation. The world is separated into regions characterized by extreme poverty, pockets of moderate wealth and a bulk of economies that struggle to maintain living standards. Regional economic blocs have re-emerged with little coordination between them. This is a world failing to achieve global development goals, and with little progress in reducing resource intensity, fossil fuel dependency, or addressing local environmental concerns such as air pollution. The world has de-globalized, and international trade, including energy resource and agricultural markets, is being severely restricted. Little international cooperation and low investments in technology development and education slow down economic growth in high-, middle-, and low-income regions. Governance and institutions show weakness and a lack of cooperation and consensus; effective leadership and capacities for problem-solving are lacking.

As shown in Figure 2.1, the difference between fulfillment of the vision and partial success is significantly smaller than between failure and partial success. In other words, even slow progress towards the goals is preferable than a reversal. Annualized growth in Scenario 1 is 3.3 percent for the APEC region, 1.6 percentage points slower than the growth from 1994 to 2020. Under Scenario 2, annualized growth for APEC members would be 0.3 percentage points lower than under Scenario 1 at 3.0 percent while Scenario 3 would be the lowest at 1.9 percent.

These examples do not capture some of significant policy developments that have already taken place such as the entry into force of the CPTPP, the recently concluded Japan-US minitrade deal or the ongoing Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations. These are potentially significant. Earlier modelling work suggests that the impact of the TPP that included the US would increase baseline GDP for APEC members by 0.4 percent and an RCEP by 0.9 percent. If an FTAAP were to be achieved based on the TPP template it would increase baseline regional GDP by 4.3 percent by 2025.

Vision Beyond Trade?

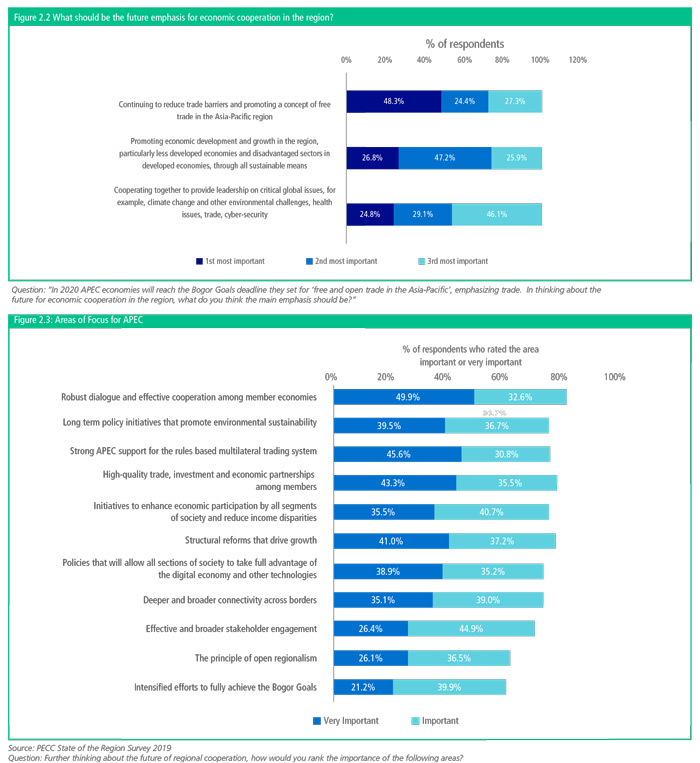

The PECC Task Force on the APEC 2020 Vision sought to gain a better understanding of the Vision by surveying its stakeholders in 2018 (almost 300 responses) and in the PECC Survey on the State of the Region 2019 (627 responses). The results of the latter are reported below and strongly reinforce the central themes of the PECC Vision for APEC.

As shown in Figure 2.2, 48.3 percent of the regional policy community believes that “continuing to reduce trade barriers and promoting a concept of free trade in the Asia-Pacific region” is the most important emphasis for regional cooperation. This compares with 27 percent who placed “promoting economic development and growth in the region, particularly less developed economies and disadvantaged sectors in developed economies, through all sustainable means” as APEC’s number one priority and 25 percent for “cooperating together to provide leadership on critical global issues, for example, climate change and other environmental challenges, health issues, trade, cyber-security”.

Robust Dialogue Critical for APEC

Moving on to specific areas of focus, respondents to PECC Survey on the State of the Region 2019 were asked to rank each of the 10 areas of focus seen as important to achieving the post-2020 vision for APEC.

As shown in Figure 2.3, 50 percent of respondents from the regional policy community ranked “Robust dialogue and effective cooperation among member economies” as very important.

Figure 2.3 displays the different areas of works in order of weighted scores. However, it is also striking to look at the percentage of respondents who selected areas as ‘very important’. Listing areas in that way the top 5 were:

- Robust dialogue and effective cooperation among member economies

- Strong APEC support for the rules-based multilateral trading system

- High-quality trade, investment and economic partnerships among members

- Structural reforms that drive growth

- Long term policy initiatives that promote environmental sustainability

Given APEC’s traditional focus areas on trade, the results were somewhat surprising. While APEC’s traditional modality of robust dialogue was seen as something critical to its future, the survey indicated a desire for APEC to undertake more work on sustainability followed by traditional areas.

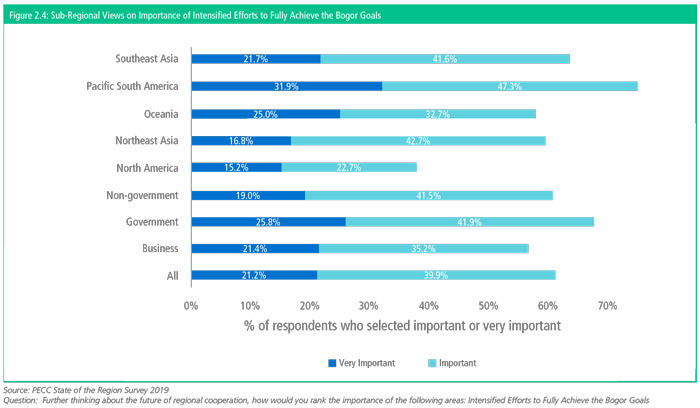

Achievement of Bogor Goals

Given the responses to shown in Figure 2.3, it is somewhat surprising that ‘intensified efforts to fully achieve the Bogor Goals’ (of free and open trade and investment in APEC by 2020) ranked the lowest amongst the areas of focus. This is perhaps symptomatic of the present reality of trade conflicts in the region and, to some degree, a discouragement effect. Deeper analysis of the survey results shown in Figure 2.4 indicate differences within the regional policy community. For example, 32 percent of respondents from South America rated Bogor as very important compared to only 17 percent of Northeast Asians. In any case, efforts to achieve the Bogor goals are still regarded as important but perhaps to a lesser extent than other activities.

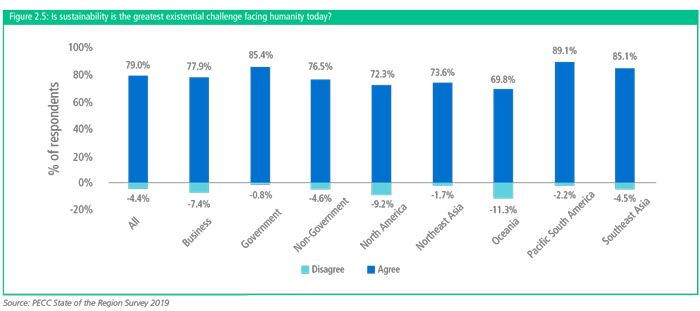

Sustainability

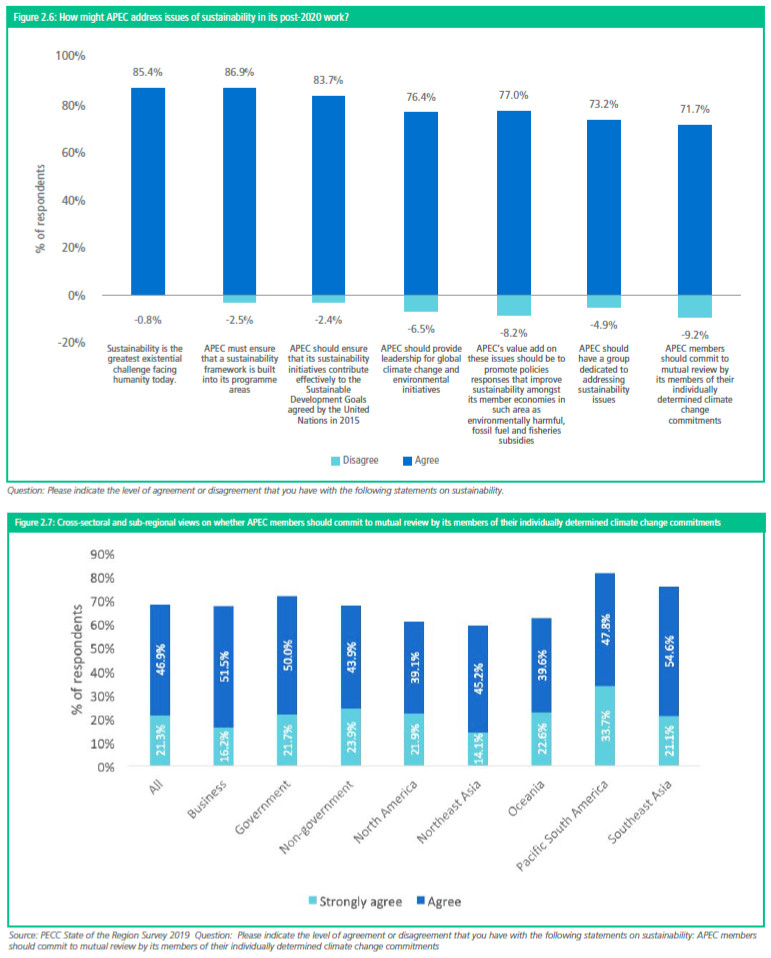

As shown in Figure 2.3, there was a high degree of support among the regional policy community for APEC focusing more on sustainability issues as part of its post 2020 work. Sustainability and inclusiveness are already highlighted as necessary features of economic growth in the APEC Strategy for Strengthening Quality Growth, endorsed by Leaders in 2015 but more needs to be done in the coming two decades.

There was broad agreement across the Asia-Pacific that sustainability is the greatest existential challenge facing humanity today but with some variance among sub-regions. Respondents from Pacific South America were in the strongest agreement while those from Oceania registered more disagreement, along with North America. Amongst the different sectors, government respondents agree the most strongly while business sector were in the weakest agreement.

To gauge the level of agreement around the Asia-Pacific policy community on some possible key concepts and ways in which APEC might address sustainability issues, survey respondents were asked to indicate their levels of agreement with a number of statements. As shown in Figure 2.5, there was broad agreement that APEC should have a sustainability framework and contribute to the achievement of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

As shown in Figure 2.7, there was overall agreement on the idea that APEC members should commit to mutual review by members of their individually determined climate change commitments but there was considerable variance among sub-regions on their agreement. Looking only at percentages of those who strongly agreed. the highest level of support came from Pacific South America with 34 percent but only 14 percent of those from Northeast Asia agreed.

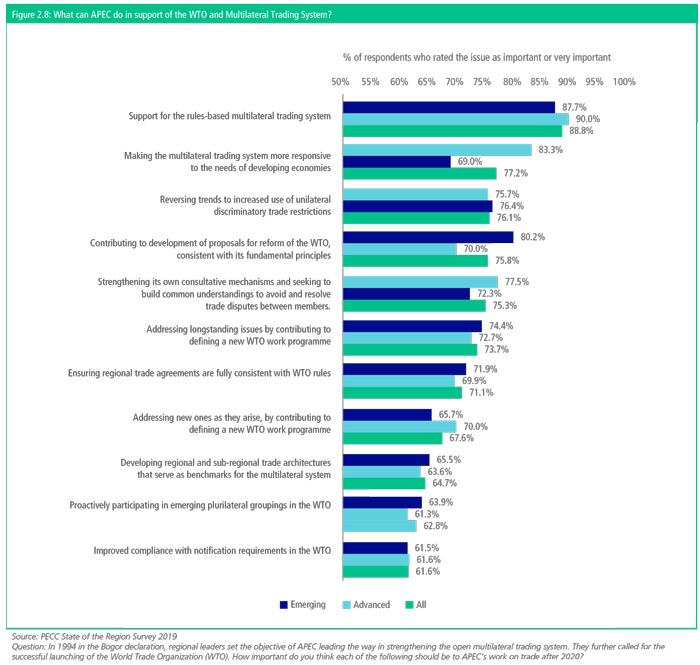

Support for the WTO and Multilateral Trading System

As shown in Figure 2.3, support for the rules-based multilateral trading system ranked third in the areas of focus for APEC work in its post-2020 vision. Indeed, support for the rules-based system has been at the heart of APEC since its very founding and was part of its rationale as argued by former Australian Bob Hawke (see chapter 1). Figure 2.8 shows the survey results for respondents from advanced economies and emerging to demonstrate that with the exception of “Making the multilateral trading system more responsive to the needs of developing economies” there were high levels of convergence on the rankings given to the various actions suggested in the PECC survey. Even then, it is not that respondents did not consider it a low priority, with 69 percent of respondents from advanced economies ranking it as either important or very important, it was just slightly less important for them than for respondents from emerging economies.

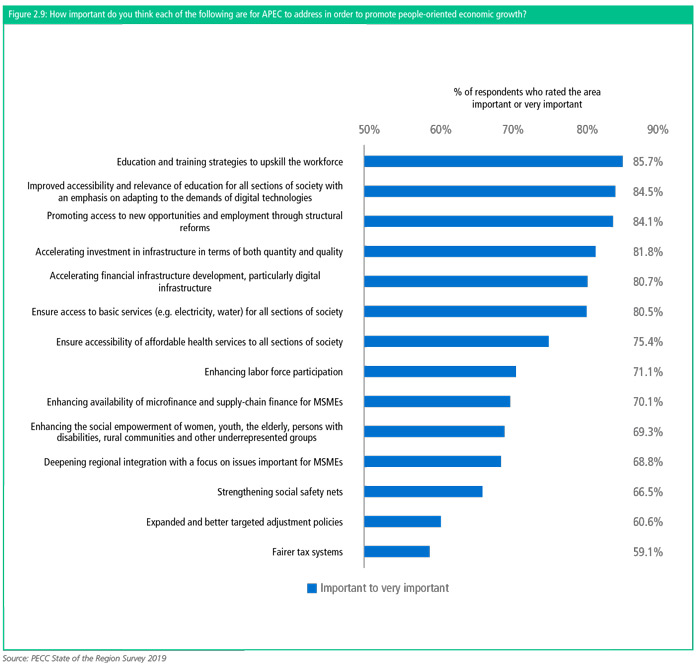

Inclusion

Initiatives to enhance economic participation by all segments of society and reduce income disparities ranked fifth among the focus areas for APEC’s post-2020 work. Survey respondents were asked to rank a variety of initiatives that APEC could undertake to promote more people-oriented growth in the region. As shown in Figure 2.9, the top 5 were related to education, employment and opportunities through structural reforms and infrastructure.

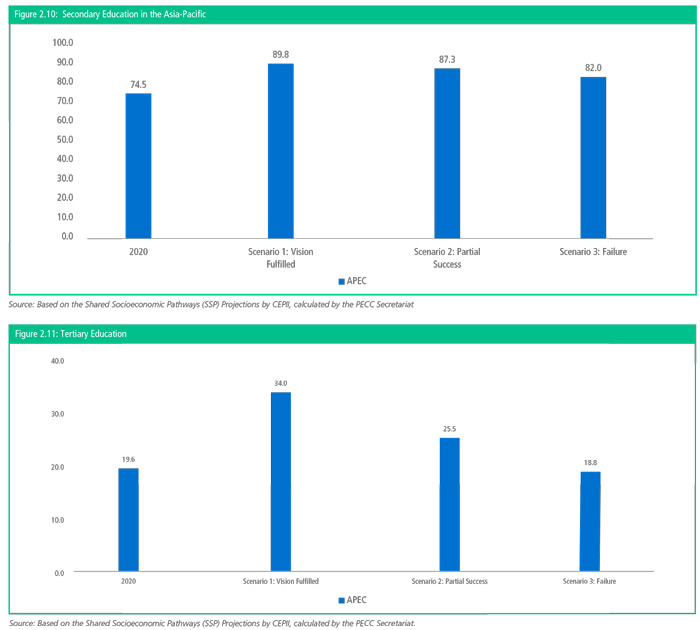

Education and training, in particular, is fundamental to how APEC economies perform in the coming decades, this is confirmed by the CEPII study referenced earlier. Today, around 1.49 billion people in the APEC region have secondary education. To achieve the growth rates for Scenario 1, the percentage of the workforce with secondary education needs to have increased from about 75 percent to 90 percent by 2040. Under Scenario 2 the assumption is that 87 percent of the workforce has secondary education while under Scenario 3 just 82 percent. The magnitude of the challenge should not be underestimated, this involves providing secondary education to an additional 250 million people over the next 20 years under Scenario 1.

Tertiary Education

An even bigger challenge given the rapid changes taking place to the nature of work is in the ability of education systems to deliver tertiary and lifelong education. As seen in Figure 2.10, approximately 20 percent of the working-age population has some form of tertiary education. To achieve the growth envisioned under Scenario 1, that will need to significantly increase to about 34 percent of the working-age population. This is an increase of tertiary education for 268 million people. Under Scenario 2, only 25 percent of the population is assumed to have some form of tertiary education while under Scenario 3 the percentage of the workingage population with tertiary education actually goes down. As a point of reference, today, about 37 percent of Australia’s workingage population has some tertiary education while less than 10 percent of Vietnam. The potential for digital delivery of education is enormous, for example, the Topica EdTech Group is delivering online tertiary education to thousands of students in Vietnam at a fraction of the cost.

Structural Reforms

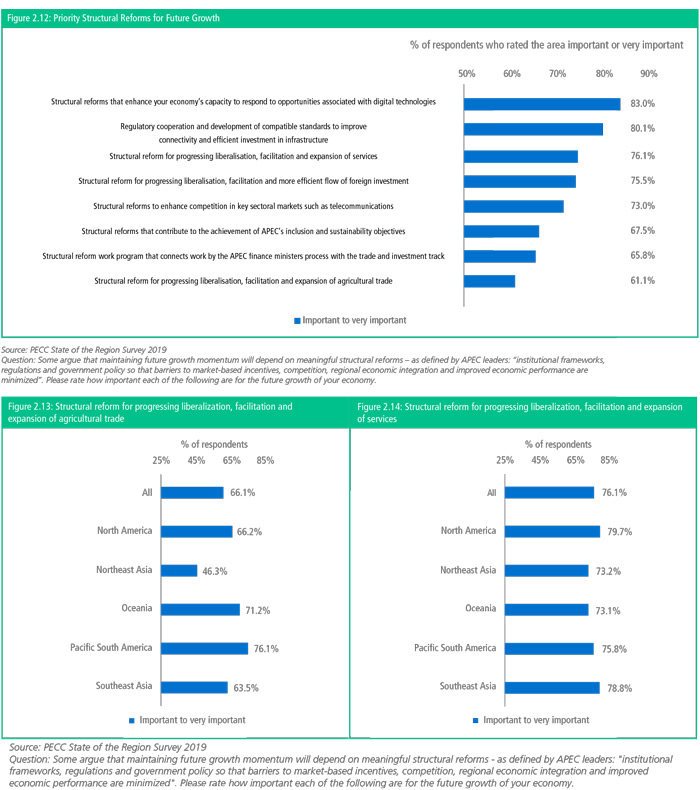

Structural reforms have already been mentioned as a priority with respect to promoting people-oriented growth. Survey respondents were asked to rank the importance of different types of reforms in a number of different sectors in connection with how important they would be to the future growth of their economies.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the top areas of focus were reforms to enhance responsiveness to opportunities associated with digital technologies. This was followed by reforms to improve connectivity and the efficiency of infrastructure and in the services sectors.

Structural Reforms and the Trade Agenda

The PECC report on the post-2020 vision argued that APEC members should explore the potential for its work on structural reform to contribute to achieving its goal in areas where significant barriers remain – agriculture and services trade most notably. As seen in Figure 2.12, structural reform for advancing liberalisation, facilitation and expansion of services were ranked highly by the regional policy community as being important for the future growth, structural reforms were not as important in agricultural trade. Figures 2.13 and 2.14 below shows the breakdown of responses by sub-region on these elements.

While there was little variation among sub-regions on how they saw the importance of structural reforms for services, Northeast Asian respondents evaluated the importance of structural reforms for liberalization of agricultural trade was much below other subregions.

BOX 1 INTERVIEW WITH ANTHONY VIEL, CEO FOR DELOITTE CANADA AND CHILE, AND RICARDO BRIGGS, REGIONAL MANAGING PARTNER FOR DELOITTE CHILE

What is the digital society, and what does it mean for our economies and our businesses? We sat down with leaders Anthony Viel, CEO for Deloitte Canada and Chile, and Ricardo Briggs, Regional Managing Partner for Deloitte Chile, to learn how digital innovations are impacting society at home and abroad.

Q: Why is the digital society so transformative for economies and societies?

AV: Digital is not about digitizing the analog but rather the new normal for redefining the rules of business, government and societies. Unprecedented levels of connectivity, computational speed and data have enabled a future never seen before.

Digital innovations are reshaping our society—and economy—at an unprecedented speed. New information and communication technologies have infiltrated every aspect of our lives, and the expanding role of data has become top of mind not only for business and government, but for citizens as well.

In Canada, for example, growth in the digital economy has outpaced any other sector over the last decade, to the point where in 2017 (the most recent government data) the digital economy was worth $109.7 billion, or around 5.5% of the overall economy, and employed nearly 900,000 people. This is a revolutionary shift in how our economy works, and all businesses in all industries need to understand these changes in order to capitalize on the immense opportunity it represents.

Ricardo: In Chile, consumers have become a key contributor to the country's digital growth. The rate of adoption for internetconnected mobile devices multiplied by eight from 2010 to 2016—that fastest growth among OECD countries. Four out of five Chilean adults already are now connected to the internet. And as a result, the Chilean e-commerce market has been growing at 24.5%, from about USD 447 million in 2008 to USD 4 billion in 2017.

But while everyone wants to be a part of this process, businesses and government leaders lack a common understanding about how to manage the transformation. The result has often been piecemeal initiatives that lead to missed opportunities, sluggish performance, and false starts. Properly managed, digital society can create value for business, transform how we interact with our governments, and democratize access to skills and capabilities. But capturing these benefits will require a more strategic approach than we’ve had so far. There is tremendous opportunity if only we are able to seize the moment.

Q: Are there particular aspects of the digital society that present the greatest opportunities? What are you seeing emerge in the marketplace?

Ricardo: At Deloitte, we believe that artificial intelligence (AI) will be one of the most transformative technologies of our time. It has touched nearly every industry and sector, and it has the potential to drive exponential change in the near future.

According to the AI Readiness study during the first half of 2019, 78% of Chilean companies have not incorporated AI technologies in their processes, products and services. 14% are in insufficient degrees of use and only 8% have incorporated it in a generalized way.

Recognizing the potential of the technology, we are investing to make AI expertise a core element of our business. Over the last year we launched a new AI consulting practice called OMNIA AI. This is the first AI practice of its magnitude launched by any professional services firm in Canada or Chile. OMNIA focuses on one common goal: helping drive adoption of cutting-edge AI technologies.

AV: That’s right. Over the last year, our firm launched a research series looking at the challenges to AI adoption in Canada. We found that 71% of Canadian businesses still do not make use of AI, even though more than half of these non-adopters agree that Canada needs to be a global leader in the field.

While these results could be discouraging, we also see them as representing tremendous opportunity. We have used our research to urge leaders to accelerate AI adoption—from initial deployment all the way to using AI applications at scale. And we constructed a roadmap for government and businesses to follow that can establish Canada as a global leader in this field.

These investments into our business and our countries are us walking the walk—our big bet on AI as one of the greatest opportunities of the digital society.

Q: What challenges stand in the way?

AV: The focus of our leaders too often becomes stuck on risks rather than opportunities, and that threatens to hold us back. Deloitte has found that only 11% of Canadian companies and 4% of Chilean companies can be considered truly courageous— with a growth mindset, an openness to calculated risks, and a willingness to challenge the status quo.

The problem is that a more courageous mindset is a key ingredient to success in the digital economy. Businesses need to do more to collect and make use of quality data, the primary enabler of digital technologies. We need to do more to educate the public and each other on what these technologies are and how we can use them. And we all need to do more to earn and deserve the trust of citizens who have legitimate concerns about how these technologies affect their lives. Only 4% of Canadians today are confident explaining what AI is and how it works. This lack of understanding of digital technologies and how they already impact our lives threatens to undermine our transition to the digital society and the benefits it can bring.

Q: What role do you see for regional cooperation to harness the digital society’s full potential? Where should APEC prioritize as part of a post-2020 vision?

Ricardo: In recent years, the Asia-Pacific has enjoyed a fundamental shift towards greater regional integration, with coordinated trade, finance, and transport. But at the same time, we live in an increasingly insular world, where trade barriers and preferential policies threaten to limit the free flow of people and ideas. If we are to realize the full potential of a digital society, the process now demands new regional agreements with the objective of pulling up the small and emerging economies by sharing best practices and knowledge.

AV: The best way to cope with the future is to create it. APEC can play a key role as a convener and an advocate in building toward a more open world. Through collaboration, we can align standards and practices, build enabling infrastructure, and capture the shared benefits of new digital technologies.

Towards a Unified Asia-Pacific Digital Market

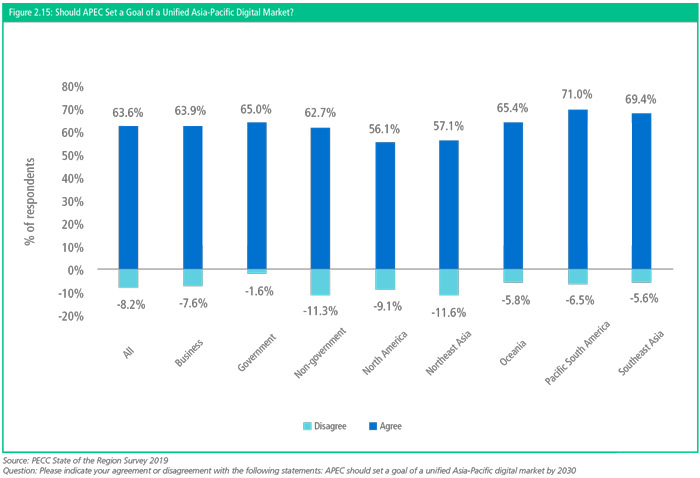

PECC’s task force on a post-2020 vision for APEC suggested that one way to advance the 2017 APEC Internet and Digital Economy Roadmap that set out an extensive and formidable agenda of issues is to prioritise urgent development of understandings and consensus leading to development of a unified Asia-Pacific digital market by 2030.

As shown in Figure 2.15 there is broad support for the idea of that “APEC should set goal of a unified Asia-Pacific digital market by 2030” as part of its post-2020 agenda. This was a view shared among the various sub-regions of the Asia-Pacific as well as different stakeholder groups. The fact that support is least evident (and disagreement strongest) among Northeast Asia and North America member economies may be indicative of the challenges that need to be faced.

The APEC Internet and Digital Economy Roadmap (2017) sets out an extensive and formidable agenda of issues in APEC, including:

- Development of digital infrastructure;

- Promotion of inter-operability

- Achievement of universal broadband access;

- Development of holistic government policy frameworks for the Internet and Digital Economy;

- Promoting coherence and cooperation of regulatory approaches affecting the Internet and Digital Economy;

- Promoting innovation and adoption of enabling technologies and services;

- Enhancing trust and security in the use of information and communications technologies(ICTs);

- Facilitating the free flow of information and data for the development of the Internet and Digital Economy, while respecting applicable domestic laws and regulations;

- Enhancing inclusiveness of the Internet and Digital Economy.

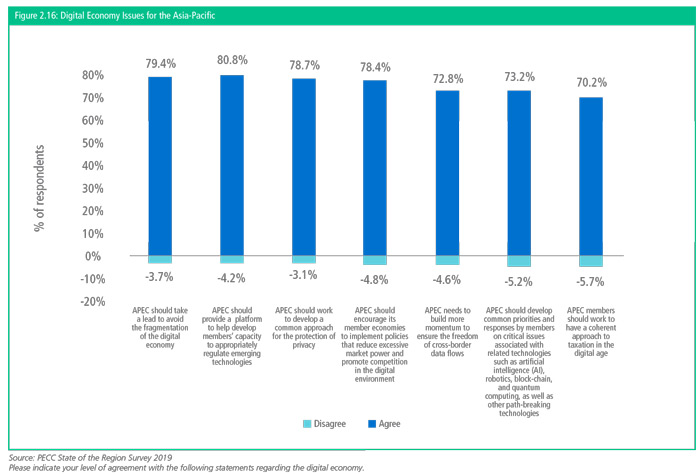

There is remarkable agreement amongst the expert policy community about difficult policy issues at the regional and multilateral level. As shown in Figure 2.14, there is little disagreement with statements on the importance of APEC addressing these issues.

As shown in Figure 2.16 there was broad agreement among the regional policy community on specific issues that APEC could address.

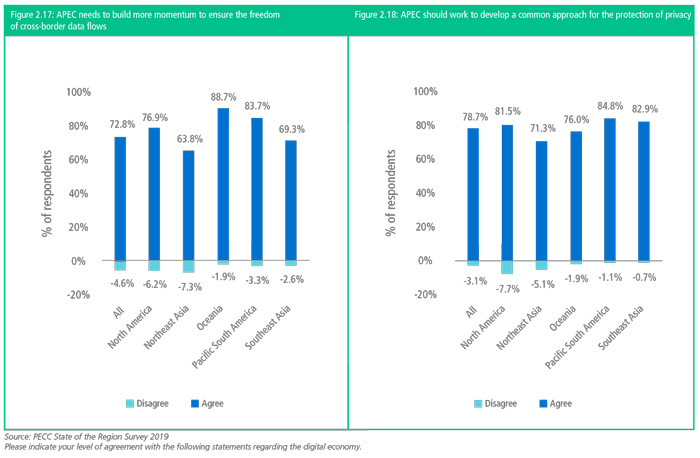

Cross Border Data Flows and Privacy Protection

Even on fairly contentious issues where APEC economies are known to have different approaches, as shown in Figures 2.17 and 2.18 there was very strong support for more APEC work to ensure the freedom of cross border data flows as well as develop a common approach for the protection of privacy. There were differences among sub-regions, for example, Northeast Asian and Southeast Asian respondents were slightly less enthusiastic about the need to build more momentum on cross border data flows while there were slightly more supportive of idea of developing a common approach for the protection of privacy.

What these survey results indicates is at least a very strong interest in the desire to explore the potential for cooperation and common approaches to these critical issues over the coming years.

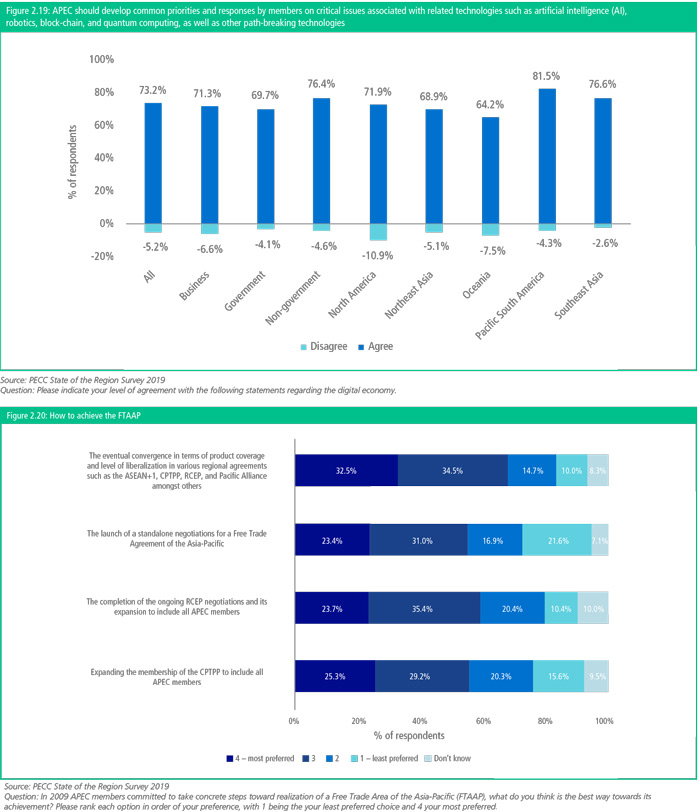

Even on issues that have not yet been discussed by officials, there was a strong desire by the policy community to see APEC develop common priorities and responses on critical issues related to them such as artificial intelligence robotics and blockchain. In other words, APEC’s traditional role as an incubator should not only continue but needs to be strengthened in the face of these very rapidly changing technologies.

Pathways to a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific

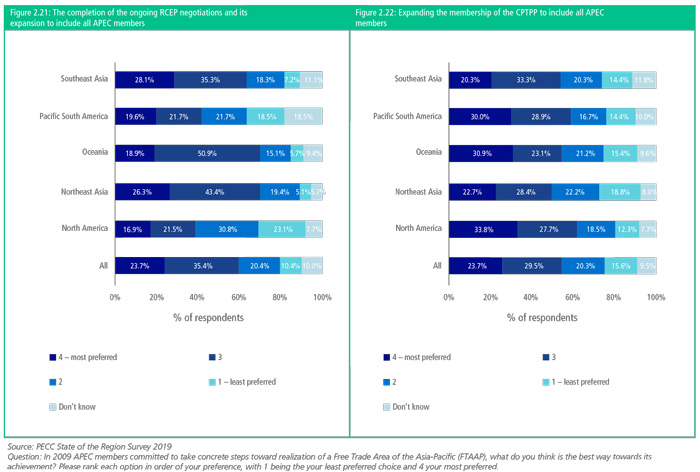

A Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) has been an aspirational goal for APEC since leaders agreed in 2009 to its realization by developing and building on ongoing regional undertakings. A decade since then, one of the pathways has since been completed – the CPTPP -- and the RCEP negotiations are ongoing. As shown in Figure 2.20, the regional policy community’s preference is for the eventual convergence of the different pathways.

There were some significant differences among sub-regions on their preferences. As shown in Figures 2.21 and 2.22, Northeast Asian and Southeast Asian respondents tended to prefer “The completion of the ongoing RCEP negotiations and its expansion to include all APEC members” while North Americans tended to prefer the expansion of the CPTPP.

Priority issues for Asia-Pacific Trade Agreements

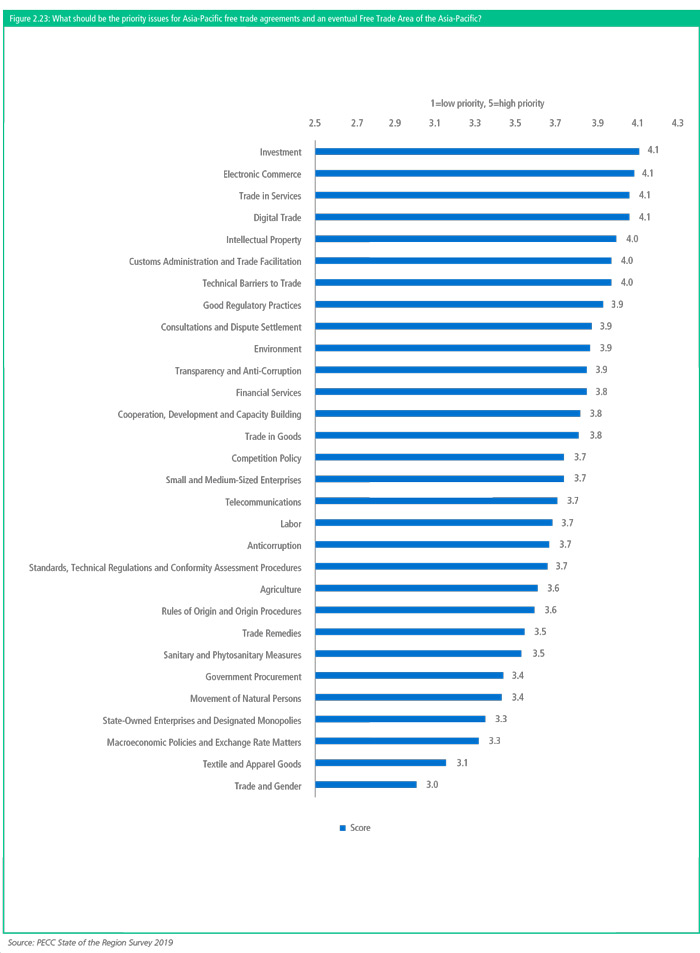

As discussed above, the preferred way to achieve an FTAAP is the eventual convergence of existing trade agreements. However, there are some significant differences not only in their levels of liberalization but also in the issues they address. Respondents to PECC’s survey were asked to rate issues that have appeared as chapters in a variety of Asia-Pacific trade agreements in terms of their priority.

Interestingly the issues that were most highly ranked tended to be newer issues – investment, electronic commerce, trade in services, digital trade, & intellectual property.

Meeting the Bogor Goals

As shown in Figure 2.24 and 2.25 there was a consistent view across different stakeholder groups that neither industrialized nor developing APEC members have met the Bogor Goals. Respondents from government tended to the most positive with their assessments even though on balance they tended to think that the goals have not been met by either group while respondents from the non-government sector tended to be the most negative.

However, in spite of this assessment, respondents also had a very positive view towards APEC. As shown in Figure 2.26, 76 percent of respondents agreed that APEC is as important or more important today compared to 1989 when it was created. This positive evaluation of APEC has not been consistent over the history of PECC’s State of the Region survey. In 2007, attitudes towards APEC can best be characterized as ambivalent with 47 percent having a negative view and 48 percent a positive view. Over the course of the past 12 years, the percentage of those with negative attitudes towards APEC steadily declined while those with positive views increased.

BOX 2 NEXT GENERATION VIEWS ON APEC BEYOND 2020

Since 2009 PECC has included youth delegates through a next generation program to its General Meetings, Participants include students at the graduate and post-graduate levels. Former participants in these programs were invited to share their views on the vision for APEC beyond 2020. By the time this vision will be assessed, hopefully some of those who participated in those programs might be responsible for its achievement. A selection of those views is below.

Corey Wallace, New Zealand

He was a Next Generation Delegate to the PECC General Meeting held in Tokyo, 2010 he is currently a postdoctoral Fellow in the Graduate School of East Asian Affairs, Freie Universität Berlin

Societies have not adequately adapted to climate change and there is little thinking about the impact of future technological disruption on societal norms and social structures. A new ‘social contract’ is required in terms of what is expected of youth in terms of work and their career development, how they will contribute to society in terms of taxation and participate in civil society, and what assurances in terms of social security they will receive as the nature of work and society changes. Indeed, the two more concrete issues of climate change and technological innovation are tightly bound up with the challenge of the need for a new social contract for all societies in the region.

The impact of climate change on both developing and developed societies in the region has only just started to be discussed. For everyone, it will mean changes in the patterns of consumption and energy use. For some societies, however, especially in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, climate change might even mean the wholesale relocation of populations.

Technological change will radically affect the nature of work. Among the younger generation of workers and entrepreneurs we are seeing much more diverse, unstable working styles. This is not always purely by choice. We are only on the leading edge of technology change in areas such as Artificial Intelligence, robotics, additive manufacturing, autonomous vehicles, quantum computing, health, genetics and restorative/ regenerative medicine that will change the way everyone lives and works. The opportunities for society and for everyone to enjoy a wealthier, convenient lifestyle are certainly apparent. Life might become more convenient for many people, but social mobility might essentially come to an end except for a select few.

I think APEC can only do so much on the climate change front given other international institutions are struggling to address this problem. But, as technological change deepens alongside increased trade and investment flows within the region, APEC could lead a much more involved discussion about not only income equality or equity, but also intergenerational wealth equality or equity as people start to live much longer.

There is in many cases active resistance to the need for radical changes in taxation and social security in order to ensure younger generations can benefit from the economic growth associated with regional economic integration and any future strengthening of APEC. My sense is a failure to address these issues could result in significant polarization within and between societies, putting a cap on further economic integration, which could undermine the APEC project of an integrated Asia-Pacific.

Yung Woong Koh, Korea

He was the Third Prize Winner of the PECC Essay Competition in 2015 and a Next Generation Delegation to the PECC General Meeting in Manila, 2015 now works for the National Assembly Budget Office, Korea

The greatest challenge to APEC today is the political leadership in APEC's member economies such as the US-China trade conflict as well as frictions between Japan and my own native Korea. We should still strive for a global trade agreement via the WTO, or if not, at least large regional ones that provide some measure of lessening uncertainty between trade partners.

I also believe that APEC should focus more on developing the potential of the digital economy in developing economies through market-based means. I believe that as much as APEC member economies’ governments are supposed to deliver public goods such as infrastructure, there need to be more fiscally and financially sustainable ways of fueling the growth for infrastructure.

Mr. Marcelo Valverde, Peru

He was the First Prize for the PECC Essay Competition in 2015 and was a Next Generation Delegation to the PECC General Meetings in 2014 and 2015 he is now a Trade Officer with the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Tourism in Peru

APEC is a dynamic forum that has many achievements as described in the APEC’s Bogor Goals Progress Report 2018, however, it should be noted that Bogor Goals are not fully accomplished and with less than one year to its deadline, it is unlikely to happen.

In this context, I believe that APEC could continue with a trade vision in the next years, but with concrete steps to the realization of the FTAAP and the inclusion of private sector, especially MSMEs. Even in the context where there are many next generation topics such as digital economy, environment among others, APEC economies need to clearly define how they could address them, while looking to deepen economic integration.

Dr Juita Mohamad, Malaysia

She was a Next Generation Delegate to the PECC General Meeting held in Tokyo, 2010 and is now a Fellow with the Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia.

India has been interested in joining APEC long before 2015. Even though India is one of the fastest developing economies in the region, members of APEC are divided about its membership. India’s entry into APEC has been blocked due to different reasons, namely its unfair treatment of foreign direct investments and its perceived inability to carry out steady economic reforms.

India in APEC can be beneficial for all members in terms of market access. Market access beyond national boundaries is a critical factor in strengthening export performance. For APEC members, greater integration with India would translate into an alternative source of intermediary goods, especially manufactured goods. India as a new trade partner can serve as a new and sustainable engine of growth for the region reducing dependence on economies that are now slowing.

More importantly, trade has been successful in pulling sections of population out of poverty, by creating jobs and opportunities for a given economy. If the region is serious about narrowing developmental gaps between member economies, a more inclusive approach is to include India in the pathway to membership, by working on areas of cooperation to prepare India to be a part of the APEC community. Instead of excluding those that are different, cooperation and exchange of views and practices is vital to break the ice.

Conclusion

Contrary to those who would write it off, APEC as an institution is still regarded by its key stakeholders as highly relevant in the coming decades. In contrast to the 1994 Bogor Goals, however, APEC’s remit is now clearly broader than when the Vision was first conceived. Within the trade and investment agenda, investment and services liberalization and e-commerce and digital trade harmonization are now central areas of work. Issues of inclusiveness and sustainability have moved from being ancillary to become important joint goals to be achieved. Within these, the human resource development and structural reforms to capitalize on emerging digital technologies and improve connectivity and investment in infrastructure are critical underlying subthemes.

APEC’s primary strategic value lies in its being an overarching platform for discussion and cooperation rather than negotiating. If there is one key to PECC’s Vision for APEC lies in the term ‘robust dialogue’. It is clear that APEC needs frank, realistic and rational discussions to inject fresh political commitment into what will become its core agenda. This is critical to dispel any doubts that APEC does not have the interest and wherewithal to perform this role.