Chapter 2 - Can RCEP and the TPP be path ways to FTAAP?*

* Contributed by Peter A. Petri and Ali Abdul- Raheem. The authors are grateful to Wendy Dobson, Charles Morrison, Eduardo Pedrosa and Jeffrey Schott for comments on an earlier draft.

The vision of free trade in the Asia Pacific has remarkable staying power. Nearly fifty years after it was first proposed (Regional free trade was formally proposed at a 1967 conference organized by Professor Kiyoshi Kojima of Hitotsubashi University. The conference led to the creation of the Pacific Trade and Development Forum (PAFTAD) in 1968 and, indirectly, the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC) in 1980. These set the stage for the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) initiative in 1989 (Patrick, 1996)), it is gaining traction due to the emergence of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) initiatives and the continuing stalemate in global trade negotiations.

As host of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in 2014, China has made the Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP) a priority. A wide regional agreement could generate large benefits and help to overcome stubborn challenges to economic integration in the region and the world.

RCEP and the TPP are critical—and arguably indispensable—steps toward FTAAP, but will not guarantee its realization. They will promote economic integration among members, but will not offer comprehensive regional coverage or, at first, broadly acceptable rules. Since neither negotiation includes both China and the United States, much of the economic and political benefits of regional economic integration would be still unrealized. At worst, the two agreements could establish conflicting standards that are difficult to reconcile and would make the “noodle bowl” of overlapping trade agreements more intractable. Intensified discussions of FTAAP could help to turn the current negotiations, into stepping stones rather than stumbling blocks on the path toward it.

Some paths to FTAAP—indeed the simplest paths —would involve the conclusion of RCEP and TPP and the enlargement of one or the other to cover the region. But another would be to create a new “umbrella agreement” to complement RCEP and the TPP. We examine these pathways, estimate benefits on them, and show that the largest gains would result from those that consolidate RCEP and TPP under high standards. We consider one pathway in depth—an FTAAP umbrella agreement that would set relatively high standards, encourage liberalization across the Asia-Pacific, and offer alternative levels of rules to diverse economies. The obstacles to such positive outcomes and the time required to achieve them cannot be underestimated. The building blocks of the regional system, RCEP and the TPP, face strong political opposition (A recent global survey shows wide skepticism about the employment effects of trade agreements in the United States and many other advanced economies (Pew Research Center, 2014). These views may change once governments enter the debate; lacking concrete results so far, most have not yet launched a vigorous case for new trade agreements) in many economies despite their overall benefits. Efforts to integrate these agreements will be still more difficult and will require a favorable geopolitical environment. Yet the opportunities are also great.

APEC and FTAAP

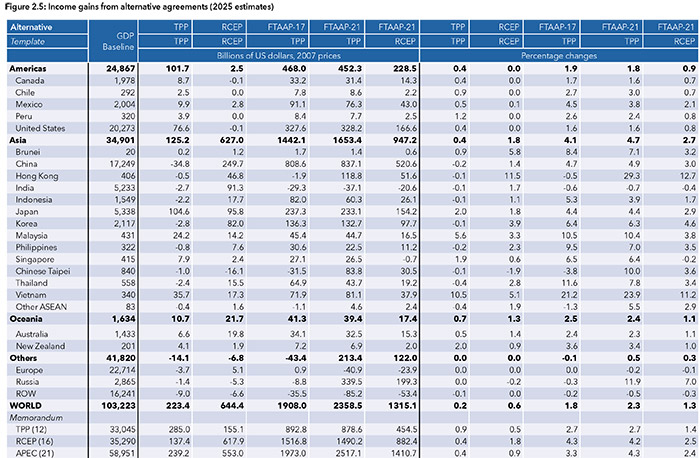

APEC’s historic goal is region-wide economic integration. As one of its principal architects, Prime Minister Bob Hawke of Australia, put it, APEC’s job is to “investigate the scope for further dismantling of barriers to trade within the region” (Hawke, 1989). The Bogor Declaration of 1994 made this vision concrete by committing to “free and open trade and investment in the Asia-Pacific no later than the year 2020” (APEC, 1994). Related initiatives by APEC and its member economies are summarized in Figure 2.1. APEC members have made significant progress toward the Bogor Goals, reducing average applied tariffs from 16.9 percent in 1989 to 5.8 percent in 2010 (APEC Policy Support Unit, 2012), but the 2010 target of full liberalization by developed members was not met, and it is widely expected that the 2020 target for developing members will be also missed.

The high bar of the Bogor Declaration nevertheless continues to attract region-wide support. What would be the best way to make progress toward it—global, regional, or unilateral liberalization? The global route seems blocked, and unilateral policies are sometimes moving in a reverse direction. In 2004, the APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC) proposed a “Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP) to consolidate and accelerate progress toward achievement of APEC’s Bogor goals” (Scollay, 2004). In 2006, US President George W. Bush noted that the idea “deserves serious consideration” (Bush, 2006) and the Leaders’ Summit of 2006 “instructed Officials to undertake further studies on ways and means to promote regional economic integration, including a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific” (APEC, 2006). The resulting study concluded that “APEC should target a high quality and comprehensive FTAAP agreement” (APEC, 2009).

The Leaders’ Summit in Yokohama in 2010 provided further detail, noting that FTAAP “should be comprehensive, high quality and incorporate and address ‘next generation’ trade and investment issues” (APEC, 2010). The Leaders also identified regional and trans-regional liberalization initiatives—including the TPP, the ASEAN+3 and the ASEAN+6 processes—as potential pathways to FTAAP. ABAC recently suggested adding the new Pacific Alliance, comprising four Latin American economies, as a further pathway (ABAC, 2014).

APEC support is essential for FTAAP, but the forum will not be the venue for hammering out an agreement. Since 1998, when the “Early Voluntary Sectoral Liberalization” initiative failed, APEC has focused on non-binding, voluntary projects, including reducing trade costs and acting as an incubator for initiatives by subgroups of members. APEC discussions helped to clarify the details of the Information Technology Agreement (ITA) in 1996 and the proposed Environmental Goods Agreement, and APEC served as a “midwife” to the four-country TPSEP trade agreement. Through its network and analytical initiatives, APEC can also promote region-wide agreements. It has already produced model templates for FTAs (under the 2005 Busan Roadmap) and reviewed the convergences and divergences of regional trade agreements in 2008 (APEC, 2008).

China is showing interest in the FTAAP in the run-up to the Leaders’ Meeting in Beijing in 2014 (Bergsten (2007) argued that China’s “support, on top of that of the United States, Japan, and the other APEC members … would clinch the launch of serious negotiations” on FTAAP. Morrison and Pedrosa (2007) noted that China, Japan or the United States (or perhaps all three) would have to be champions of FTAAP to make it viable. The three economies are still not jointly committed to FTAAP in 2014, perhaps because of geopolitical strains, or because the United States and Japan see the TPP as a difficult enough priority). In April 2014, Premier Li Keqiang called for a feasibility study (Li, 2014) In Qingdao, APEC Ministers Responsible for Trade (2014) endorsed drafting a “roadmap for APEC’s Contribution to the Realization of an FTAAP” and other measures. A prominent Chinese expert has suggested conducting the feasibility study over 2015-16, beginning negotiations in 2017 and concluding them by 2020, the target year of the Bogor Declaration (Y. Zhang, 2014a). The concreteness of these proposals is noteworthy, although the timeline itself is probably too optimistic. As Tang & Wang (2014) note, discussions about the future of FTAAP still need to resolve fundamental questions about “scope, standards, leadership and membership.”

The successful conclusion of the RCEP and TPP negotiations would help to advance FTAAP in the longer run. These agreements would develop FTA templates acceptable to key subsets of APEC members and serve as test beds for new trade rules and adjustments to them. In some countries, they may help to accelerate urgent domestic reforms that would also make future integration more likely. Regional attention would be focused on the results and interactions of the new FTAs, ideally promoting consolidation. For economies that are not members of both tracks, like China, “there might be practical ways … to integrate the TPP pathway with the RCEP pathway in the future” (J. Zhang, 2014). None of this can be expected to happen quickly or smoothly, but launching an FTAAP study in 2014, as China proposed, would be a timely starting point for related work.

The Pathway Strategy

As APEC Leaders noted in 2010, FTAAP is likely to require a pathway—that is, initiatives that prepare the ground for regional agreements by connecting groups of members. Both Asian and Trans-Pacific negotiations aspire to become such pathways by developing 21st century trade rules, albeit their approaches differ. Before examining this progress, we briefly review economic theories of pathways—that is, the dynamics of regional integration. These theories offer insights and benchmarks for evaluating the processes underway.

What are pathways?

Much work on trade liberalization focuses on single outcomes, such as the effects of specific free trade areas. The benchmark for such analysis is free trade and much early work—including the classic study by Viner (1950)—examines how closely an agreement approximates that standard. Recent work (This literature is summarized in the survey by Baldwin & Freund (2011)), however, recognizes that economies seldom establish a free trade regime at once but rather negotiate a series of agreements toward it. Europe’s path to a customs union started with six members in the Treaty of Paris in 1951 but now includes 28 countries. Dynamic effects are important. Economic integration combines a series of unilateral actions, bilateral and regional liberalization, the enlargement of existing free trade areas, as well as global negotiations. In the post-World War II period these strategies resulted in extensive, world-wide reductions in trade and investment barriers.

In an influential paper, Krugman (1991a) showed that the enlargement of trade blocs could lead to very poor outcomes—a world with three giant blocs that erect high barriers against each other. In his model, economies formed blocs in order to increase their market power and improve their terms of trade against other blocs. The end result was an equilibrium with three giant blocs that imposed high barriers and, among alternative configurations of blocs, minimized world welfare. However, another paper by Krugman (1991b), published almost simultaneously, showed an opposite effect. In that paper, economies that formed blocs already traded extensively with each other. The bloc then created more internal trade, rather than exploiting market power against outsiders. This pathway led to positive global effects. Frankel, Stein, & Wei (1995) later showed that several actual regional groupings tend to be “natural trading blocs.” The Asia-Pacific easily meets the requirements of such a bloc.

Studies that focus on the political economy of trading blocs generally produce more positive results. These emphasize not total gains, but benefits to political actors within economies. Baldwin’s (1993) domino theory of regionalism argues that as a bloc grows, potential partner economies benefit more from joining and offer deals good enough to tilt the political calculus within blocs toward enlargement. Blocs that gain critical mass—for example, the European free trade area—thus attract steadily growing membership. Another mechanism presented in McCulloch & Petri (1997) argue that the political constituencies within blocs change as they grow. As a result of a free trade area, efficient firms become more plentiful and inefficient firms disappear. Thus, blocs can become increasingly open to new members. Petri (2008) shows that once a region is saturated by bilateral and plurilateral agreements, the calculus of liberalization favors their consolidation. With many agreements in place, preference erosion reduces the value of each bilateral agreement, while rising administrative costs argue for merging them.

The TPP pathway

Since 1998, APEC has encouraged groups of economies to experiment with “pathfinder” initiatives that may include binding commitments. One such initiative (though officially not labeled a pathfinder) was the high quality Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership (TPSEP, now called P-4) agreement among Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore, launched on the sidelines of the 2002 APEC Leaders’ Summit and concluded in 2005. The United States announced its intention to enter negotiations with the group in 2008, and Australia, Peru and Vietnam also joined in that year. Negotiations began in March 2010 and four economies have been added since: Malaysia in 2010, Canada and Mexico in 2012, and Japan in 2013. Korea, the Philippines, Chinese Taipei and Thailand have also expressed interest, and China and Indonesia have indicated that they are following the negotiations closely.

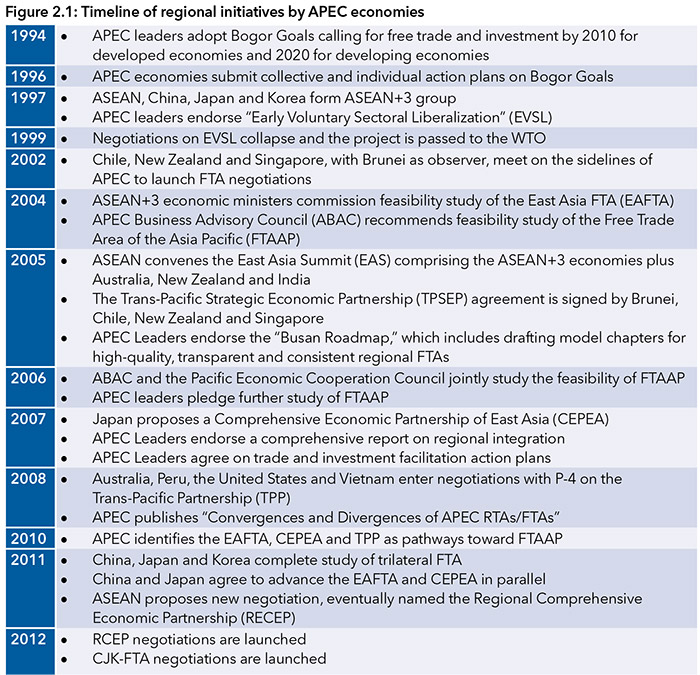

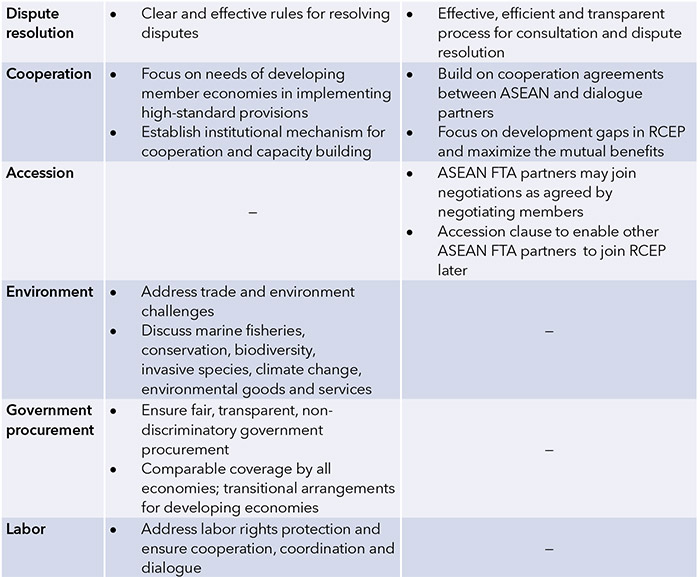

The emerging content of the TPP reflects the diverse economic structures and governance of its members, and their high level of interdependence. Major trade agreements already exist among many of them. Negotiators are thus seeking a “21st century agreement” that will be comprehensive, high quality, and beneficial to both developing and industrialized members. The official objectives of the TPP are summarized in Figure 2.2 and compared with those of RCEP.

As the table suggests, TPP participants are grappling with highly controversial issues such as intellectual property, services, investment, government procurement, labor and environmental standards. The negotiations have not yet resolved disagreements on some of these.

In the fall of 2014, with 19 rounds of negotiations completed, TPP negotiators have arrived at possible solutions to many problems—which they call “landing zones”—even as conclusions await decisions from high levels of government. An important source of uncertainty is US politics; the Congress has not granted trade promotion authority (TPA) to the President, and “fast track” procedures (Fast-track procedures such as TPA commit Congress to a yesor- no vote on a trade agreement, eliminating decisions on individual provisions that could unravel compromises. Of course, TPA would be useful throughout a negotiation. However, some political observers argue that, when Congress is sharply divided, a fast-track bill cannot be expected until an FTA is nearly complete and its advantages can be more persuasively argued (Cooper 2014)) may be necessary to conclude the negotiations. Nevertheless, some believe that an agreement in principle can be reached either before or not long after the US congressional elections in November 2014.

If concluded on this schedule, the TPP will have first-mover advantage among the pathways toward FTAAP (Schott, 2014). Supporters believe that a successful agreement will then lead to the inexorable enlargement of TPP membership until essentially all FTAAP economies are admitted. Building on an existing, complete agreement would be the fastest way to move forward, and some exceptions could be still granted to accommodate the sensitivities of new entrants. But this scenario could prove too optimistic: some TPP provisions may not be acceptable to key potential entrants like China because they represent standards that are either too high or too closely tied to the preferences of the original TPP members. Negotiations between potential new members and incumbent TPP members, which include economies whose preferences may be eroded by the admission of new members, will also present hurdles. Connecting the TPP with other FTAAP economies may therefore require substantial additional agreements.

The RCEP pathway

RCEP is partly the result of sustained efforts by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to promote regional economic integration. An ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) was concluded in 1992, followed by a deeper and wider effort, the ASEAN Economic Community, launched in 2007. ASEAN also helped to develop the Chiang Mai Initiative in 1997, a multilateral currency swap agreement among ASEAN, China, Japan and Korea. In 2002, ASEAN and China initiated a framework agreement for an FTA, which was later followed by similar agreements with the other “plus six” partners, Australia, India, Japan, Korea and New Zealand.

Due to political tensions in Northeast Asia, wider regional cooperation emerged slowly. In 2005 a feasibility study was undertaken on an East Asia FTA (EAFTA) consisting of ASEAN plus China, Japan and Korea. Also in 2005, ASEAN convened the first East Asia Summit (EAS), consisting of the ASEAN+6. In 2007, Japan proposed a new FTA project based on the EAS, to be called the Comprehensive Economic Partnership of East Asia (CEPEA). For several years, EAFTA and CEPEA represented competing visions of regional integration, backed by China and Japan, respectively. At the 2011 ASEAN Summit in Bali, China and Japan finally agreed to allow both tracks to proceed, and in 2012 ASEAN developed an approach that came to be formalized as RCEP.

RCEP is based on the ASEAN+6 economies and its “Guiding Principles and Objectives” call for “a modern, comprehensive, high-quality and mutually beneficial economic partnership agreement… [to] cover trade in goods, trade in services, investment, economic and technical cooperation, intellectual property, competition, dispute settlement” (ASEAN 2012). The Principles stress flexibility and the agreement is expected to include “special and differential treatment” for developing members (Urata, 2014). As Figure 2.2 suggests, the agreement will be confined mainly to market access and connectivity issues (reflecting the region’s focus on production chains) rather than “behind-the-border” rules targeted by the TPP.

Negotiations were launched in late 2012 with 2015 as the target date for agreement. Little is known about details. Observers expect RCEP to emerge in phases and a 2015 outcome may include only market access issues (Urata, 2014). As Figure 2.2 suggests, RCEP does not intend to negotiate provisions on labor, environment and government procurement, and its provisions in other areas may adopt intermediate standards. It is not known whether members will apply common market access schedules to all partners, as some economists hope. Some question to what extent RCEP will be able to improve existing ASEAN FTAs (which have been concluded with all RCEP members) or whether it can result in a meaningful agreement among China, India, Japan and Korea. Observers expect RCEP to be “guided by the ‘ASEAN way’ where objectives and commitments are driven by a consensus process,” to be accommodative (Das, 2013), and to produce only modest reductions in tariff barriers (Urata, 2014).

While RCEP’s directions remain uncertain, the negotiations may not reach the level of ambition that liberal supporters hope and advanced economies expect in a regional agreement. Also, some observers see RCEP not so much as a step toward common rules, but as a “counterbalance to the new rule-making process championed by the developed economies” (Yi, 2014; Y. Zhang, 2014b). If so, it would become still harder to gain support from developed economies. On this pathway too, new agreements will need to be developed to achieve region-wide integration.

How the Pathways Might Work

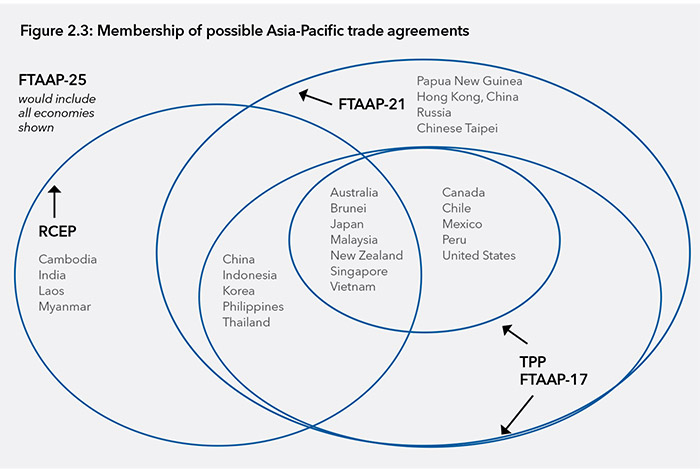

The simplest path to FTAAP, as already noted, would be to approach region-wide coverage by expanding, say, the TPP to 17 economies, including China (Petri, Plummer, & Zhai, 2014b; See Figure 2.3). Such enlargement could yield positive benefits for incumbent TPP members as well as new entrants, and some high-level attention is already directed toward it6. But it may turn out that neither RCEP nor TPP provisions are acceptable, at least at first, to all economies outside their negotiating groups. In that case FTAAP would require building a new, umbrella agreement around RCEP and the TPP. A “hybrid” approach proposed by Schott (2014) has some similar features. This section examines the logic of the umbrella path, ranging from membership to the harmonization of specific provisions.

Membership

The economic structure of the Asia-Pacific has changed dramatically since APEC was launched in 1989. APEC membership, which has been updated modestly, no longer coincides with the region’s major trading relationships. An early, difficult choice therefore concerns the definition of an FTAAP negotiating group. RCEP membership is based on ASEAN’s FTA partners, while the TPP represents self-selected APEC economies. If FTAAP were to be based only on participants of RCEP and the TPP, it would have to go beyond APEC membership and also include Cambodia, India, Laos and Myanmar, while excluding Hong Kong (China), Chinese Taipei, Russia, and Papua New Guinea. Further, as Scollay (2014) notes, additional non-APEC members may eventually join RCEP and the TPP.

Since an FTAAP negotiation would be independent from APEC, there is no strict requirement to link the memberships of the two groups. Three possibilities for defining FTAAP membership are illustrated in Figure 2.3. Decisions on the membership of FTAAP will have to strike a balance between inclusiveness and limiting the negotiations to the economies most committed to reaching an agreement. First, since the FTAAP concept arose in APEC, an obvious possibility is to define membership in terms of APEC’s 21 members. A second, a more inclusive option is to expand the group to 25 members, by including economies in RCEP and TPP that are not members of APEC (perhaps by admitting them into APEC). A third intriguing option is to limit the initial negotiations to the 17 economies that (a) are APEC members, and (b) are participating in the RCEP and/or TPP agreements. This group has demonstrated the greatest commitment to regional trade and has accumulated the most experience with regional and sub-regional institutions.

Decisions on the eight economies that fall outside the 17-member configuration but within the 25-member group will be especially difficult. To be sure, political circumstances are likely to change by the time an FTAAP negotiation begins. If political trends favor regional integration, they will also make the resolution of membership issues less contentious than it would be today. Moreover, additional members—from within or outside APEC, including additional economies from the Pacific Alliance—could be added after an agreement is completed. Intermediate solutions would involve forming a relatively small negotiating group, along with a commitment to timely, favorable accession procedures for other Asia-Pacific economies.

The logic of an umbrella agreement

An umbrella agreement would be separate from RCEP and the TPP, although it should be shaped by their provisions. Since the two smaller agreements will differ, FTAAP will have to take positions on some issues that are absent from at least one of the agreements as well as harmonize provisions that are included in both.

Economies that have negotiated less ambitious rules previously (say in RCEP) will need to adopt more demanding ones in FTAAP. And others that have accepted more ambitious rules (say, in the TPP) may have to dial back those ambitions. The benefits of FTAAP—including its provisions for broader market access—will have to be large enough to satisfy both of these groups. Of course, members may continue to observe higher standards with partners in existing agreements such as the TPP, and in turn offer larger concessions to them. And some economies may not be ready to move beyond agreements that require more limited commitments, such as RCEP. The result would be a multi-tiered system, with RCEP, FTAAP or TPP representing successively higher standards—much as economies today build on their WTO commitments in FTAs with “WTO-plus” obligations.

Under the FTAAP umbrella, members might be expected to converge to higher standards. This could happen as economies join the TPP (so more and more trade under the umbrella agreement would be governed also by TPP standards) or by upgrading FTAAP, construed as a living agreement. Precedents for an evolutionary approach to standards are offered by ASEAN’s upgrading of the ASEAN Free Trade Area and some ASEAN-plus-one partnerships. NAFTA is itself an umbrella agreement built around the Canada-US free trade agreement and has been upgraded over time, for example, in its rules of origin. The TPP is also envisioned to be a “living agreement” to be adjusted in the future. That said, the political process in the United States makes such adjustments in trade agreements difficult.

Bilateral provisions

A large subset of issues within FTAAP could be resolved in bilateral negotiations among members not already connected by an FTA. To make such a strategy possible, the FTAAP would absorb existing market access commitments among economies that already have agreements. New bilateral negotiations would be limited to economies that do not already have an agreement (either directly or through RCEP or TPP). This is how the TPP avoided multilateral negotiations on market access and the renegotiation of existing agreements. The remaining bilateral deals will be still difficult—as demonstrated by the Japan-US negotiation in the TPP—and China-US negotiations are likely to be especially challenging. Finding bilateral solutions to important issues is hardly a perfect solution—it leads to discrimination even within an FTA—but it can make negotiations more manageable.

Cooperation between China and the United States will be critical on bilateral as well as plurilateral provisions, so prior China-US agreements on relevant issues would greatly improve prospects for a region-wide agreement (An analysis of steps toward China-US free trade is provided by Bergsten, Hufbauer, & Miner (2014) and, in that volume, by Petri, Plummer, & Zhai (2014a)). Some trends are encouraging. Direct discussions between the two economies are already underway on investment issues, and on services, government procurement and other issues in the WTO context. Also, FTAs concluded by the two economies with third partners can promote common approaches to international rules. China either has or is negotiating FTAs with 9 of the 12 TPP members. Only Canada, Mexico and the United States are not on this list at this time. Significantly, a China- Korea FTA is said to be near completion, and this agreement will presumably mirror some features of the high quality agreement that Korea recently concluded with the United States.

Harmonized provisions

Issues not negotiated bilaterally will require text that spans the difference between RCEP and the TPP. One would expect that most differences may be resolved with intermediate positions. The minimum years of protection for an intellectual property asset, for example, could be set higher than in RCEP (which may just stick with TRIPS standards) and lower than in the TPP. The “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the RCEP” have so far only identified the WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) and the ASEAN FTAs as guidelines for service sector liberalization. As Anuradha (2013) explains, these are modest benchmarks: many economies in fact are already pursuing a more ambitious agenda in various forums, such as the “ASEAN Framework Agreement for Services” (AFAS) adopted by the ASEAN Economic Community.

Fukunaga & Isono (2013) calculate a “Hoekman Index” to measure the extent to which ASEAN’s new agreements exceed GATS standards. They generally find ASEAN’s FTAs to have made substantial progress beyond GATS, and further note that service liberalization under AFAS (package 7) surpassed commitments in all FTAs, in part because the latter included opt-out clauses.

Still, intermediate positions will be hard to agree in the service sectors. The TPP approaches services on a negative-list basis, opening all sectors except those explicitly excluded, while RCEP is likely to adopt a positive list. Intermediate text will thus have to determine the negotiating modality as well as the level of sectoral commitments.

Conflicting provisions

Two other kinds of compromises will be also complicated to negotiate. First, RCEP and TPP may have conflicting provisions—for example, different dispute settlement rules. A common position would then require some members to abandon some prior commitments. Such direct conflicts, however, are unlikely. The WTO rules serve as the basis of both RCEP and the TPP, and 7 economies are members of both agreements. They will likely avoid contradictory provisions in the two agreements. Second, some issues may be missing in the RCEP agreement, while being considered critical in the TPP. As Figure 2.2 shows, these include government procurement, state-owned enterprises, labor, environment and others. These provisions are often based on international conventions and standards which member economies are asked to accept. Thus reasonable, WTO-plus intermediate positions will usually exist. Still, some economies often oppose entering certain areas of negotiations altogether. Defining the scope of the agenda broadly while treating issues flexibly will be important in getting the negotiations launched.

Rules of origin (ROO)

Rules of origin are designed to control “trade deflection.” They require goods exported under regional preferences to originate within an FTA zone, rather than merely pass into it through the borders of the member economy with low external barriers. Strict ROO minimize deflection but also make it harder for firms to utilize the benefits of FTAs. ROO are especially important in the Asia-Pacific because they affect the operation of manufacturing supply chains.

Economics strongly favors ROO that are simple, common to all members, and permit cumulation— that is, the practice of counting intermediate inputs produced anywhere in the FTA zone as “originating” and thus eligible for FTA preferences (Plummer, 2007). However, reconciling ROO across the region’s agreements will be difficult (ROO could theoretically differ among RCEP, TPP and FTAAP, separately activating the market-access concessions in each agreement. However, such differences would have complicated consequences. For example, if the FTAAP ROO are less restrictive than the TPP ROO, then the effect of market access commitments made by economies in the TPP would change. In that case, TPP market access provisions might also have to). An APEC (2012) study of existing regional FTAs demonstrated a preference for product-specific ROO over general rules, with details varying widely. A major obstacle to harmonization, for example, is the “yarn forward” rule in textiles and garments that the United States typically includes in trade agreements and is likely to require in the TPP (Schott, Kotschwar, & Muir, 2013).

Still, the ROO negotiations may be surprisingly manageable in FTAAP. The threat of trade deflection is modest in large agreements, since in this case most production will rely on regional intermediate inputs. Even industry-specific rules, such as yarn-forward, would exert minimal constraints in a setting that includes entire production chains. Moreover, Estevadeordal, Blyde, Harris, & Volpe (2013) show that complex ROO tend to be streamlined over time in a large zone. NAFTA initially applied product-specific rules that were highly restrictive of third-party content, but over the last 20 years progressively eased them in four rounds of amendments. Similarly, FTAAP could lead to improvements in the region’s ROO regime.

In sum, RCEP and the TPP represent foundations for an FTAAP. They provide way-stations for experimenting with and adjusting to deeper integration. This is important for the large trade flows that connect the United States, China and Japan with each other and other partners. To be an effective way-station, FTAAP needs to be ambitious enough to move beyond RCEP toward the TPP. Yet it also has to provide flexibility to attract broad membership. Much effort and ingenuity will be needed to achieve this balance.

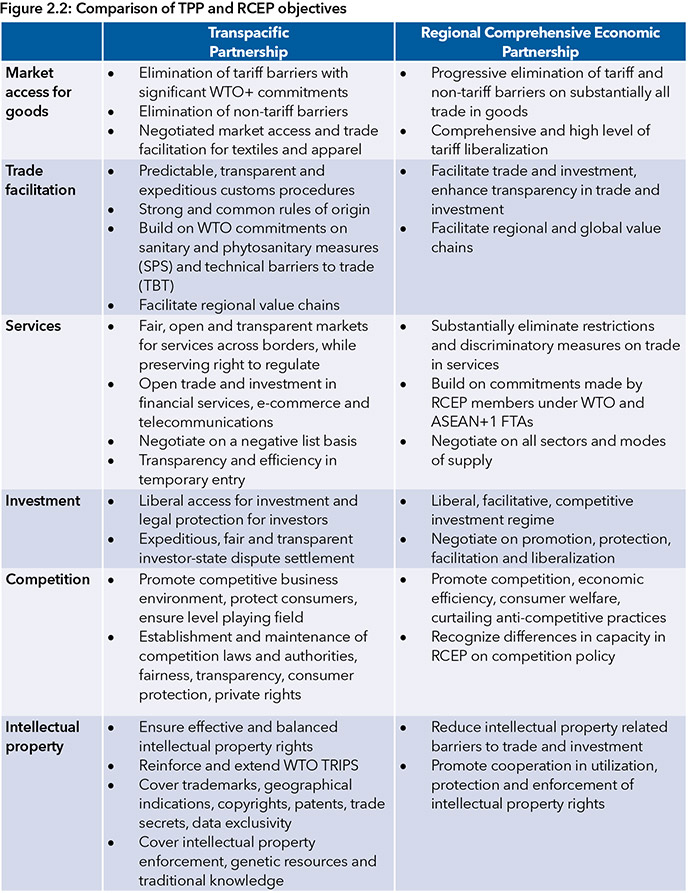

The Benefits

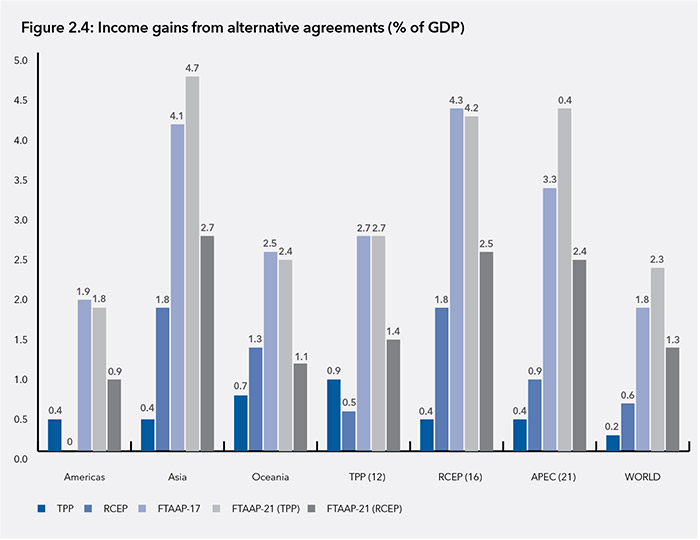

We conclude with estimates—inevitably uncertain— of gains from FTAAP pathways. These are based on an advanced, computable general equilibrium (CGE) model (The details of the model cannot be included here, but they are fully described in Petri, Plummer, & Zhai (2012) and on the website asiapacifictrade.org) to simulate the 12-member TPP, the 16-member RCEP, and two variants of FTAAP, one with 17 economies (FTAAP-17, based on APEC members that also participate in RCEP or TPP) and another with all 21 APEC economies (FTAAP-21). The benefits of FTAAP are assessed for two levels of standards, those expected to be included in the TPP, and those expected in RCEP. The estimates rely on new data on the provisions of trade agreements in order to make the trade policy simulations realistic. Detailed information on issues covered in nearly 50 regional trade agreements has been used to assign ”scores” to the quality of these agreements in 24 dimensions. Future agreements are assumed to use templates comparable to those used in the past by similar economies. For example, the TPP’s template is based on that of the Korea-US free trade agreement, and RCEP’s template on those included in recent agreements by ASEAN. The templates differ significantly on issues such as government procurement, intellectual property rights, investment, and competition, as well as the depth of liberalization of tariff and non-tariff barriers.

The results summarized in Figure 2.4 (based on the detailed results reported in Figure 2.5) suggest several key conclusions. Most importantly, the benefits of Asia-Pacific integration are estimated to be large; for strong, comprehensive agreements income gains could reach 2.3 percent of world GDP in 2025 or US$2.4 trillion. But even the current negotiations on the TPP and RCEP would generate substantial gains. RCEP shows the larger benefits of the two (0.6 percent compared to 0.2 percent of GDP), due largely to the effects of trade liberalization among China, India, Japan, and Korea.

There are, to be sure, significant differences in how the agreements would affect Asia-Pacific economies. The TPP favors economies that do not yet have an FTA with the United States, such as Japan and Vietnam. At the same time, the TPP generates trade diversion losses for China, Europe and Asian economies not included in the agreement. RCEP favors China, India, Japan and Korea because it assumes—perhaps too optimistically—major trade liberalization among these economies as part of RCEP. ASEAN economies would gain only modestly in RCEP, since FTAs already cover ASEAN’s relations with all RCEP partners. The significant contribution of an FTAAP would be an agreement between China and the United States, which would sharply increase overall gains.

Significantly, as the theoretical analysis of modern trade agreements suggests, much of the benefits of integration accrue to economies with the highest initial barriers—this is why the gains of Asian economies are generally higher than those of other groups. In addition, a vast majority of benefits in all of the agreements would reflect trade-creation and productivity increases within them, rather than trade diversion from outsiders. Even for the TPP, the smallest group among those examined, total trade diversion losses affecting China and some other economies would represent only 22 percent of the benefits of gainers, with the remaining 78 percent reflecting trade creation. For the larger FTAAP-21, the ratio of diversion losses to total gains would fall to 6 percent.

Finally, the benefits from alternative agreements confirm well-established expectations given their size and quality. Potential gains increase sharply with the scale of integration—for example, expanding the TPP with 12 members to an FTAAP with 17 members would increase global benefits from $223.4 billion to $1,908.0 billion in 2025. The benefits would grow further to $2,358.5 billion if Hong Kong (China), Chinese Taipei, Papua New Guinea and most importantly Russia were added under the APEC membership-based FTAAP-21. Still larger benefits could be achieved if India, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar were added to form an FTAAP-25 (these results are not shown in Figure 2.4). Similarly, gains increase with the quality of the agreement, or specifically the ambition of its template. The benefits of the 21-member FTAAP, for example, would be $2,358.5 billion with the more rigorous TPP-style template with APEC membership compared to $1,315.1 billion with an RCEP-style template, some 79 percent higher. The benefits would extend to all economies, even to Asian economies which might have been expected to gain more from their “own” template incorporated into RCEP.

Conclusions

Asian and trans-Pacific regional negotiations are moving forward, despite business cycles, elections, geopolitics, and political controversy. Pathways toward the FTAAP are also garnering new interest. Estimates suggest that they could generate large economic benefits. The gains will depend on the size of the ultimate agreement and the quality of the templates used. There is tension between these objectives—a rigorous template, as in the TPP, yields greater gains, but also impedes participation. However, there are ways to balance these extremes, through a multi-tiered process that eventually includes an FTAAP.

While the case for FTAAP is compelling, achieving an agreement on this scale is at best a challenging, long-term prospect. Detailed policy recommendations are premature and would go beyond the scope of this paper in any event. Nevertheless, the following broad issues merit attention:

- APEC has long recognized the value of region-wide free trade. Progress on the RCEP and TPP negotiations would make FTAAP more likely and the analysis of pathways to achieve it more timely.

- RCEP and the TPP would provide essential way-stations for economies on the path to region-wide integration. These agreements are likely to differ on many difficult issues. Still, they are unlikely to include contradictory provisions, and region-wide membership would make it easier to address ROO, an unusually contentious issue in trade negotiations.

- FTAAP promises huge benefits, on the order of $2 trillion annually. The benefits would be widely shared in the region. Their scale would depend on the breadth of the membership and the quality of the agreement negotiated.

- The prospects for integration depend most importantly on cooperation between the region’s two largest economies, China and the United States. This could involve early milestones such as a bilateral investment treaty and joint support for plurilateral initiatives in the WTO. China-US agreements— like Japan-US agreements in the TPP— would dramatically improve the prospects for FTAAP.

Deeper economic integration in the Asia-Pacific would produce large economic gains and could help to defuse dangerous geopolitical tensions. To be sure, agreements that foster integration will be very difficult to achieve. Lengthy and complex negotiations may be required and much opposition is bound to emerge from special interests throughout the region. Asia-Pacific integration will depend on farsighted, collaborative leadership, not least from the region’s largest economies.

References

ABAC. (2014). Asia-Pacific business leaders urge APEC to accelerate the process for achieving a Free Trade Area in the Asia- Pacific region. Retrieved September 29, 2014, from http://www.apec.org/Press/News-Releases/2014/0508_fta.aspx

Anuradha, R. V. (2013). Liberalization of Trade in Services Under RCEP: Mapping the Key Issues. Asian Journal of WTO & International Health Law and Policy, 8(2), 401–420. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=2385520

APEC. (1994). 1994 Leaders’ Declaration. Retrieved from http://www.apec.org/Meeting-Papers/Leaders-Declarations/1994/1994_aelm.aspx

APEC. (2006). 2006 Leaders’ Declaration. Retrieved from http://www.apec.org/Meeting-Papers/Leaders-Declarations/2006/2006_aelm.aspx

APEC. (2008). Identifying Convergences and Divergences in APEC RTAs/FTAs (2008/ CSOM/016rev1) (Vol. 2014). Singapore: Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.

APEC. (2009). Further Analytical Study on the Likely Economic Impact of an FTAAP. Singapore. doi:2009/CSOM/R/010

APEC. (2010). 2010 Leader’s Declaration. Retrieved from http://www.apec.org/Meeting-Papers/Leaders-Declarations/2010/2010_aelm.aspx

APEC Ministers Responsible for Trade. (2014). Qingdao Statement. APEC.

APEC Policy Support Unit. (2012). APEC’s Bogor Goals Progress Report (Vol. 2014). Singapore: Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.

ASEAN. (2012). Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. Jakarta: ASEAN.

Baldwin, R. (1993). A Domino Theory of Regionalism (No. 4465). Cambridge, Mass.

Baldwin, R., & Freund, C. (2011). Preferential trade agreements and multilateral liberalization. In World Bank (Ed.), Preferential Trade Agreement Policies for Development--a Handbook (pp. 121–142). Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Bergsten, C. F. (2007). Toward a Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (No. PB07-02). Policy Briefs in International Economics (pp. 1–11). Washington D.C.: Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Bergsten, C. F., Hufbauer, G. C., & Miner, S. (2014). Bridging the Pacific: Toward Free Trade and Investment Between China and the United States. Washington D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Bush, G. W. (2006). Remarks by the President at National Singapore University. Retrieved from http://2001-2009.state.gov/p/eap/rls/rm/76071.htm

Das, S. B. (2013). RCEP and TPP: Comparisons and Concerns. ISEAS Perspective, (2), 1–9.

Estevadeordal, A., Blyde, J., Harris, J., & Volpe, C. (2013). Global Value Chains and Rules of Origin. The E15Initiative: Strengthening the Multilateral Trading System. Geneva: International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development.

Frankel, J., Stein, E., & Wei, S.-J. (1995). Trading blocs and the Americas: The natural, the unnatural, and the super-natural. Journal of Development Economics, 47(1), 61–95.

Fukunaga, Y., & Isono, I. (2013). Taking ASEAN+1 FTAs towards the RCEP: A Mapping Study (No. DP 2013-02). ERIA Discussion Paper Series. Jakarta: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

Krugman, P. (1991a). Is Bilateralism Bad? In E. Helpman & A. Razin (Eds.), International Trade and Trade Policy. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Krugman, P. (1991b). The Move Toward Free Trade Zones. Economic Review (Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City), 76(6), 5–26. Li Keqiang. (2014). Speech at opening ceremony of Boao Forum. Retrieved from http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-04/10/c_133253231.htm

McCulloch, R., & Petri, P. A. (1997). Alternative Paths toward open global markets. In K. E. Maskus & J. D. Richardson (Eds.), Quiet Pioneering: Robert M. Stern and His International Economic Legacy (pp. 149–169). Ann Abor: University of Michigan Press.

Morrison, Charles E. and Eduardo Pedrosa. (2007). An APEC Trade Agenda? The Political Economy of a Free Trade Agenda in the Asia Pacific. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Patrick, H. T. (1996). From PAFTAD to APEC: Homage to Professor Kiyoshi Kojima. Surugadai Keizaironshu, 5(2), 183–216. Petri, P. A. (2008). Multitrack integration in East Asian Trade: Noodle bowl or matrix? Asia Pacific Issues, 86, 2–12.

Petri, P. A., Plummer, M. G., & Zhai, F. (2012). The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific integration : a quantitative assessment. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Petri, P. A., Plummer, M. G., & Zhai, F. (2014a). The Effects of a China-US Free Trade and Investment Agreement. In C. F. Bergsten, G. C. Hufbauer, & S. Miner (Eds.), Bridging the Pacific: Toward Free Trade and Investment Between China and the United States. Washington D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Petri, P. A., Plummer, M. G., & Zhai, F. (2014b). The TPP, China and the FTAAP: The Case for Convergence. In G. Tang & P. A. Petri (Eds.), New Directions in Asia Pacific Economic Integration (Vol. 2014). Honolulu: East-West Center.

Pew Research Center. (2014). Faith and Skepticism about Trade, Foreign Investment. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Plummer, M. G. (2007). “Best Practices” in Regional Trading Agreements: An Application to Asia. The World Economy, 30, 1771–1796.

Schott, J. J. (2014). Asia-Pacific Economic Integration: Projecting the Path Forward. In G. Tang & P. A. Petri (Eds.), New Directions in Asia-Pacific Economic Integration (pp. 246–253). Honolulu: East-West Center.

Schott, J. J., Kotschwar, B., & Muir, J. (2013). Understanding the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Understanding the Trans-Pacific Partnership (pp. 17–40). Washington D.C.: Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Scollay, R. (2004). Preliminary Assessment of the Proposal for a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP). Issues Paper for ABAC. Singapore: The Pacific Economic Cooperation Council.

Scollay, R. (2014). The TPP and RCEP: Prospects for Convergence. In G. Tang & P. A. Petri (Eds.), New Directions in Asia-Pacific Economic Integration (pp. 225–235). Honolulu: East- West Center.

Tang, G., & Wang, Z. (2014). Pathways to Asia Pacific Regional Economic Integration. Retrieved from http://www.chinausfocus.com/finance-economy/pathways-to-asiapacific-regional-economic-integration/

United States Trade Representative. (2011). Outlines of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, 1–5. Retrieved from http://www.ustr.gov/about-us/press-office/factsheets/2011/november/outlines-trans-pacif

Urata, S. (2014). A Stages Approach to Regional Economic Integration in Asia Pacific: The RCEP, TTP and FTAAP. In G. Tang & P. A. Petri (Eds.), New Directions in Asia-Pacific Economic Integration (pp. 119–130). Honolulu: East-West Center.

Viner, J. (1950). The customs union issue. New York, Carnegie. New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Yi, Q. (2014). The RCEP: A Chinese Perspective. In G. Tang & P. A. Petri (Eds.), New Directions in Asia-Pacific Economic Integration (pp. 131–137). Honolulu: East-West Center.

Zhang, J. (2014). How Far Away is China from the TPP? In G. Tang & P. A. Petri (Eds.), New Directions in Asia-Pacific Economic Integration (pp. 66–77). Honolulu: East West Center.

Zhang, Y. (2014a). Pathway to FTAAP: Presentation to the 2014 PECC General Meeting. Zhang, Y. (2014b). The Institutional Split of Regional Framework: China’s FTA Strategies and the Revival of APEC. Asia Economic Review, 2, 10–13.