Chapter 3 - Perceptions of Growth and Integration in the Asia-Pacific*

* Contributed by Eduardo Pedrosa.

When the region’s Leaders meet in Beijing on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, they will be confronting a plethora of issues.

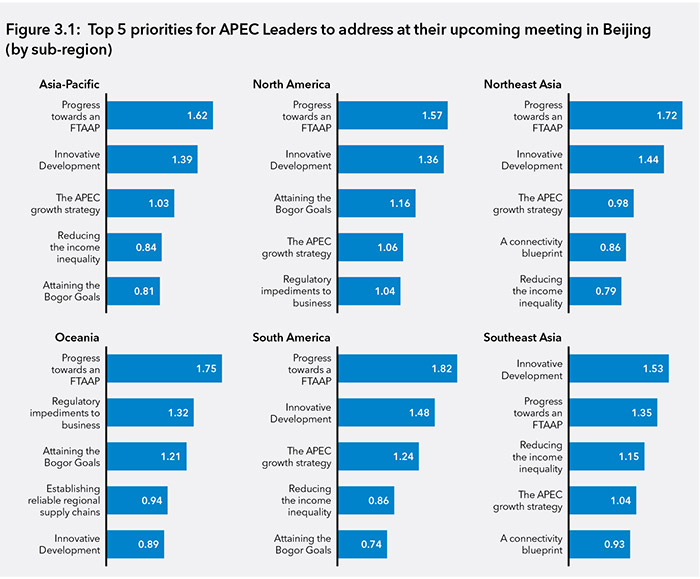

According to a survey of opinion-leaders from the policy community conducted by the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC), the top five issues are:

- Progress towards a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP)

- Innovative development, economic reform and growth

- The APEC Growth Strategy

- Reducing the income inequality in the region

- Attaining the Bogor Goals of free and open trade and investment

The first two correspond to the themes that China has set as priorities for this year as the chair of APEC. While the top five priorities are linked and overlap, they each demonstrate pressing concerns. The FTAAP and the Bogor Goals can be seen as aspirations to address remaining barriers to trade and investment and the future rules of a rapidly integrating region at a time the WTO continues to be mired in controversy over 20th century issues.

Innovative development, economic reform and growth, income inequality and the APEC Growth Strategy all reflect an awareness of the importance of new strategies to respond to the so-called ‘new normal’ of characterized by slower growth, income inequality and slow job creation – especially in major advanced economies.

For a region characterized by great diversity, there was a remarkable degree of convergence on what the top issues should be. Only Southeast Asians did not select progress towards an FTAAP as the top priority which came in second after ‘innovative development’. Respondents from Oceania were the only ones to select ‘establishing reliable supply chains’ as a top 5 priority. Opinionleaders from Oceania and North America thought ‘regulatory impediments to business’ was an important agenda but did not include ‘reducing income inequality’ as a top 5 concern as did the Asians and South Americans.

The Connectivity blueprint, which follows from framework adopted by Leaders last year in Bali, was another issue where there were differences in emphasis: 28 percent of respondents from Southeast Asia selected it as a top 5 priority but only 18 percent of those from Oceania.

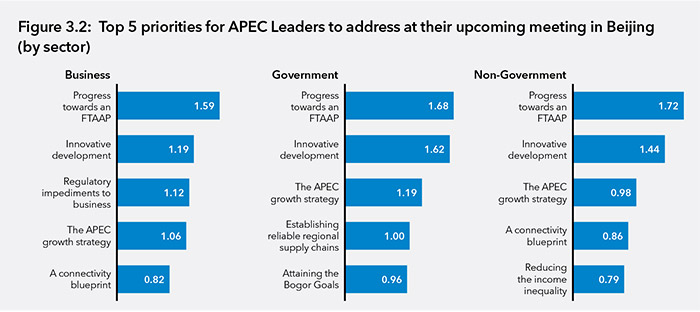

The same level of convergence on priorities is seen among the various stakeholder groups surveyed by PECC, the only differences being higher emphases among business leaders on regulatory impediments, income inequality among the non-government community, and supply chains as well as attaining Bogor Goals from government officials. Interestingly, establishing reliable regional supply chains did not feature as a high priority at all for business leaders with only 15 percent of them selecting it as a top 5 priority compared to 35 percent of government officials who did.

Whither the WTO?

While APEC has been a staunch supporter of the WTO through the years, its stakeholder community is clearly losing patience. It is not just because all sub-regions and stakeholderswhether from government, business or nongovernment - chose what was originally proposed as a Plan B to the Doha Round as the top priority but because a decreasing portion of them think the WTO Doha Round is even worth discussing. Only 13 percent of business respondents thought the WTO Doha Round should be on the APEC Leaders’ agenda. There were also clear differences among sub-regions on this issue with a relatively high 23 percent of respondents from South America selecting it as a priority and only 9 percent of those from North America.

Future of Growth a Key Issue

The list of priorities includes many issues that overlap or are variations on a theme that could easily be subsumed into a broader category. For example, the attainment of the Bogor Goals and progress towards an FTAAP could have been listed as ‘regional economic integration.’ Similarly, innovative development, economic reform and growth could have been subsumed under the APEC Growth Strategy. Were the priorities grouped this way, the Growth Strategy would have topped the list.

As APEC is set to review progress on the Growth Strategy next year, this points to an urgent need for a coherent approach to how regional economies adopt to the new normal. This might provide an opportunity for APEC to consider how it might respond to the G20’s target of increasing baseline economic growth by 2 percentage points by 2018 as part of its commitment to addressing this concern. The approach taken by the G20 has been to set a specific growth target as well as actions that each individual economy will take echoes that of APEC with respect to the Bogor Goals. While the details of the G20 plans are not yet known they will focus on 4 key areas:

- Reducing barriers to trade

- Increasing competition

- Creating more employment opportunities

- Improving infrastructure through increased investment

These are all issues where APEC has set out specific work programs and might be able to widen and deepen commitments to the global agenda.

Economic Outlook

The regional policy community has become increasingly optimistic over the prospects for growth of the world economy over the next 12 months with just under a third of respondents expecting stronger growth and less than a sixth believing there will be slower growth, the lowest percentage in five year.

Respondents were most optimistic about the growth prospects in the United States and Southeast Asia. They were most pessimistic on the prospects of growth for Russia with 67 percent expecting slower growth over the next 12 months, not surprising given the imposition of sanctions. Opinions suggest slower growth for China with 34 percent expecting a slowdown, which compares very favorably against last year’s result when 62 percent correctly expected slower growth for the host of this year’s APEC meetings.

Risks to Growth

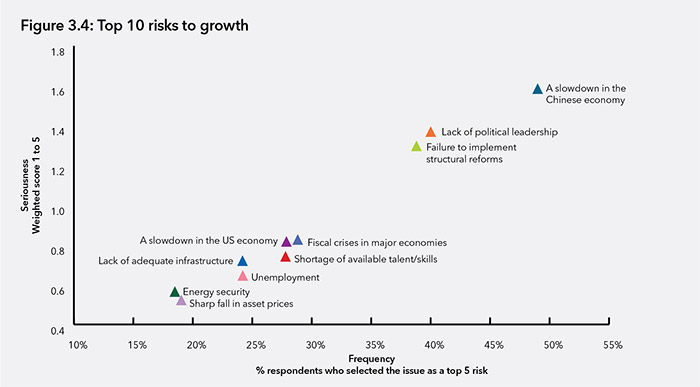

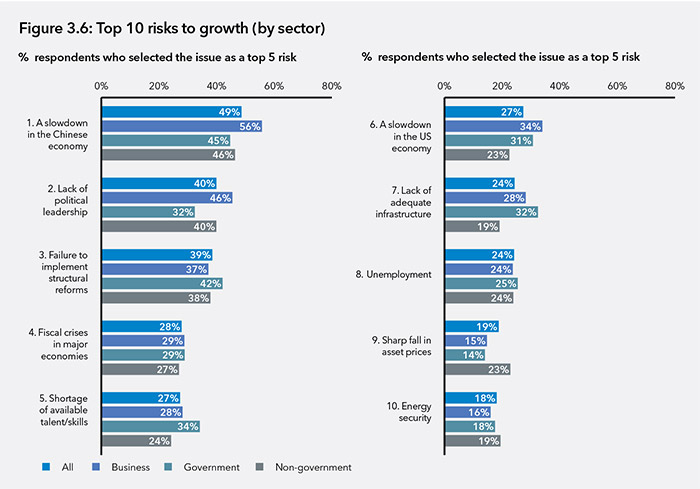

A slowdown in the Chinese economy was once again the top risk to growth amongst regional opinion-leaders – in terms of both the number of respondents who selected it as a top 5 risk as well as its impact.

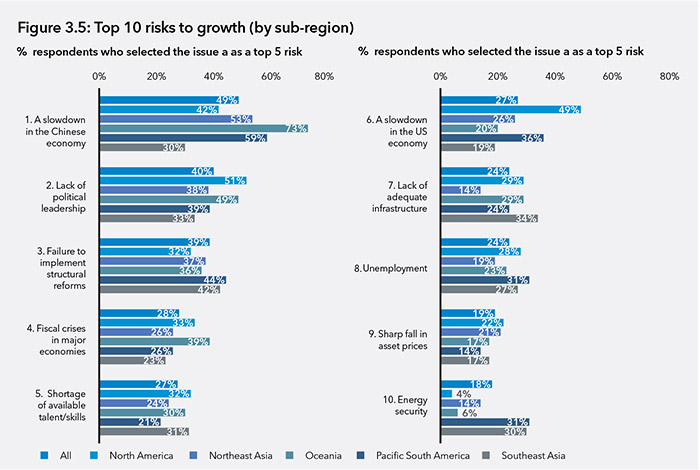

However, the regional breakdown shows some large differences in views. Respondents from resource rich economies in Oceania by far were the most concerned with73 percent of respondents citing a slowdown in China as a top 5 risk to growth for their economy. Respondents from Southeast Asia were considerably less concerned than their counterparts with just 30 percent citing a slowdown in China as a top 5 risk to growth.

Respondents were asked to select the top 5 risks to growth for their economy over the next 2-3 years using a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 showing the least serious risk and 5 the most serious risk. The data gathered by this survey can be shown in a number of different ways. For example, by showing – the risks most frequently selected and the weighted score of each individual risk. For the most part, there is a strong correlation between the two. However, in a number of cases, while a risk might be frequently selected, - suggesting a higher probability of the event happening, the weighted score could be lower if respondents considered its impact to be less serious.

The top 5 risks in terms of the percentage of respondents who selected them were:

- A slowdown in the Chinese economy

- Lack of political leadership

- Failure to implement structural reforms

- Fiscal crises in major economies

- Shortage of available talent/skills

The top 4 in terms of their seriousness were the same, except for shortage of talent. While almost the same number of respondents picked a slowdown in the US economy and a shortage of talent/skills as a top 5 risk to growth (27.4 percent), a slowdown in the US economy was considered more serious scoring 0.85 compared to the shortage of talent which score 0.76.

Figure 3.4 plots the frequency with which respondents selected the risk on the horizontal axis and the severity of the risk on the vertical. Among the top 3 risks there is a strong correlation between the possible severity and the frequency with which opinion-leaders selected the issue. However, while energy security and a sharp fall in asset prices were selected as risks with the same frequency, energy security scored significantly higher in terms of its seriousness. Similarly, the shortage of available talent was cited as frequently as a slowdown in the US economy, but the latter was considered to be a much more serious risk to growth.

While unemployment and the lack of adequate infrastructure were both selected as a top 5 risk by the same proportion of respondents, unemployment was considered to be a slightly less serious.

Lack of Political Leadership – A Shared Concern

Of concern should be the fact that opinion-leaders selected a lack of political leadership as the second highest risk to growth. This was selected a high risk by all sub-regions. It stands as a stark observation if not a rebuke to politicians at a time when leadership is badly needed. Moreover, 46 percent of business respondents selected the lack of political leadership compared to just 30 percent of those from the government. The third highest risk, possible failure to implement structural reforms, also suggests considerable anxiety about the political ability of leaders to address an important regional agenda. As many economies of the region have run out of fiscal space to maneuver and monetary policy is already considered unconventional, getting growth on a higher trajectory will require structural reforms that come with significant adjustment costs in vulnerable sectors.

There were also considerable differences in perceptions of risk among sub-regions. For example, 34 percent of respondents from Southeast Asia selected lack of adequate infrastructure as a top 5 risk to growth compared to just 14 percent of those from Northeast Asia.

For once, the shortage of available talent, which has been rising up the list of risks in recent years, was seen as a higher risk by respondents from government than business which has usually been the case.

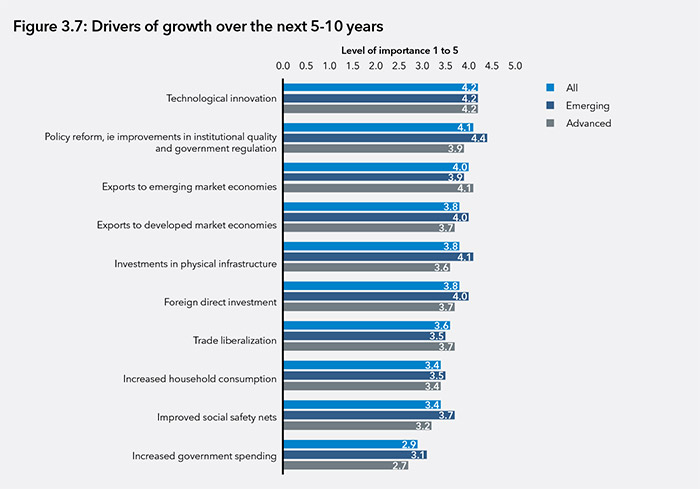

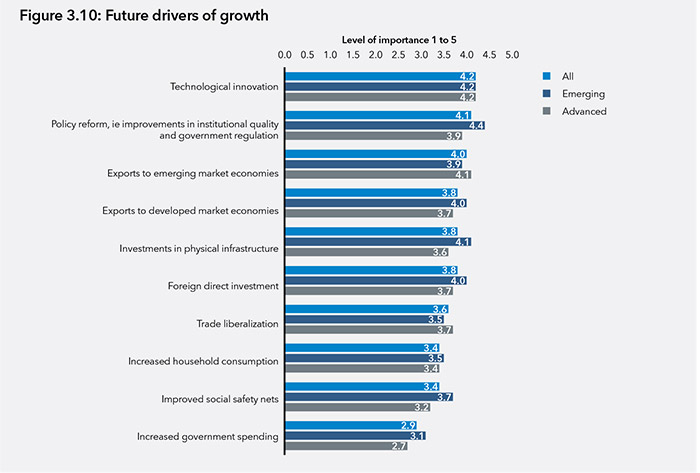

Future Growth and Consumption in the Asia-Pacific

There is a clear need for the region to focus efforts on technological innovation as part of the strategy to overcome the middle income trap. Out of a list of 10 possible drivers of growth, technological innovation was ranked as the most important followed by policy reform and then exports to emerging markets.

As has been widely discussed, the global economy is entering into a ‘new normal’ characterized by slower growth as well as significant changes in the balance of aggregate demand.

The challenge for the policy community is to increase total factor productivity – including innovation as well as institutional quality. Without these improvements, economies of the region risk slower growth. Respondents from middle-income economies placed a much higher emphasis on policy reforms to improve both institutional quality and government regulation than their counterparts from high-income economies.

Interestingly, while respondents from emerging economies tended to see equal importance in exports to other emerging markets as well as developed markets, respondents from developed economies put much more emphasis on emerging market exports than to other developed markets.

Trade liberalization is not regarded as an especially significant growth driver. This may seem at odds with the emphasis placed on the FTAAP as a leaders’ priority, and may reflect the respondents’ belief about what the APEC process can best achieve.

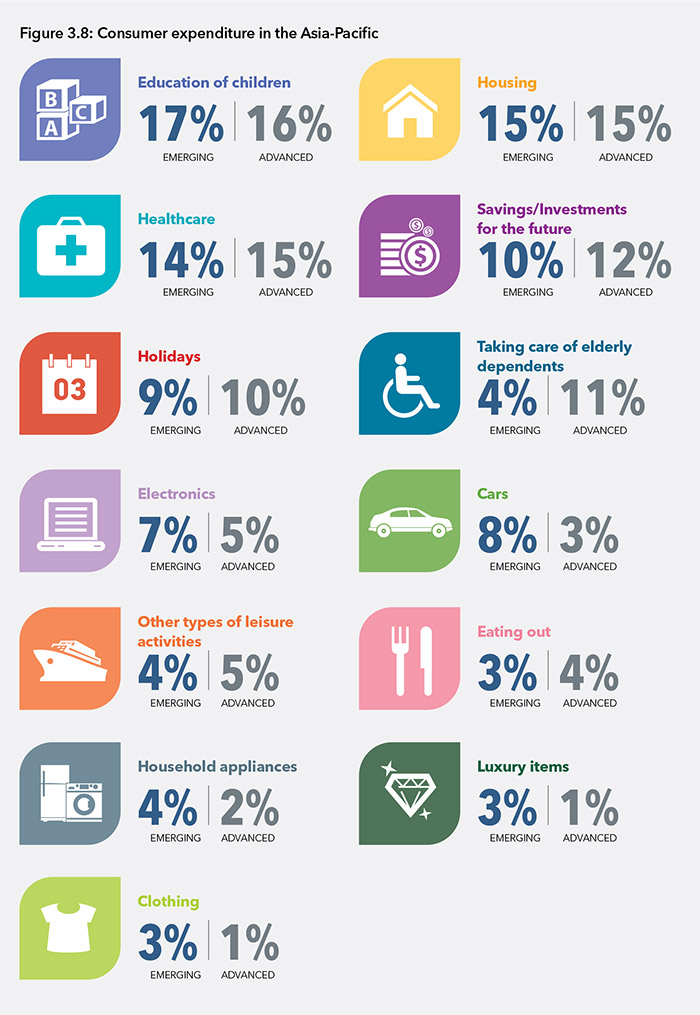

The Future Consumers

There is some speculation that the emerging economies of the region are on the cusp of a consumer boom. The previous decades of growth have brought average incomes in many economies beyond a threshold level – moving from expenditure on day-to-day living to having more discretionary income. Figure 3.8 shows the percentage of respondents who selected each category as an area where they expected consumers in their economy to spend an increasing proportion of their income.

Interestingly there was substantial convergence between respondents from both advanced and emerging economies on the top categories for future expenditure by consumers in their economies – education, housing, and healthcare. Where there were some differences were in categories that might be related to the emergence of new middle class consumers – for example, those from emerging economies were expected to spend more on electronics, cars, luxury items and clothing.

One striking finding is the expectation among opinion-leaders from higher income economies that consumers would be spending more on taking care of elderly dependents. While in general, societies in advanced economies are older and the labor supply for taking care of the elderly more limited, the ageing phenomenon is not limited to high-income economies. This is not an issue of importance only to advanced economies as many emerging economies are yet to put in place the kinds of pension schemes available in high-income economies.

Questions on consumer trends are more typically found in marketing surveys. However, the purpose of including this question in this year’s survey was to relate the changing consumption basket to the broader question of the future of economic growth.

Not surprisingly, big ticket items such as housing, education and healthcare dominated the list.

As discussed in Chapter One, the expectation is that consumption will take up an increasingly high portion of aggregate demand in emerging market economies as incomes pass threshold levels allowing more discretionary expenditure. The survey results show an expectation among the policy community that emerging markets are likely to increasingly be a source of demand for key consumer goods like cars, electronics and household appliances.

Although it is clear that there is a strong expectation that education, healthcare, housing, and savings for retirement are likely to continue to dominate a typical household’s expenditure basket. It also points to a need for more sophisticated financial sector in emerging markets to meet this growing demand.

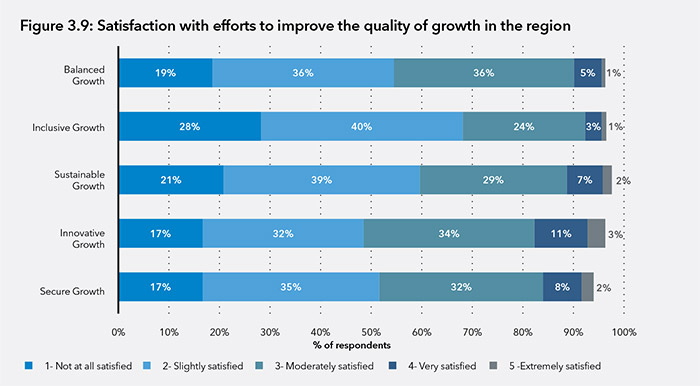

APEC Growth Strategy

In 2010, APEC Leaders agreed that the quality of growth of the region needed to be improved so it will be more balanced, inclusive, sustainable, innovative, and secure. Strikingly, satisfaction with efforts made on each dimension of APEC’s Growth Strategy remains low.

Respondents were asked to rank efforts made under each dimension from a score of 1 to 5 with 1 being not at all satisfied and 5 very satisfied. Across the board grades given were around 2 – equivalent to slightly satisfied. Respondents were most satisfied with actions taken to make growth more innovative with 48 percent expressing extreme to moderate satisfaction. Since the adoption of the growth strategy APEC leaders’ declarations have focused on innovation adopting 2 frameworks for promoting innovation in 2011 and 2012.

Similarly in 2012, APEC economies made a breakthrough promoting sustainable growth by agreeing on a list environmental goods on which tariffs would be reduced to 5 percent or less.

Of concern is that the lowest grades were given to efforts to make growth inclusive. As income inequality is considered a top risk to growth, APEC will need to do more work in this area in the future. Also worth noting that respondents from government tended to give slightly higher marks than counterparts from business and the non-government sectors.

Drivers of Future Growth for Individual Economies

Looking further ahead over the next 5-10 years, respondents were asked to rank how important different factors would be to the future growth of their economies. By far technological innovation was ranked as the most important followed by policy reforms and then exports to emerging markets.

There were significant differences in responses from those from emerging economies and those from advanced economies. Those from emerging economies placed a much higher emphasis on institutional quality and governance – i.e. the types of issues covered by the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Indicators while those from high income economies looked to exports to emerging markets at the second most important driver of future growth.

Increased government spending is not expected to play that significant a role in future growth in either emerging or advanced economies. Respondents in both placed this at the bottom of the list of factors.

The results once again highlight the importance of infrastructure to the future of growth in the region’s emerging markets. Those in emerging markets placed investments in physical infrastructure as the third most important driver of growth for their economies after policy reforms and innovation.

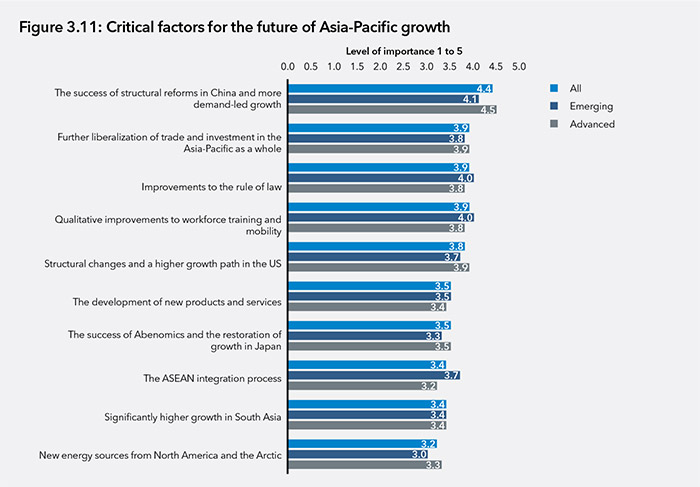

Future Growth in the Asia-Pacific

Figure 3.11 shows the results of the survey for the question on factors affecting growth prospects in the Asia-Pacific as a whole. The results reflect the growing importance of the Chinese economy to the rest of the region, for most of whom, China is their largest trading partner. That the importance of the success of structural reforms in China is seen as the top factor influencing the future of growth in the Asia-Pacific echoes the finding that the top risk to growth is a slowdown in China.

Trade Liberalization in the Asia-Pacific

While respondents did not rank trade liberalization as a top factor for growth in their individual economies, it was the second most important factor for growth in the region as a whole. That is not to say that trade liberalization was considered unimportant; 57 percent of respondents did select it as being important or very important for their economies future growth, but a much more significant 69 percent thought further liberalization was important to very important for the growth of the region as a whole.

The Rule of Law

Improvements to the rule of law also ranked highly echoing the finding from the question on factors influencing growth in individual economies on the importance of policy reform and institutional quality.

Workforce Training and Mobility

Workforce training and mobility was seen a key factor for the future growth of the region, again, echoing the list of perceived risks to growth – where the shortage of available skills and talent was a top risk. This was a much more important factor for respondents from Southeast Asia who scored it at 4.1 – as important as the success of structural reforms in China.

The Future of Asia-Pacific Regional Cooperation

As APEC celebrates its 25th anniversary there are increasing questions about its future role. Its traditional agenda of trade liberalization is taken up by the various mega-regionals in the region and there are now other architectures that bridge the Pacific Basin.

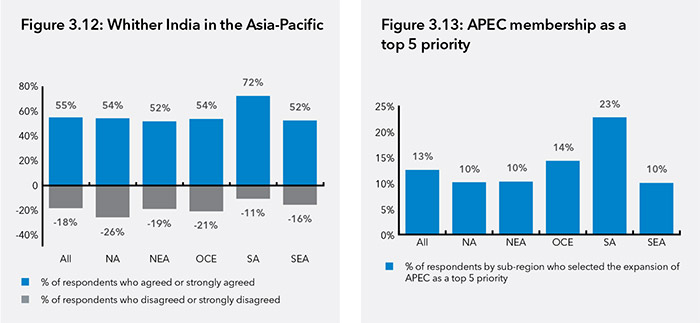

The question of India joining APEC has been at the background for a number of years. As with the results from previous years there was strong agreement that India should be a member of APEC. However, when all respondents were asked for priorities for APEC leaders, the issue of membership ranked extremely low: 19th out of 27 issues.

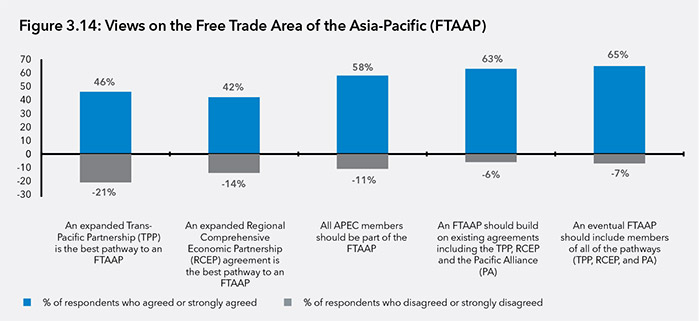

Towards an FTAAP

Although an FTAAP has principally been a concept espoused by APEC and related institutions, especially the APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC), there is little clarity on what the FTAAP is and who would be part of it. The 2010 APEC Leaders’ declaration stated: ‘An FTAAP should be pursued as a comprehensive free trade agreement by developing and building on ongoing regional undertakings, such as ASEAN+3, ASEAN+6, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, among others.’

Opinion-leaders showed no clear-cut preference for either route – the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) - and prefer the more agreeable but nebulous concept of building on other agreements including the TPP, RCEP and the Pacific Alliance. Chapter 2 of this report suggests some details on how this concept might work. It suggests that the RCEP and TPP negotiations may, if successfully concluded, provide way-stations toward the FTAAP – through new, regionally acceptable rules and also facilitate experimentation with and adjustment to deeper integration. However, by themselves, neither is likely to lead directly to an FTAAP and additional agreements are needed to achieve rules that encompass the Asia-Pacific region. The chapter examines an FTAAP umbrella agreement built around RCEP and the TPP, it argues that such an agreement could set relatively high standards, encourage liberalization across the region, and lead to a system of tiered rules for economies at different stages of development.

On the question of membership of the eventual FTAAP, generally there was agreement that all APEC members should be part of the FTAAP but there was even stronger support for the proposition that it should include members of all of the pathways. This raises the question of APEC membership for India, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar who are part of the ongoing RCEP negotiations, and Colombia which is part of the Pacific Alliance – if APEC is to play a significant role in guiding the development of an FTAAP.

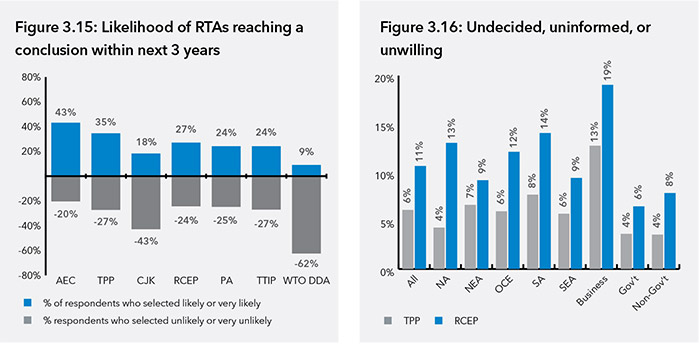

How likely are any of the regional trade deals to reach a conclusion?

Opinion-leaders were skeptical about any of the proposed trade deals in the region reaching a conclusion within the next three years. They were most optimistic about the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) with 43 percent thinking it was likely to reach a conclusion and 20 percent not likely. The AEC has a self-imposed deadline for completion by the end of 2015. Some 35 percent of respondents expected the TPP to reach a conclusion within the next three years, with 27 percent thinking it unlikely. The TPP has already missed a deadline at the end of 2013 but continues an intense series of negotiations. Furthermore, even if negotiations are concluded, in the case of the United States, the deal would need Congressional approval, a big hurdle given the lack of Trade Promotion Authority.

Ambivalence Reigns

In general, opinion-leaders were ambivalent about the likelihood of a conclusion within the next three years of many of the trade deals currently being pursued.

Just 27 percent of respondents thought it likely that a conclusion would be reached for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, involving the 10 members of ASEAN Plus economies with which it has existing trade agreements, namely, China, India, Japan, Korea, and Australia & Zealand with a deadline of 2015 for completion. The numbers were reversed for the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) involving the US and the EU with 27 percent thinking a conclusion unlikely and 24 percent likely.

Respondents were equally ambivalent about the Pacific Alliance involving Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru with 25 percent thinking a conclusion unlikely and 24 percent likely.

Respondents were most skeptical about the possible conclusion of the CJK involving China, Japan and Korea; 43 percent thought it an unlikely possibility and 18 percent likely.

While not a regional deal, WTO Doha Round remains something Ministers and Leaders continue to pay lip service to but opinion-leaders in this survey have all but given up on it with only 9 percent thinking a conclusion in the next three years likely.

Need for Outreach

These survey results are not gauging public opinion but those of the informed policy community but even amongst this group there was a proportion of respondents who selected ‘don’t know’ when asked if the agreements would be completed within the next three years – especially the business community. This could mean either that they don’t know enough about the agreement to make a judgment or simply don’t know about the agreement at all. It could also mean that they know a lot about the agreements, but feel unable to judge their political dynamics. No matter what the case, this casts a shadow over these mega-regional deals which are supposed to facilitate trade across the region.

While the TPP has received substantial media coverage and has completed at least 18 rounds of negotiations (more if counting some the other ‘mini-rounds’) as well as numerous ministers’ and chief negotiators’ meetings, a remarkable 13 percent of respondents selected ‘don’t know.’ With the RCEP, a much newer concept with a deadline of 2015, 19 percent selected ‘don’t know.’ Respondents were most unfamiliar or unwilling to make a judgment on the Pacific Alliance with 27 percent selecting ‘don’t know.’ The lack of familiarity with the PA bodes ill for those members who would like to see it considered as a potential pathway towards an FTAAP.

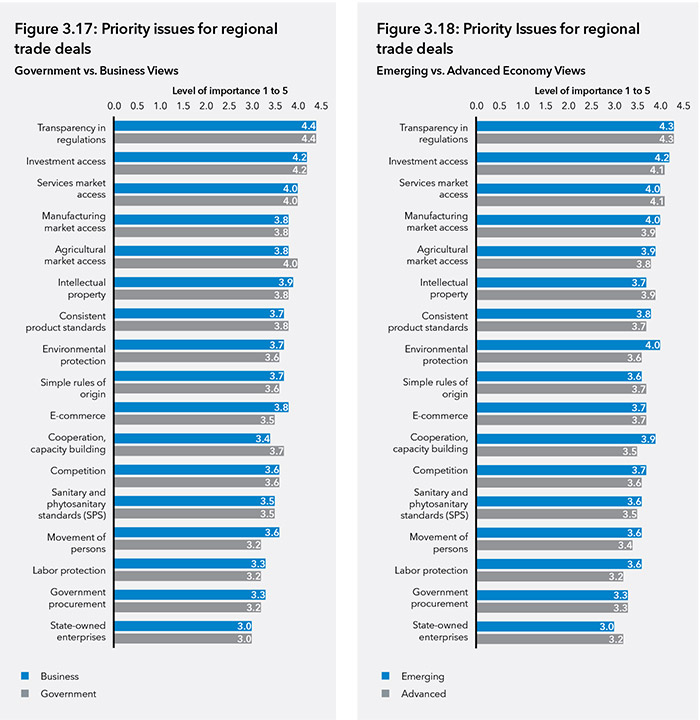

Priority Issues for Regional Trade Agreements

Respondents were asked to rate 17 issues in terms of their need to be addressed in Asia-Pacific trade agreements. The list of 17 issues broadly corresponds with the typical chapters in trade agreements such as the TPP and RCEP.

There was a remarkable degree of convergence between respondents from the business and government sectors in terms of priorities, at least among those who work on Asia-Pacific issues. The issues where the gap between government and business were highest were:

- Movement of persons

- Agricultural market access

- Cooperation, capacity building

- E-commerce

- Consistent product standards

Business respondents rated the ‘movement of persons’ and ‘e-commerce’ higher than government, while government respondents rated ‘agricultural market access,’ ‘cooperation and capacity building,’ and surprisingly, ‘consistent product standards higher’ than their business counterparts.

One of the challenges for Asia-Pacific integration is the diversity in levels of development; even though there was some convergence on priorities, there were some significant and interesting differences. The areas with the highest divergence between emerging and advanced economies were:

- Environmental protection

- Cooperation, capacity building

- Labor protection

- Movement of persons

- State-owned enterprises

These differences were not intuitive; for example, respondents from emerging economies rated environmental and labor protections higher than their counterparts from advanced economies. Not surprisingly, ‘cooperation and capacity building’ were a higher priority for those from emerging economies as was movement of persons, while ‘state-owned enterprises’ was a higher priority for advanced economies.

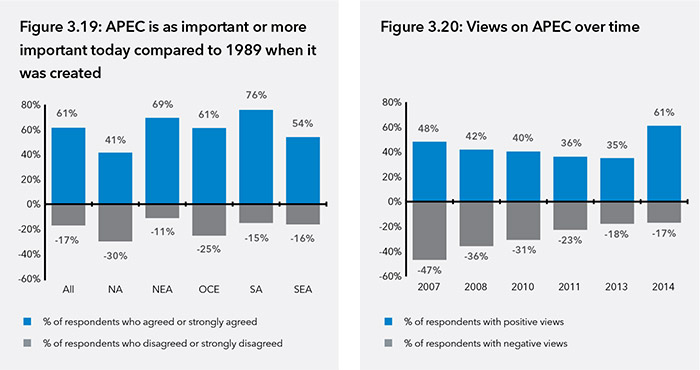

The Future of APEC

On the occasion of APEC’s 25th anniversary, there are questions being asked about the future role of what has been the region’s pre-eminent regional institution, and until the creation of the East Asia Summit, the only forum where the leaders of the region’s major economies would meet on an annual basis.

When PECC started the survey in 2007, views on APEC were at best ambivalent. Some 48 percent of respondents had positive view of APEC and 47 percent negative. Over time the negative sentiments towards APEC have been decreasing but so had positive sentiments, until this year when APEC had a strong positive approval of 61 percent and only 17 percent negative.

Southeast Asians More Positive on APEC

Part of the reason for this shift, is the increased positive sentiments towards APEC from Southeast Asian respondents. In PECC’s 2013 survey, only 26 percent of opinion-leaders from Southeast Asia expressed positive views towards APEC with 25 percent having a negative view compared to this year with 54 percent having positive views and only 16 percent negative. Indonesia’s hosting of APEC in 2013 could be a reason for this shift, especially due to the strong emphasis in last year’s agenda on infrastructure and supply side constraints which are clearly issues of great concern to the region’s emerging economies, especially those in Southeast Asia.

North American Ambivalence

Of concern perhaps is the ambivalence among opinion-leaders from North America towards APEC; 41 percent of respondents had positive views and 30 percent negative. While still a net positive, it is far from a ringing endorsement, but it is an improvement from 2013 when only 30 percent of respondents from North America had a positive view of APEC and 22 percent negative.

APEC’s Importance for South America

Respondents from South America remain by far the most positive towards APEC with 76 percent having positive view and 15 percent negative. While many members of APEC now have alternative architectures for broad engagement with the Asia-Pacific, APEC remains the only one for Pacific Rim South American economies to engage with their counterparts in the rest of the region.

APEC: New Challenges and Agenda Ahead for Asia-Pacific Cooperation

The findings of this survey indicate the broad range of challenges facing the Asia-Pacific. It is clear that the regional policy community remains extremely concerned about the implementation (more lack thereof) of the reforms needed to keep growth momentum high. This is evidenced by the types of risks to growth identified such as the failure to implement structural reforms as well the factors identified as being critical to future growth prospects – policy reform, i.e. improvements in institutional quality and regulation.

While APEC has addressed many of these issues through its work on structural reform and the Growth Strategy, opinion-leaders are not satisfied with the actions taken thus far. Next year’s assessment of the strategy provides an opportunity to review what has been done and to consider next steps. By then it will be clear what commitments G20 members will have made, and how APEC members might respond.

In the 20 years since the Bogor Goals were set, the number of regional trade agreements has proliferated and APEC has yet to fully come to terms with what this means for its mission and its modalities. Clearly the concerted unilateralism that characterized its earlier phase has been replaced by competitive liberalization. In setting the Bogor Goals, APEC Leaders also emphasized their ‘strong opposition to the creation of an inward-looking trading bloc that would divert from the pursuit of global free trade.’ The challenge APEC faces is in ensuring that the current spate of mega-regionals are not exclusive, but building blocks for regional and global free trade.