CHAPTER 1: ASIA-PACIFIC ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

Contributed by Eduardo Pedrosa

Prospects for Growth

In the year and a half since the global pandemic started the Asia-Pacific economy has undergone an extraordinary decline but is set to post a sharp recovery this year thanks to unprecedented policy support and the remarkable innovation and manufacture of vaccines.

Forecasts

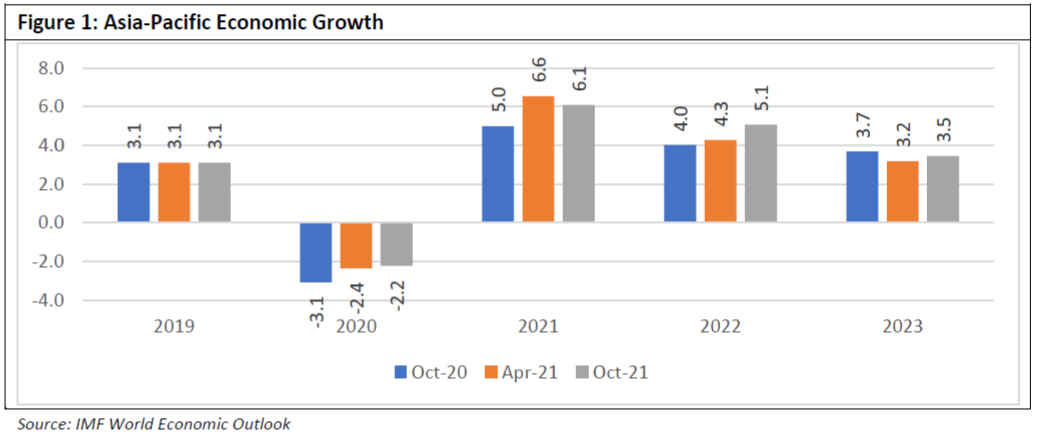

The region is expected to grow by 6.1 percent in 2021 and 5.1 percent in 2022 (see Figure 1). While all economies are expected to bounce back from last year’s nadirs, the robust recovery this year comes largely from those economies in the region that have been able to move ahead with vaccinating a large portion of their populations notably China and the United States.

Due to their economic weight and relatively rapid recoveries from the crisis they are expected to account for 72 percent of the region’s growth this year. The estimates for the recovery are significantly better than the 5.0 percent and 4.0 percent growth for 2021 and 2022 respectively made at this time last year (see Figure 1) largely due to the magnitude of the stimulus measures as well as the accelerated pace of vaccination in a few economies. However, while expected growth for 2021 has been downgraded since April due the resurgence of the pandemic as well as supply side constraints, much of this is expected to be made up in 2022 with an improved economic forecast for regional economic growth of 5.1 percent compared to earlier expectation of 4.3 percent.

It is also the nature of a pandemic shock where economies are temporarily shut down to stymie transmission and then re-opened. This recession is where the taps are turned off by lockdown and closed borders, and the waters of economic activity flow again quickly when the taps are turned on so long as there is no structural damage. The imperative for governments is to enable, and not impede, recovery.

The top risk to growth remains the pandemic. PECC’s annual survey of the regional policy community (run from 12 August to 17 September) reveals an unambiguous message that dealing with the Covid-19 crisis must be a priority and also believe that time is ripe to work out how to safely open borders to travel. This was not just identified as a top issue for dealing with the ongoing pandemic and its economic consequences but also as a top issue for APEC Leaders to discuss when they gather in November.

At the outset of the pandemic the discussion was whether the shape of the recovery would be v, w, or u shaped, a new letter has entered into the lexicon of economic literature ‘the k-shaped recovery’ signaling the divergent pathways that economies and societies are exiting from the crisis.

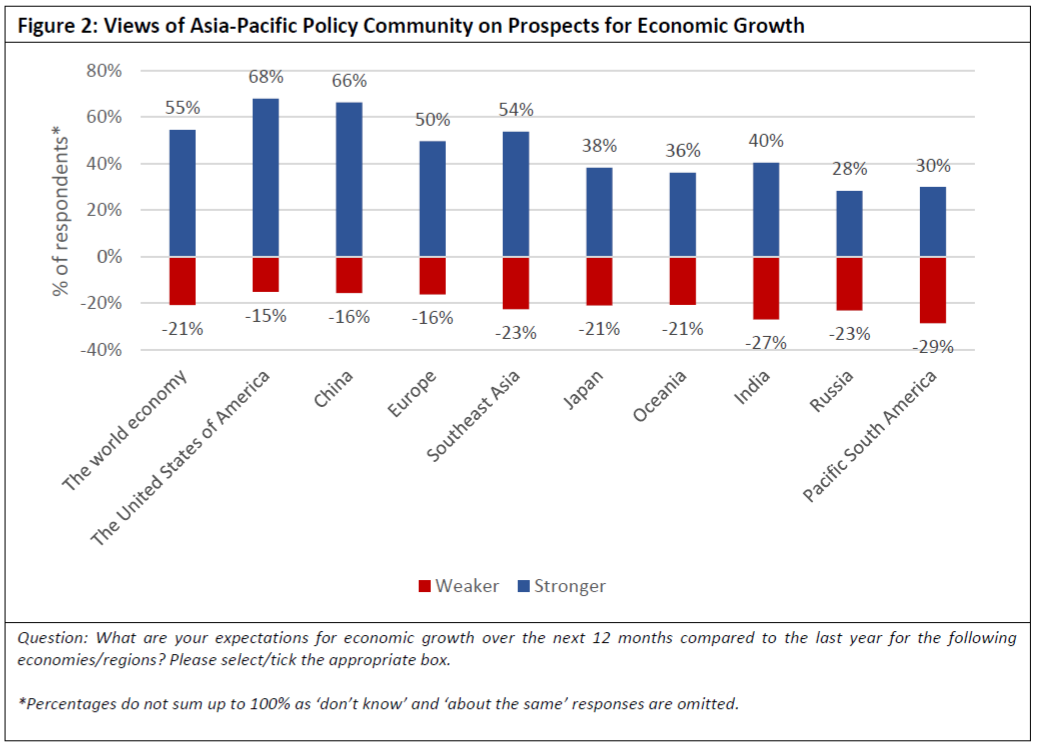

As the world emerges from the recession caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, our survey respondents’ views mirror forecasts of diverging growth patterns with most decidedly much more optimistic about the prospects for growth in those economies that had higher vaccination rates at the time of the survey – the United States and China (see Figure 2). This underscores the urgency of the equitable distribution and delivery of vaccines across the region and the world in order to improve the prospects of slower growing economies and strengthen robust Asia-Pacific and global growth.

While this may sound much more optimistic than most reports, some context is needed. Last year, in August 2020, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) assessed the global manufacturing capacity for Covid-19 vaccines, and from a survey of 113 vaccine manufacturers, estimated that the global capacity to produce COVID-19 vaccines through to end of year 2021 was between 2-4 billion doses.

Recalling the target set by CEPI in 2020 to distribute 2 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccine by the end of 2021 with a target of 20 percent of the population, as of the beginning of October, about 30 percent of the eligible global population has been fully vaccinated or some 6.4 billion doses have been administered – at a rate of 28.9 million a day. This is a testament to the ability of the global manufacturing and trading systems to deliver during an emergency. The problem, however, has been that vaccination rates are uneven, with Asia at 39 percent, South America at 42 percent, North America at 48 percent, Europe at above 50 percent but Africa at less than 5 percent.

Risks to Growth

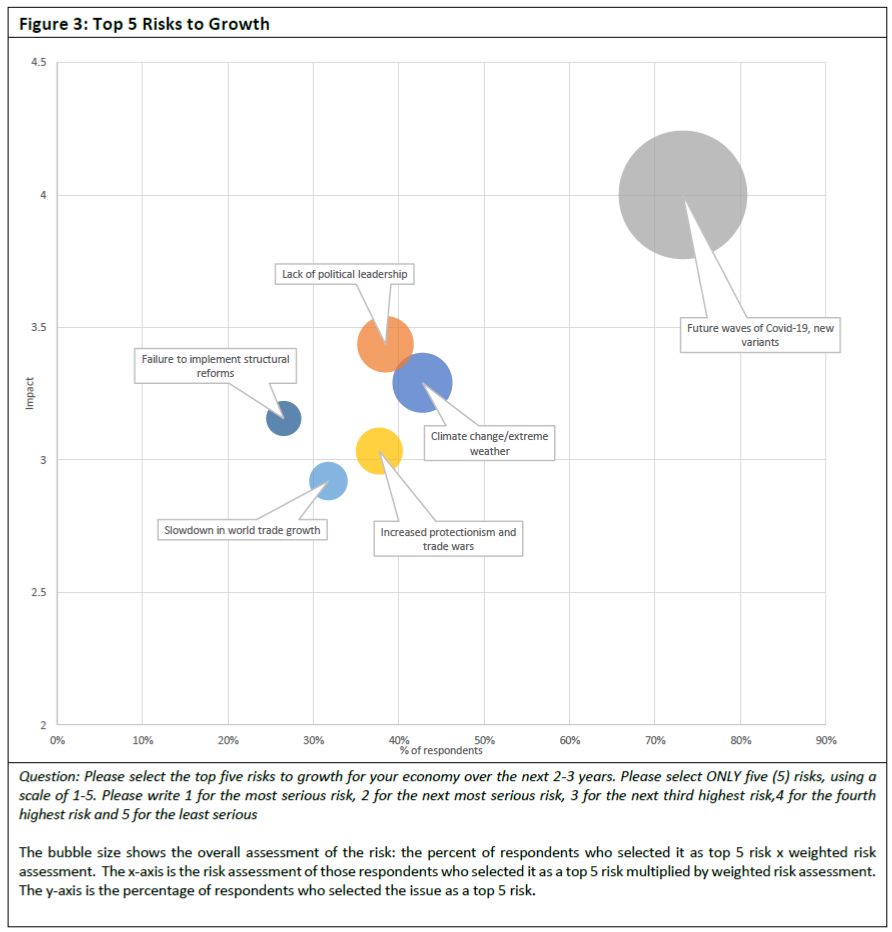

The potential for future waves of COVID-19 while there are still large unvaccinated populations and new variants is by far the most important risk to growth as perceived by survey respondents. However, others also matter. The top 5 risks to growth over the next 2-3 years selected by respondents are shown in Figure 3. In addition to pandemic risks they include the following:

- Climate change/extreme weather

- Lack of political leadership

- Increased protectionism and trade wars

- Slowdown in world trade growth

- Failure to implement structural reforms

The perceptions of these risks are likely related in some way. Respondents are concerned about climate change and its consequences as well as the capacity to design and drive the economic reform programs needed to ‘build back better.’ Regional cooperation can play a useful role in mitigating these risks, capacity building where needed, and building confidence in the direction of reform.

Concerns Over Future Waves of Covid-19

The central risk to the outlook continues to be the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, especially the emergence of new variants. According to the World Health Organization ‘when a virus is widely circulating in a population and causing many infections, the likelihood of the virus mutating increases”1 therefore the faster the world can stop the spread of the virus globally the less likely variants will emerge.

This was strongly affirmed by findings of our survey. Health pandemics were the top risk to growth in last year’s survey and continue to dominate the policy community’s concerns for the next 2-3 years. This was equally shared across all sub-regions and stakeholder groups, with 73 percent of respondents selecting it as a top 5 risk to growth for their economy.

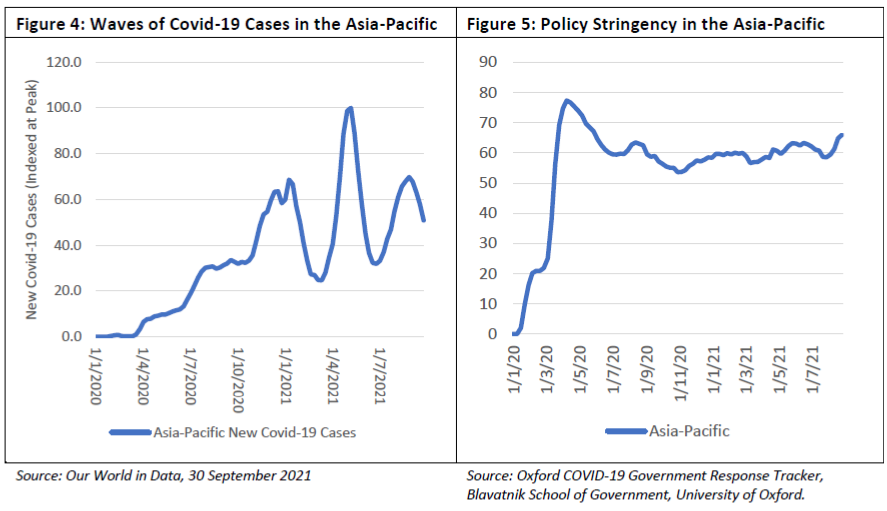

While the number of new Covid-19 cases in the region peaked in May 2021, a new wave hit the region in July and August (Figure 4). This wave largely caused by the more contagious Delta variant also affected some economies in Southeast Asia and East Asia, that had previously managed to cope relatively well with the pandemic and impacted regional supply chains.

These waves have occurred in spite of a consistently ‘stringent’ policy regime in the region (Figure 5) to contain the spread of the pandemic through non-pharmaceutical interventions such as the closing borders, implementing work from home policies, shutting and curtailing public gatherings.

In last year’s survey we asked respondents what were the factors they thought should be taken into account for exiting from lockdown. The top 3 were:

- Sufficient medical capacity to deal with expected number of cases (including hospital beds, doctors and nurses, personal protective equipment, and medical supplies)

- Evidence that the number of new cases is reducing

- The development of a vaccine2

These findings mirrored analysis from those who studied ‘non-pharmaceutical interventions’ who stressed that the goal was to mitigate the spread of the virus and prevent healthcare systems from being overwhelmed.

“The major challenge of suppression is that this type of intensive intervention package – or something equivalently effective at reducing transmission – will need to be maintained until a vaccine becomes available (potentially 18 months or more).3

Vaccines did become available in less than 18 months but the problem has been the emergence of variants (the delta variant emerging in a mostly unvaccinated developing economy), their unequal distribution across the world, and the refusal of some populations in richer economies to become vaccinated despite the availability of vaccines.

This underscores the need for international cooperation. An IMF policy paper put forward a proposal to: (1) vaccinate at least 40 percent of the population in all economies by the end of 2021 and at least 60 percent by the first half of 2022, (2) track and insure against downside risks, and (3) ensure widespread testing and tracing, maintaining adequate stocks of therapeutics, and enforce public health measures in places where vaccine coverage is low. 4

The estimated cost of the proposal was US$50 billion which the authors compared favorably against an estimated US$9 trillion benefits the implementation of the measures would bring. PECC urges APEC, which is home to 38 percent of the world’s population, to take note of this proposal and support it.

Two-Speed Recovery

The proposition of a K-shaped recovery is linked to different patterns of success in the application of vaccines. By our estimates based on IMF forecasts, economies with current vaccination rates above 30 percent rates as at 1 September 2021 are expected to recover from the crisis at a faster pace and grow by 6.3 percent in 2021 compared to 5.4 percent growth of those with vaccination rate currently below 30 percent. The recovery is expected to become more broad-based across the region as vaccines become more widely available in 2022.

The K-shaped recovery is also evident within economies. For example, within the United States while growth has been strong in 2021 and employment rates have rebounded past pre-COVID-19 levels for high-wage workers, they remain significantly lower for low-wage workers, with employment rates still 25.6 percent lower for those earning less than US$27,000. 5 While those circumstances may be unique to the United States, there is a fairly strong correlation at the industry level with jobs in leisure and hospitality down 7.8 percent.

The International Labor Organization estimates that in 2020 the equivalent of the hours worked by 255 million full-time workers were lost. Much of the income loss fell disproportionately on lower income groups.6 While the recovery is expected to create new jobs, there are risks that many of these will be in higher skills categories further exacerbating the K-shape of the recovery. The ILO’s model estimates bear out those at the economy level with an estimated 13 percent global drop in employment in the accommodation and food section. 7

A key economic concern arising from K-shaped recoveries, is the risk of tightening financial conditions. Some economies are recovering quickly and face inflation pressures, aggravated by supply chain bottlenecks, while others are improving at a much slower pace due to much lower vaccination rates. Markets are carefully watching signals from the US Federal Reserve (Fed) for any indication of when interest rates might rise. The IMF has been at pains to warn of the potential of a repeat of the ‘taper tantrum’ which occurred in 2013 when bond prices crashed (they have an inverse relationship) and equity markets slumped more than four per cent in three days after the then-chairman of the Fed raised the prospect of tapering its QE program, that is, slowing down its bond purchases. Following the subsequent rise in interest rates, emerging markets suffered from capital flow reversals. There are current fears of a re-run. IMF Chief Economist, Gita Gopinath warned in an interview with the Financial Times that

“[Emerging markets] are facing much harder headwinds…[T]hey are getting hit in many different ways, which is why they just cannot afford a situation where you have some sort of a tantrum of financial markets originating from the major central banks”.8

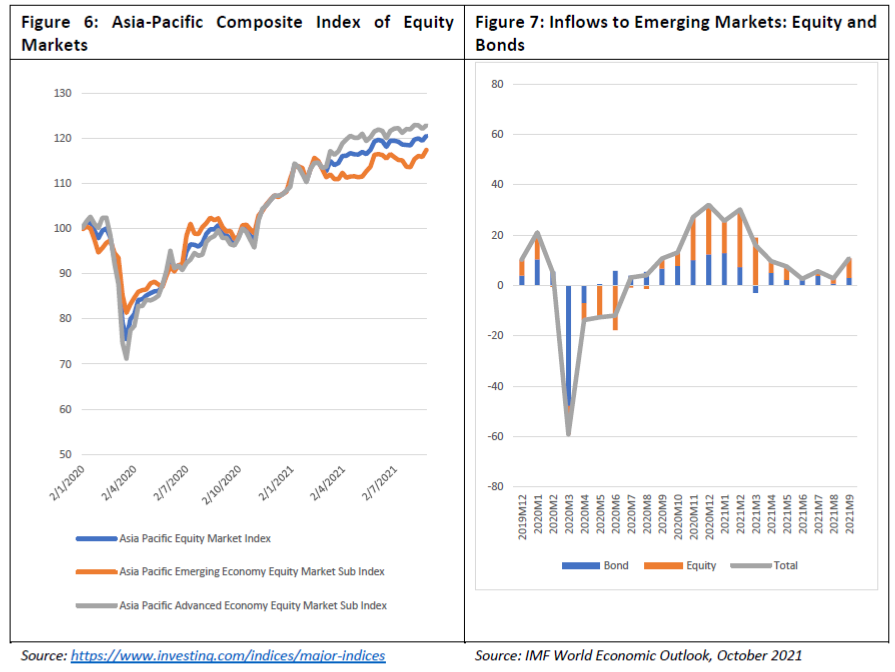

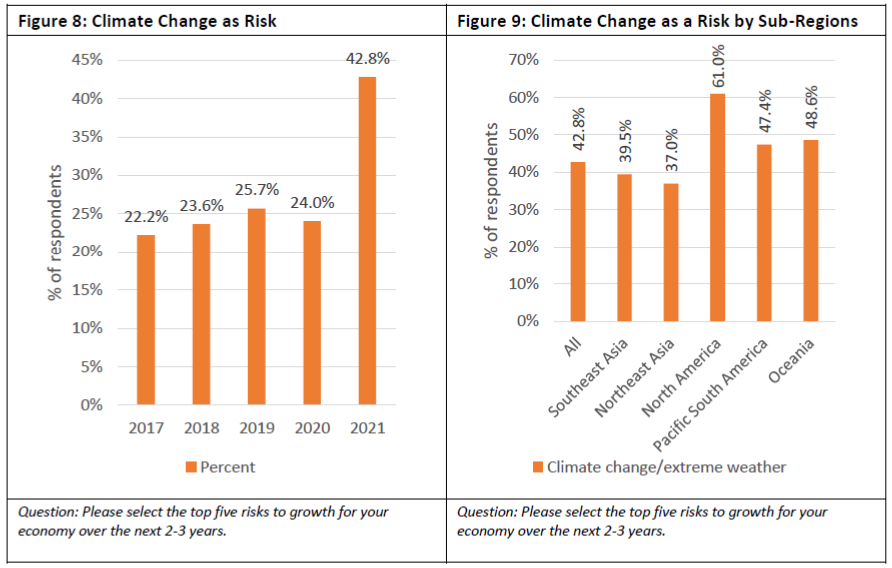

To date, both advanced and emerging market Asia-Pacific equity markets have moved in lockstep (Figure 6) responding to broader macroeconomic concerns over the course of the pandemic. The steep drop seen in the first quarter of 2020 has been followed by a strong bull run in equity markets largely due to the unprecedented injections of liquidity into the financial system by central banks. Across the Asia-Pacific the GDP-weighted index of equity markets is up 20 percent since the start of the pandemic. Advanced economy equity markets are up slightly higher by 21 percent, while emerging economy markets equity markets are up by 17 percent as at the end of August 2021.

As shown in Figure 7, portfolio inflows to emerging markets have remained robust throughout the pandemic period. There was some slowdown of flows from May to August but they picked up again in September 2021.

Debt Servicing

While no pressures are immediately evident, the US Federal Reserve has indicated that it may begin the process of tapering its easy monetary policy by the end of 2021. While markets interpreted the news positively, memories in the region will be fresh of the ‘taper tantrum’ in 2013, and there remain risks of reversals of capital flows and exchange rate depreciations.9 While markets have been relatively stable throughout the pandemic, they have recently been subject to volatility uneasy. There were significant differences between PECC survey emerging and advanced economy respondents on this issue, with 70 percent of emerging economy respondents rating this as an important or very important issue compared to 49 percent of those from advanced economies.

The G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors meeting in July welcomed the progress under the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), undertaken in April 2020 to assist developing countries struggling debt servicing during the pandemic. The G20 is undertaking an Independent Review of Multilateral Development Banks’ Capital Adequacy Frameworks and the IMF has increased SDRs by an equivalent of US$650 billion to increase global liquidity. However, only one APEC member is part of the DSSI.

While economic activity has recovered, borders are only gradually being opened in the Asia-Pacific due to continued concerns over the spread of the Covid-19 virus and differential rates of vaccination across the region. This has significant consequences for the travel and tourism sector, including business travel, which accounts for large parts of regional economies but also knock-on implications for regional supply chains constraining fleet capacity of air cargo.

Climate Change as a Risk to Growth

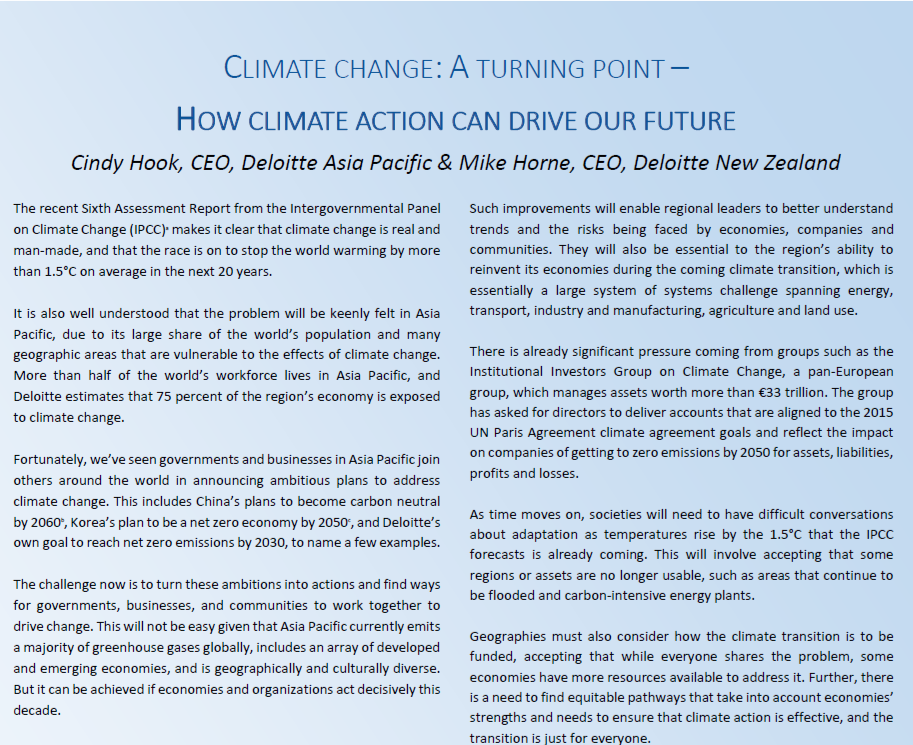

The second most frequently selected risk to growth in this year’s survey was climate change/extreme weather events, with 43 percent of respondents selecting it as a top 5 risk to growth for their economies (Figure 8). This is a huge increase from previous years when roughly 25 percent of respondents selected climate change as a risk to growth for their economies. It may in part be because the thematic focus of this year’s report is on climate change, or the timing of the survey happened to coincide with the release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC’s) 6th Assessment report10 which warned of “widespread, rapid, and intensifying climate change.” Or it may simply reflect growing awareness of the economic consequences of climate change as a consequence of increased evidence and greater incidence of devastating climate change-related events including storms, fires, and heat records.

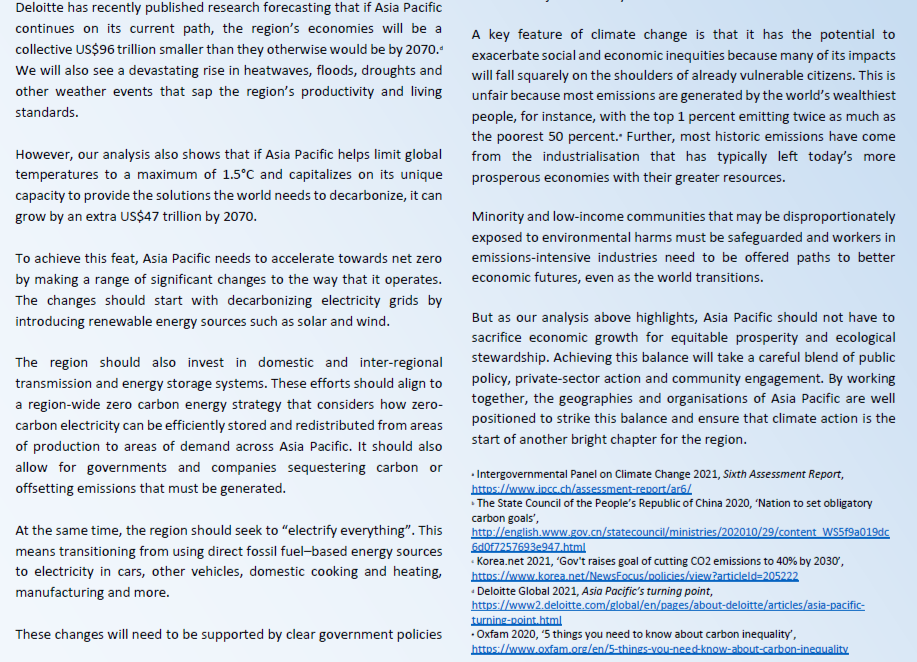

There were significant differences between sub-regions on the perception of climate change as a risk to growth (Figure 8) with more North American respondents selecting it as top5 risk to growth, compared to other parts of the Asia-Pacific. What drove the relatively large percentage of respondents selecting climate change were relatively higher numbers from Northeast and Southeast Asia. Although larger percentages of North American respondents selected climate change as a risk as seen in Figure 8, due to the larger number of Asian economies and respondents the overall response reflects that reality.

Climate change issues will be discussed in more depth in Chapter 2.

Lack of Political Leadership

A lack of political leadership was once again a top 5 risk to growth. Overall 38 percent of respondents selected it as a risk to growth, up from 33 percent last year. The most concerned were respondents from Southeast Asia, Oceania and Pacific South America.

This is a little different from last year when respondents from North America and Pacific South America were the most concerned. It is difficult to know what exactly respondents were concerned about with respect to the perception of lack of political leadership. One common correlate among Southeast Asian and Pacific South American respondents was a concern about a failure to implement structural reforms. It could also be connected more generally to economies responses to common issues such as the response to Covid-19, which was a common top-5 risk across all sub-regions.

Increased Protectionism and Slowdown in Trade Growth

Concerns over protectionism and a slowdown in trade growth remained high among the regional policy community. This has been a top risk to growth for many years reaching a peak in 2019 when 64 percent of respondents selected it as a top 5 risk to growth for their economies.

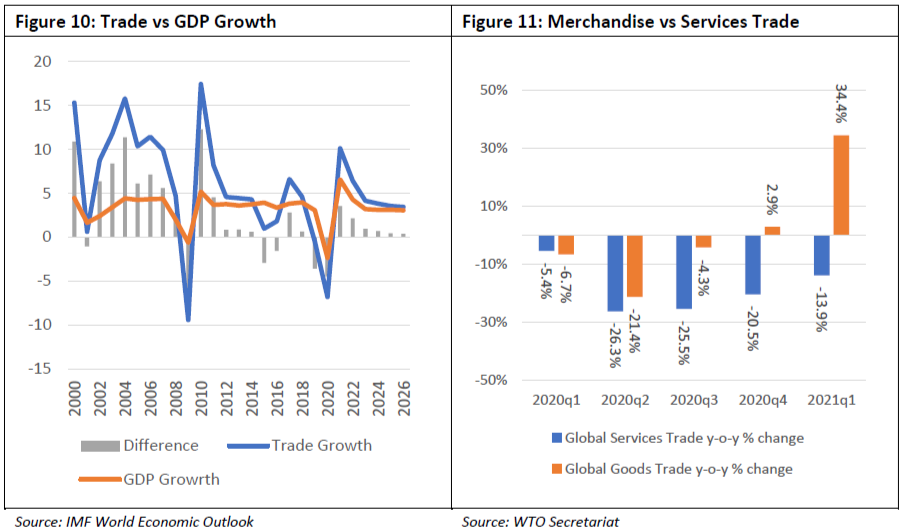

Concerns over slowing trade are similarly long-standing in a region where growth has been driven by trade for many years. Although trade momentum is returning, the differential between trade and overall growth in aggregate demand is significantly less than what it was during the 1990s and 2000s when growth in global value chains and unbundling was a significant driver for the region. (Figure 10)

Global merchandise trade recovered during the 4th quarter of 2020 growing by 2.9 percent (Figure 11). The WTO Secretariat is expecting it to grow by 8 percent this year and about 4 percent in 2022. Trade in commercial services continues to lag behind, and trade in travel services, which make up 11 percent of commercial services trade was down by 63 percent and not expected to recover for some time.

While the WTO does see recovery in some services sectors especially in financial transactions, others lag far behind11. This further compounds the imbalanced nature of the recovery. While some sectors have been able to digitize and deliver services directly via Mode 1 (a service supply from one territory into the territory of another). Others such as tourism and restaurants that depend on face-to-face interactions cannot. The WTO notes this is situation differs from the recovery from the Global Financial Crisis when services trade was more resilient than goods trade.

Analysis by the WTO finds that ‘trade policy restraint by WTO Members has prevented a destructive acceleration of trade restrictions that would have further harmed the world economy’; 35 percent of the measures taken by its members since the crisis could be considered restrictive of goods trade. Of great concern is that over time, about 9 percent of world goods imports has become subject to some form of trade restrictions. On services, WTO members introduced 122 measures unrelated to the pandemic affecting trade in services during the review period, targeting different modes of supply across various sectors – some of which were trade restricting. 12 In other words, respondents are rightly concerned about rising protectionism.

Inflation as a Risk to Growth

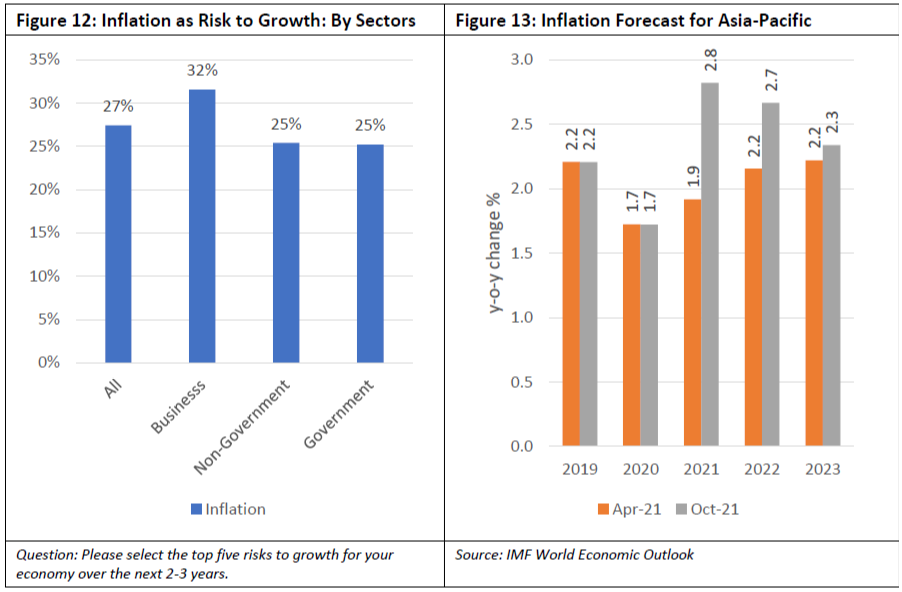

A significant number of survey respondents refer to inflation as a risk to growth (Figure 12). Overall, inflation was the 7th highest risk in survey, but for business respondents it was the 5th highest risk to growth. It may well be that the businesses are feeling the impact of price increases before the rest of community. There is some debate over the nature of the current inflationary pressures – whether there is a risk of ‘jumping at shadows’. Underlying the difficulty in reaching any conclusion is that there remains significant capacity in the economy with the solution coming from fixing supply and relaxing restrictions on the movement of people as and when health circumstances permit.

Central banks are carefully watching price increases and debating whether they are a transitory phenomenon caused by exceptional circumstances that will fade as conditions normalize or are the result of more fundamental changes in supply-demand conditions.

Some of the underlying factors complicating the picture are base effects of the considerable decreases in economic activity last year13; the surge in demand for some consumer durable products during the; bottlenecks in the production of intermediate goods, the impact of weather on food staples; and the constraints in the transportation system.

Chile, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Russia, and Singapore’s central banks have raised interest rates in the face of differing pressures. Figure 13 shows both the April forecasts for inflation as well the most those made in October. These demonstrate almost 1 percentage point increase in inflation expectations for the region.

While circumstances differ enormously within individual economies hence making it difficult to make any generalized conclusions, it is worth keeping front of mind the tremendous supply shocks that the region has and continues to suffer largely as a result of the pandemic. Raising the cost of money is not going fix supply, produce more semi-conductors, nor will it bring people back to work, it does however potentially risk stalling what is really needed – investments in people and plants. The critique provided by Goodhart “In the post-Global Crisis period, central banks injected money into the financial system. Financial institutions, needing to strengthen their balance sheets, found buying financial assets a far more reliable route to achieving that protection than lending to the private sector”14. As a result, those injections found their way into the monetary base rather than broad money or credit. As discussed elsewhere in this report capex was perennial disappointed prior to Covid, but the signs are that this is shifting with the corporate sector now feeling ‘optimistic’ and willing to invest. If the velocity of money has collapsed there may well be structural if not misaligned incentives that need to be addressed through structural reforms.

What’s Driving Higher Prices?

The underlying factors of the price increases needs to be broken down into various components:

- Demand surges amidst factory closures due to Covid-19

- Temporary closures of ports due to Covid-19 infections in ports

- Shortage of workers due to Covid-19

- The temporary Suez Canal blockage

- Policy restrictions

Demand Surge

As economies went into lockdowns in the second quarter of 2020 it changed the pattern of domestic consumption in many economies. There was an initial surge in demand for information technology products for home-based school and work – laptops and computers. This came exactly at the time when key manufacturing hubs in Asia had to temporarily shut down due to the pandemic or faced labor constraints due to policy shut-downs.

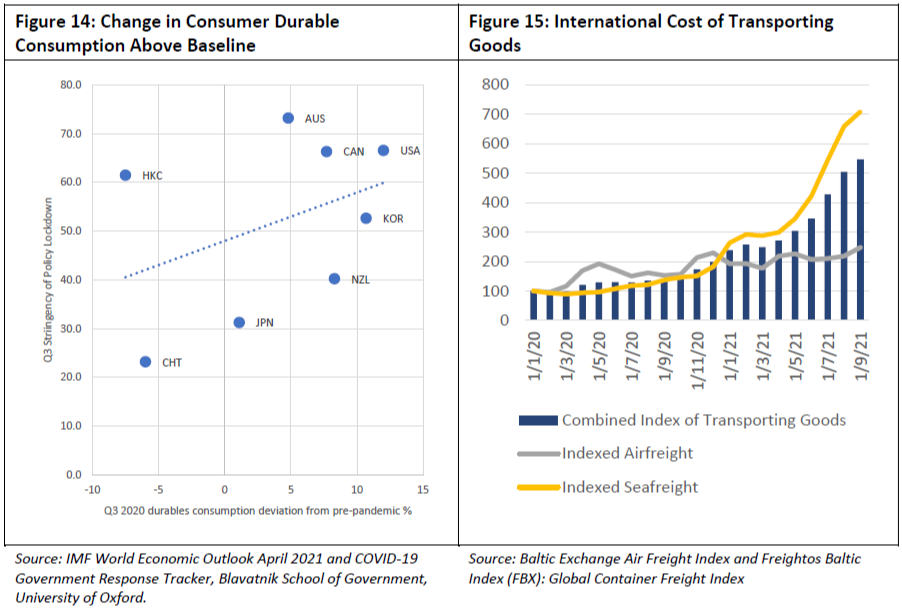

Average consumption of consumer durables was on average 9 percent higher among the region’s advanced economies during the 3rd quarter of 2020 but higher for some economies – for example 12 percent in the United States. (See Figure 14). During his speech at the Jackson Hole Symposium, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said that “Spending on durable goods has boomed since the start of the recovery and is now running about 20 percent above the pre-pandemic level.”15 The data in Figure 14 shows only the data up to the end of the third quarter of 2020.

While not common to all economies, the more stringent the lockdown, the consumption of consumer durables has tended to run above pre-crisis baselines. With the exception of Hong Kong, China and Chinese Taipei, consumer durable consumption in the region’s high-income economies was above the pre-trend average and more so depending on the stringency of the lockdown measures.

Analysis by the European Central Bank based on the rise in shipping costs (Figure 15) over the course of the pandemic have not been the result of a single factor. The initial rise at the beginning of 2020 came as a result of the supply sharp curtailing of transport systems (eg limits on crew changes and port operations) then, as these began to be addressed, the surge in demand became the primary cause especially at the end of 2020.16 They argued that “However, as supply adjusts to increased demand, these bottlenecks should delay but not derail the global recovery.”

However, since the end of 2020, global trade has been hit by a series of incidents that have further constrained capacity. In March 2021, the container ship the Ever Given was blocked the Suez Canal for 6 days causing an estimated US$230 billion cost to international trade. In May, Yantian Port temporarily suspended operations due to the discovery of Covid-19 cases.17 In August, Ningbo also suspended one of its terminals due to a Covid-19 case. 18 In the United States Los Angeles and Long Beach Ports report long queues of ships waiting to unload.19As of July 2021 over 116 ports around the world reported congestion, with 328 ships waiting to unload their cargo.20

The initial policy restrictions and grounding of air travel caused a 98 percent drop in international air passengers and with it an 80 percent drop in ‘belly capacity’ due to the decline in overall flights. Since then, air freight has been filling an urgent need to transport medical supplies and e-commerce fulfilment with commercial airlines using passenger aircraft for cargo-only flights.21

Pre-crisis prices of air freight per kilo were about US$3, since then they have spiked to above US$8.22 The picture is even worse for maritime, the Freightos index of container shipping prices shows an increase from US$1,500 to above US$11,000. A combined index of air and maritime freight prices at a 35-65 ratio, shows an enormous average increase in the cost of transporting goods over the period of the crisis. Taking both air and sea freight costs into account the average cost of transporting goods across the world has increased by 500 percent over the course of the pandemic. The most recent prices as the beginning of October show a decline in the average price of containers from US$9,949. It is not just price but availability and delays, some large retailers, in order to meet demand for the Christmas season have chartered their own cargo ships. 23

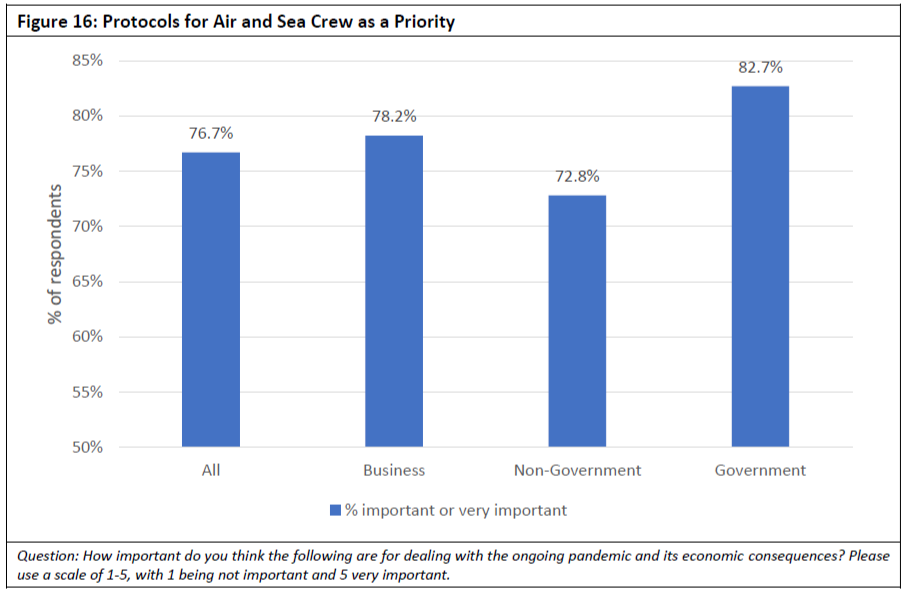

Since the onset of the pandemic, APEC Ministers and Leaders have continually emphasized the need to facilitate the flow of goods and services – this must include addressing how goods actually move across the world – by road; rail; sea; and air. Options available to APEC in this respect are discussed in the next part of this chapter. The second highest priority for dealing with pandemic and its economic consequences (discussed in the following section) was “protocols to facilitate the safe international movement of people starting with those involved in logistics and supply chains – aircrew and seacrew”. This was second only to the scope and pace of vaccination with 77 percent of respondents ranking it was important to very important. This issue was seen as important by all stakeholder groups, but especially so by government officials with 83 percent of them selecting it as an important or very important issue to deal with.

Views are divided on whether this is a temporary phenomenon or whether it will have lasting ramifications for how the corporate sector reshape global value chains. The rise in shipping costs was also found to be a central issue in supply challenges in analysis earlier this year by Goldman Sachs which came to the conclusion that ‘because supply challenges are largely driven by transportation and not production constraints—unlike last spring when supplier delays spiked due to factory shutdowns that halted the supply of intermediate goods—we expect that supply constraints will put upward pressure on prices but have less of an impact on real economic activity.’24 Their estimate back in March was that total shipping costs make up about 3 percent of the final cost of manufacturing output and international shipping costs less than 1 percent in the United States.

However, HSBC estimates that a 205 percent rise in container shipping costs over the past year could raise producer prices by up to 2 percent in the Eurozone.25 UPS which sees large volumes of air cargo warns that there will be lasting scars. “There’s an understanding that reliance on stretched supply chains puts you at risk,” Scott Price, president of UPS International told the Financial Times.26

The boom in demand for consumer durables came at the same time as a series of events impacted the ability of supply chains to respond to them. On top of new waves of Covid-19 induced factory shutdowns in manufacturing locations such as Malaysia and Vietnam, a fire at a plant in Tokyo27 and droughts in Chinese Taipei28 have been cascaded through supply chains impacting car manufacturing. Leading car manufacturers, Ford, General Motors and Toyota have all announced reductions to their global productions due to shortages in key components. 29 Auto makers are not the only ones facing problems – Sony and Microsoft launched their new products in December 2020, but they have faced supply chain issues and have been unable to keep up with demand – these shortages are expected to continue into 2022. 30

Impact on Inclusive Growth Goals

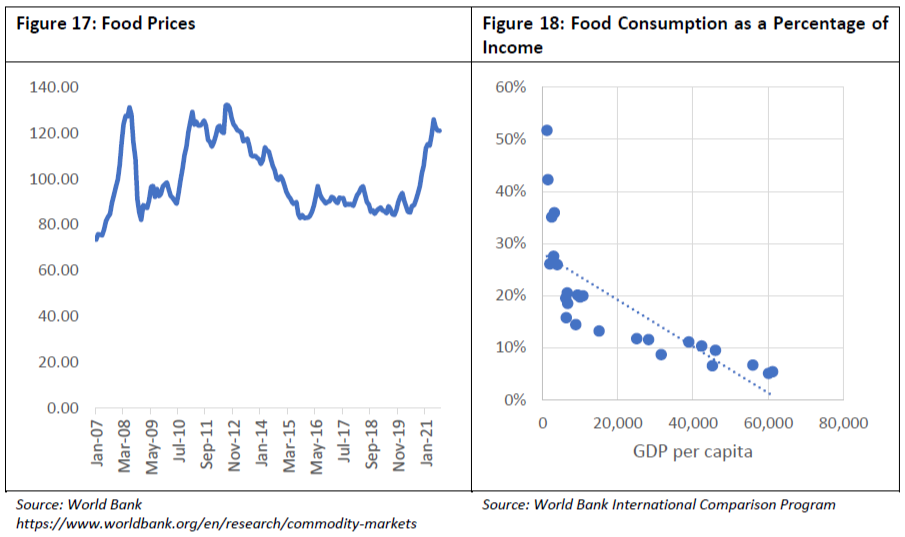

The rise in prices has not been limited to consumer durables. A worrisome dimension has been rising food prices. Food prices have consistently trended higher over the pandemic period, as of August 2021, they were 28 percent higher than at the start of 2020 (Figure 17). The reasons behind this are complex. Weather conditions in key cereal producers have resulted in poor supply for some commodities pushing prices higher but also underlying the higher food prices has been the surge in shipping costs.31

The impact of rising food prices will be felt very differently across as well as within economies with food consumption as a percentage of income considerably higher for low-income families. At income levels above US$40,000 food expenditure is less than 8 percent of household consumption expenditure, but at income level less than US$10,000, it is on average 27 percent of annual consumption. (Figure 18)

Fertilizer has seen a very significant rise in price. On average the price of fertilizers has risen by 85 percent since the start of the crisis. Underlying this are the same issues as in other goods – constrained production capacity due to Covid-19 restrictions affecting the supply chain but also surges in demand as well as trade policy issues32.

Very timely this year APEC adopted “Food Security Roadmap Towards 2030” which focuses on identifying actions and targets which APEC economies will pursue together to achieve food security in the region. While taking an inclusive and sustainable approach to food security, the roadmap includes among its action areas the promotion of public-private investment in infrastructure and cold chain to reduce the current levels of food loss and waste. Progress will be periodically reviewed.

While the language of the roadmap was focused on looking at food loss and waste along the food supply chain, it is timely to establish baselines and to explore the reasons why food prices have increased significantly during the pandemic. This is an especially important to ensuring that future growth is indeed inclusive given the relatively high proportions of income that the less-well-off spend on food.

Debt Dynamics

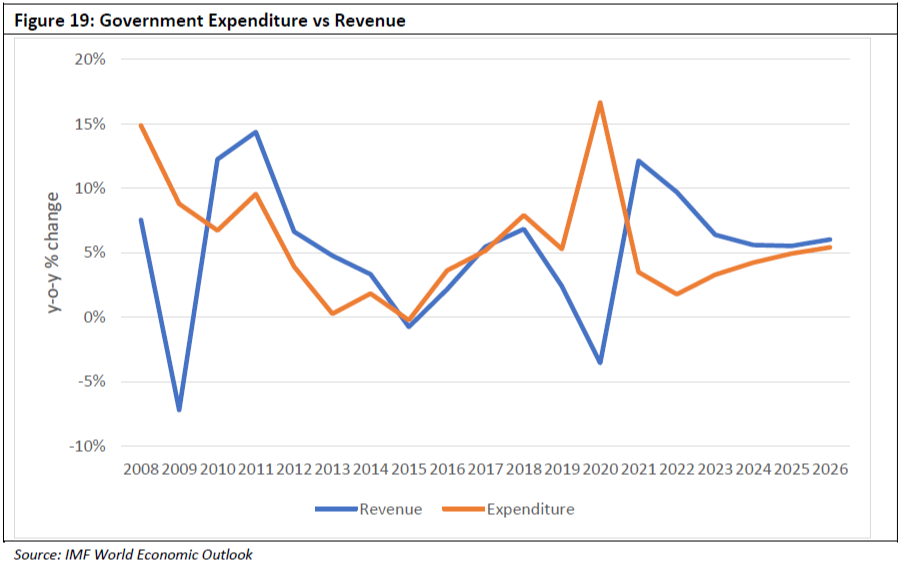

In order to support overall aggregate demand, total government expenditure increased by 16.7 percent year-on-year in 2020 while at the same time revenues dropped by 3.6 percent. In 2020 government expenditure stood at 39.6 percent of regional GDP but is expected to drop down to 37 percent this year.

As economies begin to recover government revenues are expected to recover as shown in Figure 19 but they remain at around 29 percent of GDP and expenditures will fall back to historical norms of around 35 percent of GDP by 2022. Rising inflation may see debts rolled over during a higher interest rate environment stressing economies with higher debt servicing obligations.

Several initiatives are in place to support emerging and low-income economies responses to Covid-19, these include for example the Debt Service Suspension Initiative, cited earlier, that allows eligible economies to focus their resources on fighting the pandemic that has been in place since May 202033. Under the terms of the initiative, 73 economies are eligible for a temporary suspension of debt-service payments owed to their official bilateral creditors, the G20 has also called on private creditors to participate in the initiative on comparable terms.

Other initiatives include the allocation of the equivalent of US$650 billion of special drawing rights at the IMF to bolster international liquidity. Regional initiatives such as the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM) has also been bolstered with a financing capacity of USD240 billion34 while the US Federal Reserve has entered into bilateral U.S. dollar liquidity swap lines with nine central banks.35 Dialogue on these efforts provides not only a useful understanding of the technicalities behind them but also a strong signal of the commitment of governments to cooperation. G20 Finance Ministers have supported the DSSI and the expansion of the IMF’s allocation of SDRs. As APEC works through the implementation plan for its post-2020 agenda, the link between global initiatives and regional mechanisms is an item that needs further consideration.

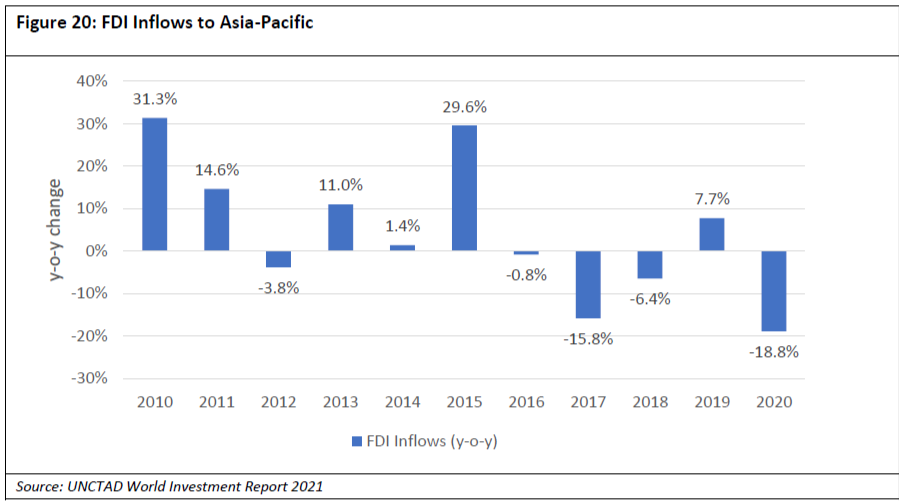

Foreign direct investment flows to the region fell by 19 percent year-on-year in 2020 (Figure 20), though it was significantly less than the drop in fall in global FDI flows.

A key issue for the recovery is if and when investor confidence will return. While governments have been able to help sustain demand over the crisis, a sign of the turning point will be when businesses are ready to start investing in jobs and capital.

While equity markets have been bullish, has this translated to increased investments from business in capital expenditure? Before Covid struck, the outlook for non-financial capital expenditure over 2020 and 2021 was negative, with G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors criticizing what they described as ‘excessive saving’ in the corporate sector. Some firms have needed that liquidity (and more) to survive the crisis but estimates show that the corporate sector continues to hold large cash balances, for example, Moody’s estimates that at the end of 2020 the US corporate cash pile increased to US$2.15 trillion, up 32 percent from the end of 2019.

The signs are very positive, and it appears that the cash will be spent not just on share buybacks and acquisitions but on productivity enhancing capital investment. Moody’s expects this to be between US$1.8 to US$1.9 trillion up from US$1.7 trillion in 2020.36 Globally, capital expenditure is expected to increase during 2021 from US$3.3 trillion to US$3.7 trillion37

The expectation is that the cycle of expenditure will be driven largely by investments in technology and sustainability with capital expenditure above 2019 baselines. However, not surprisingly there are some sectors where investment expectations remain negative – hotels, restaurants, and leisure stand out. This should be cause for concern given how many people these sectors employ in several regional economies.

Need for Balance

Some of the pressures in the global system arise from the continued policy-driven lock downs. The surge in demand for consumer durables, the continued closure and lack of certainty that hangs over a number of services sectors; and the lack of capacity in the transport sector.

The bounce back from 2020 has been unbalanced among sectors and economies, and will continue to be so unless specific policy actions are taken to rectify the situation. Careful consideration and analysis of the underlying causes is needed.

The worst-case scenario of stagflation is one that cannot be wished away. In the case that inflation is caused by a supply crunch – rises in interest rates will not increase the supply of semi-conductors or wheat. As argued here, the imbalance in demand has come from a temporary surge for specific products as a result of the pandemic. As economies open up, this will change, and the sooner governments find ways to open up, inflationary pressure will ease. Some central banks are carefully watching wages, Christine Lagarde of the ECB, for example said “we will pay close attention to wage developments and inflation expectations to ensure that inflation expectations are anchored at 2%.”38. Problematic again is the K-shape of the recovery, historically wage increases have not kept up with productivity39.Wage increases for lower deciles would be welcome and overdue – and resolve some of the problems with inclusive growth.

The focus should therefore be on dealing with the structural inefficiencies that the pandemic has laid bare as well the longer-term issues that the region has identified as its priorities. For example, this year APEC adopted an Enhanced APEC Agenda for Structural Reform (EAASR). This outlines four pillars of work:

- Creating an enabling environment for open, transparent, and competitive markets;

- Boosting business recovery and resilience against future shocks;

- Ensuring that all groups in society have equal access to opportunities for more inclusive, sustainable growth, and greater well-being; and

- Harnessing innovation, new technology, and skills development to boost productivity and digitalization.

Over the medium term these provide an ideal framework for developing the policy tools for dealing with the supply side issues at the heart of the problem. Each of these are large set of issues, but the value of the APEC approach is that enables its members to focus on one or two areas of particular concern, and report back to the community on the progress they are making. Some of these are done collectively through exercises such as the APEC Conferences on Good Regulatory Practices and the APEC Economic Policy Reports. Greater coordination and synergy between the Economic Committee and Finance Ministers track is necessary. For example, work on corporate governance and ESG standards would be an area of common interest.

Proximate concerns of the pandemic will occupy policy-makers but decisions being taken now are having longer-term consequence. Globalization has been a moderating force on inflation for the past few decades and its reversal will have exactly the opposite effect.

Priorities for Dealing with Covid-19 and Its Consequences

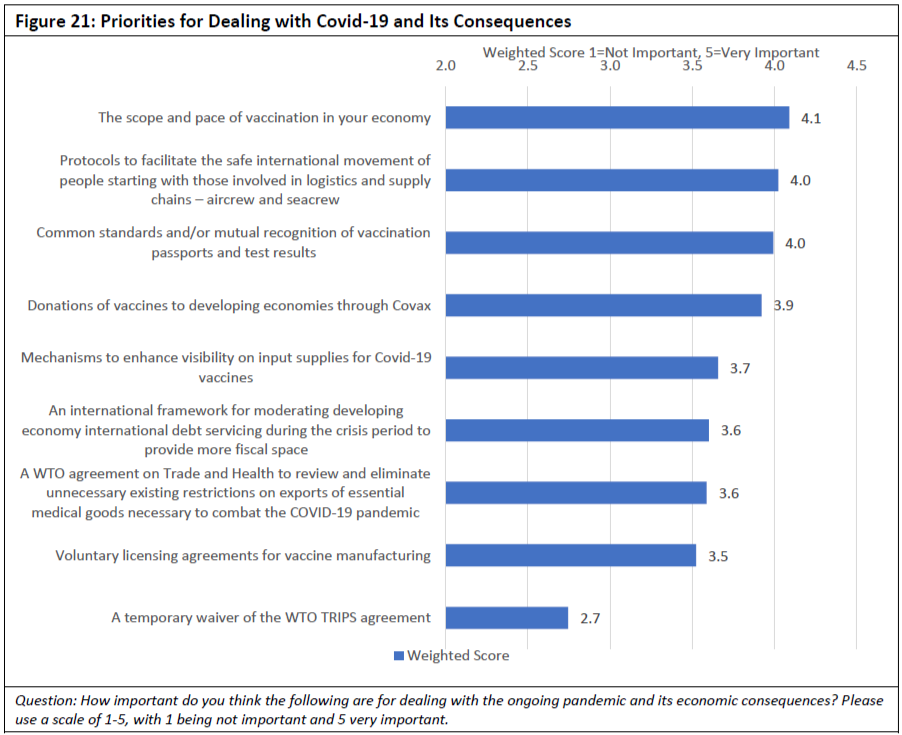

PECC’s survey of the policy community sought their views on the priorities for dealing with the pandemic. Results are reported in Figure 21.

Overall, the most important issue among survey respondents was the scope and pace of vaccination, which had a weighted score of 4.1 on a scale of 1 to 5 or with 78 percent of respondents (see Annex for detailed survey results) selecting it as important or very important for dealing with the pandemic and its economic consequences. This was followed by issues related to the movement of people: protocols for the safe movement of those involved in logistics – aircrew and seacrew and then common standards for and/or mutual recognition of vaccination passports and test results.

However, there were some differences in priorities between emerging and advanced economies. Donations to Covax was the second highest priority for emerging economy respondents, common standards and/or mutual recognition of vaccination passports and test results was the top priority for respondents from advanced economies.

This did not mean that it was ‘unimportant’, just relatively less important, for example, on the issue of donations to Covax, 67 percent of advanced economy respondents selected it as important or very important, whereas 73 percent of them selected protocols for the safe international movement of people as important or very important.

Issues that have been or are currently being debated such as a temporary waiver of the WTO TRIPS agreement, a WTO agreement on Trade and Health, or international frameworks for moderating developing economy international debt servicing during the crisis which has been discussed by the G20 came further down in the list of priorities.

Other than vaccination, the priorities that emerged were issues where there has been little international cooperation or rather little progress thus far.

On the other hand, business respondents did not see a temporary waiver of the WTO TRIPS agreements as important as government or non-government respondents. There was much less of a gap between business and government views on the importance of voluntary licensing agreements for vaccine manufacturing, underscoring the complexity of the landscape of policy issues.

The Scope and Pace of Vaccination When APEC Leaders met at the end of 2020, they highlighted the importance of “facilitating equitable access to safe, quality, effective and affordable vaccines” and acknowledged that “the role of extensive immunization against COVID-19 is critical in order to bring the pandemic to an end. Since then considerable progress has been made with now approximately 40 percent of the region’s population fully vaccinated.

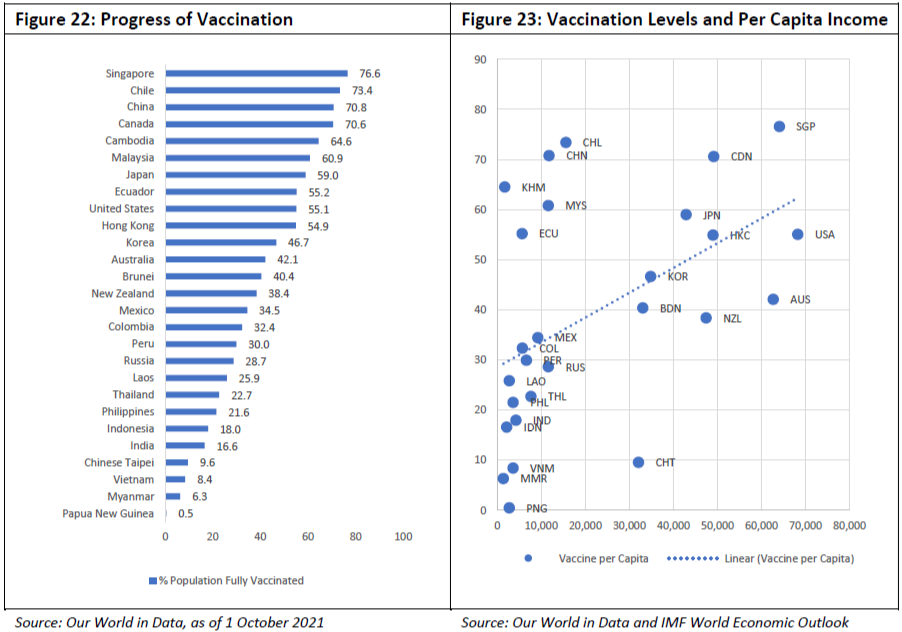

However, the process has been far from even with some economies managing to achieve vaccination rates of over 70 percent to date with many others well below 40 percent (Figure 22). While the global discourse has focused on the differences between high and low income economies, the story in the Asia-Pacific is mixed.

Some middle-income economies such as Chile have moved very quickly to vaccinate over 70 percent of their population, much faster than higher income economies (Figure 23). Chile was not only an early mover but took a portfolio approach to its effort, entering into deals with Sinovac, Pfizer, and Astra Zeneca, Johnson and Johnson in late 2020 as well as CanSino in the first quarter of 2021. Higher income economies that relied on a smaller set of vaccines have had to wait for deliveries.

The number of vaccines approved, speed of domestic regulatory approval, the nature of the contract with the manufacturer, domestic systems delivery system, the availability of cold chain facilities, the size of population as well as vaccine hesitancy have all played a role in the ability of economies’ ability to quickly deliver Covid-19 vaccines to their populations.

In recent months, the Asia-Pacific has been vaccinating around 12 million people a day. To reach the goal of 70 percent vaccination, that would take another 100 or so days at current rates – assuming vaccines are available. The rate of vaccination will inevitably slow as the easier to access and more willing population have been received shots. A paper by World Bank experts analyzing vaccination trends in Asia contends that “as vaccination coverage increases, distribution to remote areas is likely to vary and vaccine hesitancy to become a binding constraint… Therefore, the attainment of these goals cannot be taken for granted and will continue to require a special effort to acquire vaccines, distribute them, and persuade people to get vaccinated.”40 Two key points emerge from their analysis:

- Sustained emphasis on non-pharmaceutical interventions, especially testing, tracing, and isolation.

- Since zero COVID-19 may not be an affordable option, health systems need to be adapted to live with long COVID.

Our definition of Asia-Pacific here is broad, taking in the members of APEC, ASEAN, the East Asia Summit and PECC – a region of 4.5 billion people. Broad as it is, it is also the most useful given how the pandemic has evolved and spread across borders. Just as conceptually the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific needs to take into account the reality that its pathways such as the RCEP includes non-APEC ASEAN members, APEC’s concept of open regionalism can serve it well in dealing with what are complex issues such as pandemics and connectivity.

Thus far APEC leaders have agreed to laudable language on equitable access to safe, effective, quality-assured, and affordable COVID-19 vaccines but without any specific targets on what equitable might mean within the regional context. The headline number of 41 percent might be reassuring but underlying these are very low vaccination rates in some economies that leaves them extremely vulnerable and belies the spirit of community that APEC is intended to engender. Moreover, it is in these contexts that new variants emerge – according to the WHO “when a virus is widely circulating in a population and causing many infections, the likelihood of the virus mutating increases. The more opportunities a virus has to spread, the more it replicates – and the more opportunities it has to undergo changes.”41

A further issue is ‘booster shots’ especially for vulnerable members of society in economies with relatively high vaccination rates and the issue of global equity. Here global coordination and science-based approaches will be critical. While the medical advice on boosters is hotly debated. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control has stated that “Special consideration should be given to the current global shortage of COVID-19 vaccines, which could be further worsened by the administration of booster COVID-19 vaccine doses.” 42 While others, including the U.S. president and his chief infectious disease expert, contend that both boosters for the vulnerable and vaccine equity can be done.

The reality is that large swathes of the global population are yet to receive a single dose of vaccine including in the Asia-Pacific. This not only affects their own vulnerability, but increases the risk of the emergence of new, more virulent strains of the virus affecting others. While most vaccines also protected those vaccinated against severe disease in the case of the Delta variant, this may not be the case with future variants.

APEC Leaders can make it a clear and unambiguous goal to have 40 percent of the Asia-Pacific population vaccinated in every economy by the end of 2021 with 70 percent vaccinated by the first half of 2022. In doing so this would begin a conversation on where in the region help needs to be given and resources directed whether bilaterally, or through multilateral development banks.

The examples in the region demonstrate that highest income levels are not a necessary pre-determinant of successful vaccination campaign and are worth of further analysis.

Protocols to Facilitate the Safe Movement of Supply Chain Workers

Protocols to facilitate the safe movement of people – starting with those involved in logistics and supply chains was second highest in the list of priorities. While regional and global leaders see the movement of goods as a priority, little has been said about the people that make international trade happen. The patchwork of rules has reached such a crisis point that the International Air Transport Association, the International Chamber of Shipping, and the International Transport Workers’ Federation have called on world governments to deal with these issues. They argue that:

- transport workers be given priority to receive WHO recognized vaccines; and

- heads of government work together to create globally harmonized, digital, mutually recognized vaccination certificate and processes for demonstrating health credentials (including vaccination status and COVID-19 test results), which are paramount to ensure transport workers can cross international borders.

The fragmented system of restrictions is bringing the world trading system to a breaking point and severely impacted global supply chain and put at risk the health and wellbeing of the international transport workforce.

The International Maritime Organization and the International Civil Aviation Organization have issued sets of recommendations and protocols that would address specific concerns of authorities for these network industries. While those in the aviation sector are likely to cross borders more often than those in the maritime sector, they both require international frameworks given the nature of the industries. The problems facing the sectors are different but both require international cooperation to solve them.

The cumulative impact of the Suez Canal blockage, Covid-19 related shutdowns means that global transport and trade systems need to be adjusted to ensure the smooth flow of goods and services required for this.

Although the congestion in global shipping cannot be traced to a single cause as discussed earlier, one key issue that must be addressed is the workers in its eco-system. The United Nations has described it as a humanitarian crisis; at the high point as many as 400,000 workers were stranded at sea due to flight cancellations and border closures. But it is also a trade and economic issue with 90 percent of global trade by volume carried at sea and only 15.3 percent of seafarers vaccinated as of August.43

Around 63 percent of seafarers come from the Asia-Pacific, many of these come from emerging economies that depend on Covax for vaccines. The United States and Singapore are among APEC economies have recognized this and have taken the initiative to provide vaccinations for foreign sea-crew.44 Regional processes that have committed to keeping goods flowing such as APEC, ASEAN and the East Asia Summit could support this by putting into practice the IMO’s recommendation to:

- Designate professional seafarers and marine personnel as key workers providing an essential service working on vessels are designated as essential workers

The International Chamber of Shipping says that only 55 economies have done so, and this needs to change to keep supply chains running safely and securely. The WHO has named seafarers as one of the groups of transportation workers to be prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination in instances of limited supplies. This would help to prevent the spread of the virus and help to limit closures of ports as discussed above.

While the number of seafarers impacted by travel bans has decreased from 400,000 last year, the emergence of new Covid-19 variants again threatens to leave workers stranded on vessels working beyond 11 months. 45

APEC needs to respond to this call for action. The agenda is critical to core APEC business – trade. The following items need to be considered:

- Designation of those working in supply chains as essential workers

- Mutual recognition of tests/vaccine certification for transport workers

- Identification of capacity building needs and gaps in implementation of ICAO transport corridors and IMO framework protocols

- Making vaccines available to foreign transport workers by all APEC economies

APEC’s tried and tested public-private dialogues can help to shed light on specific issues economies, businesses, and stakeholders are facing during these times to minimize frictions in the running of supply chains.

Common Standards for Travel

Common standards and/or mutual recognition of vaccination passports and test results ranked third in the list of issues for dealing with the ongoing pandemic and its economic consequences.

The standards that authorities are following differ, sometimes tests need to be done 48 hours before departure, sometimes 72 hours. For vaccinated travelers there are questions on whether their vaccine is ‘recognized’ – even if that recognized and indeed widely used in the destination, it may be that the destination simply does not recognize the authority that has administered the traveler’s vaccine.

In short, there is a spaghetti bowl of regulations that travelers face. Even as and when the WHO declares the pandemic officially ended, the likelihood is high that those regulations will still be in place.

Increasingly travel is becoming contingent on proof of status of test results and/or vaccination. Solutions are available, IATA, for example has a travel pass initiative that airlines can join to allow passengers to present proof of health status. 46 The International Chamber of Commerce has developed AOKPass using blockchain technology47. The European Union is now using a Digital COVID Certificate.48

The risk for the recovery is that sets of regulation become unnecessarily burdensome and lack interoperability. The cost to jobs and the economy is likely to be high, an estimated 62 million jobs in the travel and tourism industry were lost during the pandemic. While economies are beginning to open, unless efforts are made to reduce frictions in the system, significant scarring will occur and those job losses will become permanent.

In the Asia-Pacific individual economies are launching individual initiatives but there is no coherent approach. ASEAN is reported to be discussing a digital vaccine certificate.49 APEC members have discussed facilitating safe passage and the APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC) has called for a regionally consistent framework to minimize the cost and complexity of resuming business travel when the Covid-19 situation allows.

Travel and Tourism

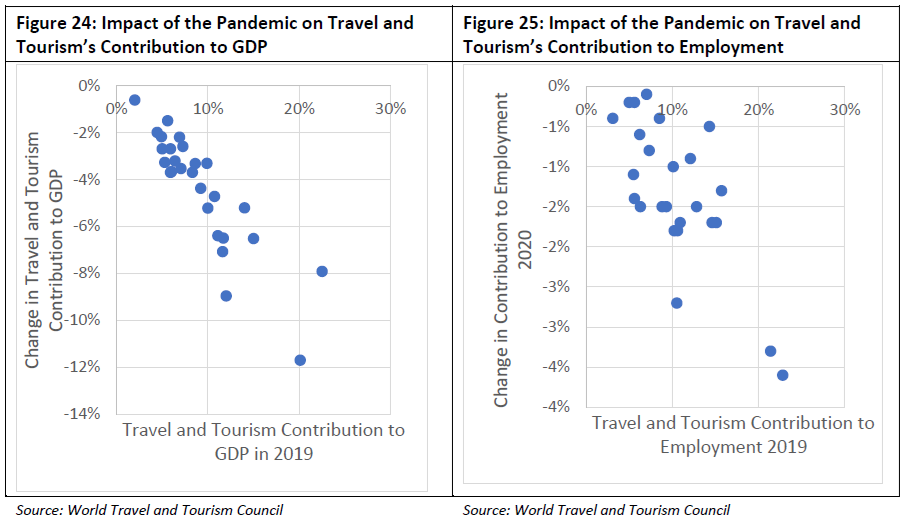

Prior to the pandemic the travel and tourism sector employed 334 million people globally and accounted for around 10 percent of global GDP. In the Asia-Pacific the sector employed 208 million people, in 2020 some 40 million or 20 percent of those jobs were lost according to estimates by the World Trade and Tourism Council.50 The impact of the of the jobs losses has been uneven across the region with job losses above 30 percent in some economies.

The travel and tourism sector contributed around 9 percent to the region’s GDP in 2019, in 2020 this fell to under 5 percent in 2020. In 2019 the sector had contributed US$5.4 trillion to the region’s economic output but in 2020, this fell to US$2.7 trillion. Figure 24 shows the change in the travel and tourism sector’s contribution to regional economies’ GDP in 2019 and the change in that contribution from 2019 to 2020. Generally speaking the larger the sector the bigger the fall has been among regional economies although there have been significant differences. This may be due to larger for example, domestic tourism. Figure 25 shows a similar story for the sector’s contribution to employment although the relationship between the size of the sector and the change is not as large.

The airline sector itself showed some improvement around the second quarter of 2021, with domestic travel rebounding somewhat as some economies began to re-open, however, as with other sectors of the economy, concerns about the spread of the Delta variant have affected the airline sector.51 The International Air Transport Association expects the sector to continue to make losses through 2021 in spite of the economic recovery through 2021.

More than 40 airlines have filed for bankruptcy including regional airlines such as Virgin Australia, Philippine Airlines, LatAm, Avianca and Aeromexico. While governments have come to the assistance of the airline sector as a result of the crisis, the OECD finds that the type of assistance has varied, but is not likely to change the landscape of ownership immediately. However, governments may find themselves unintended owners of bankrupt air transport companies.52 Furthermore, consideration needs to be given to the ultimate changes taking place in the competitive landscape of air cargo services that are being driven by technological as well as business model changes.53

However, while industry has been able to respond by increasing capacity, finding it is a challenge

“it also highlights the need for clarity on government plans for a safe industry restart. Understanding how passenger demand could recover will indicate how much belly capacity will be available for air cargo. Being able to efficiently plan that into air cargo operations will be a key element for overall recovery,”.54

The APEC Policy Support Unit estimates that the GDP losses for the region from lost cross-border movement and unrealised economic activity at US$1.2 trillion.55

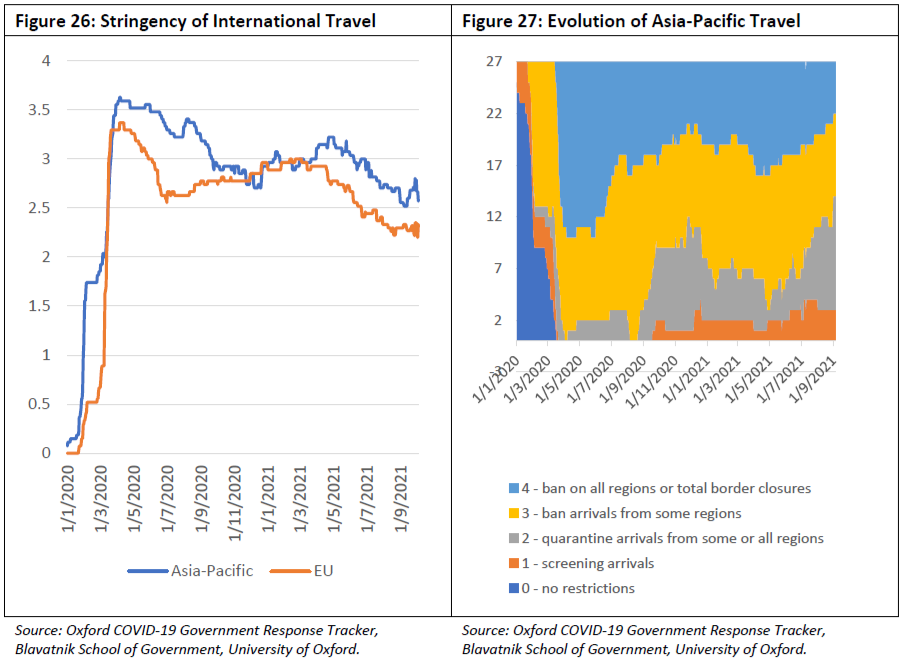

Governments across the world are taking different approaches to international policy. The EU is significantly more open in its approach to travel than the Asia-Pacific (Figure 65). Within the region, there are large differences with 40 percent of economies opting to quarantine arrivals from some or all regions, while around 30 percent maintain bans from some regions; and another 20 percent have total border closures. (Figure 27) The rationale for continued restrictions is also questionable, analysis of the impact of closures finds that

“stringent travel restrictions might have little impact on epidemic dynamics except in countries with low COVID-19 incidence and large numbers of arrivals from other countries, or where epidemics are close to tipping points for exponential growth.”56

On 2 July 2021 the WTO issued “Policy considerations for implementing a risk-based approach to international travel in the context of COVID-19”

- not require proof of COVD-19 vaccination as a mandatory condition for entry to or exit

- consider a risk-based approach to the facilitation of international travel by lifting measures, such as testing and/or quarantine requirements, to individual travellers who:

- 1) were fully vaccinated, at least two weeks prior to travelling, with COVID-19 vaccines listed by WHO for emergency use or approved by a stringent regulatory authority or

- 2) have had previous SARS-CoV-2 infection as confirmed by real time RT-PCR (rRTPCR) within the 6 months prior to travelling and are no longer infectious as per WHO’s criteria for releasing COVID-19 patients from isolation. The use of serologic assays is not recommended to prove recovery status given the limitations that are outlined in the scientific brief “COVID-19 natural immunity”.

- if testing and/or quarantine requirements are lifted for travellers who meet the abovementioned criteria, offer alternatives to travel for individuals who are unvaccinated or do not have proof of past infection, such as through the use of negative rRT-PCR tests, or antigen detection rapid diagnostic tests (Ag-RDTs) that are listed by WHO for emergency use or approved by other stringent regulatory authorities

- consider recording proof of COVID-19 vaccination in the International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP), as stated in the WHO interim position paper: considerations regarding proof of COVID-19 vaccination for international travellers. Authorities may also use other certificates of COVID-19 health status, some in digital format, as recommended by regional or global intergovernmental bodies. Where digital certificates of “COVID-

A review of those economies that are opening up shows that governments are however, asking for proof of vaccination as a condition for entry. 57

The World Committee on Tourism Ethics, an independent advisory body of the General Assembly of the UN World Tourism Organization has issued recommendations for COVID-19 Certificates for International Travel which state that:

- The certificate should be a unique document, containing information on the vaccination status, and/or diagnostic (molecular, PCR and antigen) and/or information about recovery status;

- The certificate should be limited in duration and its use should be discontinued as soon as the World Health Organization no longer considers COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC);

- The certificate should be used primarily for international mobility;

- For a maximum accessibility, the certificate should be available both in digital and paper format;

- The certificate must ensure, in both formats, data protection and security, as well as the privacy of the holder. Said certificate must also provide a guarantee of authenticity to avoid fraud and misuses;

- The certificate should be free of charge; international cooperation and governments should ensure the population’s wide access to free vaccines and affordable tests;

- The provision of vaccines and related certificates at destination countries should not form part of package tours or other similar products nor should such initiatives be supported by governments

Even within those groupings there are differences, for example, some require proof of vaccination and/or test results, the duration of quarantine varies from 7-14 days, and the justification for travel varies – ie business travel is sometimes permitted. This begs the question of what types of test or vaccination proof would be accepted by immigration authorities and then which vaccinations would be recognized?

This is leading to substantial difficulties for authorities that have begun the process of opening up. For example, some economies have opened to vaccinated travellers from some economies but not to others who have received substantially the same vaccines. While the EU has developed its Digital Covid Certificate, the African Union has developed an online portal as well as a mobile application to facilitate cross-border travel and inform the public on regulation changes with several members joining the initiative. 58

The Covid-19 experience underscores the need for a holistic understanding of the connectivity eco-system that underpins global trade. While UNCTAD produces an annual review of the Maritime Transport, no organization provides such a review of the air cargo sector.

The mid-term review of the APEC Connectivity Blueprint showed that the region’s average score for the perceived quality of air transport infrastructure showed a decline over the 2014-2017 period, while research by IATA estimates that a 1% improvement in air cargo connectivity translates to a 6.3% increase in trade.59 Given the likely long-term trend towards high-volume low-value shipments via air, and as well as considerations of at least a medium-term term towards higher prices in shipment due to less belly capacity due to fewer tourists, the sector is likely in for a shakeout. These have been limited to Europe and North America but fast-growing consumer markets in Asia and South America where growth of digital trade alternatives is rapid are not likely to be far behind. Amazon Air flights increased from just 85 daily flights in May 2020 to 140 a day in February 2021. 60

Echoing the connection between travel restrictions and trade costs, the OECD estimates average increase in trade costs of services is 12 percent. However, these vary by economy and sector. Repealing the restrictive measures introduced to address the current sanitary crisis, as conditions permit, will therefore be an important consideration in promoting sustainable economic recovery. They find that remote work can reduce costs by 3.5 percent in some sectors – but it has no impact in sectors that require travel such as the transport sectors.

While some regions have begun to restore flights, the Asia-Pacific largely lags behind lacking any mechanism for mutual recognition of test results or vaccinations. This leaves it extremely costly as well as confusing for travellers who confront ever changing sets of rules for international travel.

APEC’s long experience in regulatory cooperation, working on standards to facilitate interoperability between different regimes must be mobilised. While economies are at different stages with respect to the pandemic, the risk is that divergent policies will introduce an entirely new set of barriers to connectivity and trade. The region risks an imbalanced recovery if these issues are not dealt with. Unless APEC members work together to ensure that new regulatory systems are interoperable, new costs will be added to trade and people movement undoing decades of work.

Donations of vaccines to developing economies through Covax

Donations of vaccines to developing economies through the Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access (Covax) was 4th in the list of priorities. Although it ranked 2nd in the list of priorities for respondents from emerging economies. Coordinated by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), and the World Health Organization (WHO), Covax was intended to provide a mechanism to reduce the cost of vaccines for all. The system (and governments) have come under considerable criticisms with many economies bypassing Covax entering bilateral deals.61 That said, it still provides millions of vaccines to those who cannot afford and provides a clearing mechanism for assistance.

Mechanisms to enhance visibility on input supplies for Covid-19 vaccines

Overall 64 percent of respondents thought that it was either important or very important to have mechanisms that enhance visibility on input supplies for Covid-19 vaccines. PECC’s Special Report on Covid-19 last year had recommended a system modelled on the G20 Agricultural Market Information System to create greater visibility on the medical supply chains. 62 Earlier this year, Covax established a Manufacturing Task Force to address bottlenecks in supply chains,

WTO Agreement on Trade and Health

A group of members have tabled an initiative at the WTO that would commit members to:

- review and promptly eliminate unnecessary existing restrictions on exports of essential medical goods necessary to combat the COVID-19 pandemic; and

- exercise restraint in the imposition of any new export restrictions, including export taxes, on essential medical goods and on any prospective vaccine or vaccine materials.63

Some argue that such an initiative should go beyond trade and include investment to subsidize the full vaccine manufacturing supply chain and especially coordinate expansion of input production capacity.64 APEC members substantively agreed to the first component and more in their Statement on COVID-19 Vaccine Supply Chains.

TRIPS Waiver & Voluntary Licensing Agreements

WTO members have been discussing a proposal to waive certain patent obligations under the WTO TRIPS agreement to scale up production of Covid-19 vaccines. 65 There is debate on how meaningful this would be in producing vaccine in new locations.

Another way of scaling up production is through voluntary licensing agreements in which the patent holder voluntarily grants to manufacturing facilities in lower cost manufacturing facilities or through pooling such as the WHO initiative the Covid-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP).66

Interestingly, voluntary licensing was preferred by respondents from both emerging and advanced economies from the Asia-Pacific, 68 percent of emerging economies respondents thought that voluntary licensing was important or very important compared to 41 percent for the temporary TRIPS waiver. While 49 percent of respondents from advanced economies thought that voluntary licensing agreements were important or very important compared to 28 percent for a temporary TRIPS waiver.

Digital Economy

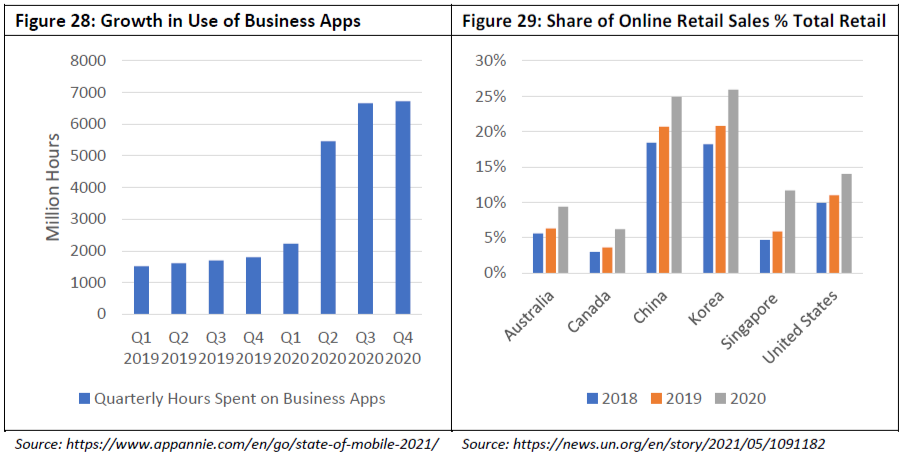

As economies have implemented social distancing policies to stem the spread of the pandemic businesses, schools and governments have accelerated digital adoption plans with estimates showing a 5-8 years’ worth of transformation in the first 2 months of the pandemic. As shown in Figure 28, the number of hours spent on business apps increased exponentially during 2020. In 2019 mobile users were spending an estimated 1.8 billion hours on these apps per quarter, this rose to over 5.5 billion hours during the second quarter of 2020 and by the end of 2020 was at around 6.7 billion hours.

This change in the way people work is expected to be one of the lasting features of the post-Covid reality. 67Another change to the landscape has been the rapid digitalization of the retail sector. UNCTAD estimates that online retail sales share of total retail jumped in 2020 across all economies from 16 to 19 percent. As seen in Figure 28 the online share is uneven across a select few regional economies where data was available and there is still significant growth to be had.

One of the big benefits of firms going digital is that it opens up global markets to them, analysis of US small businesses on the eBay platform shows that 97 percent of them export compared to only 1 percent of traditional businesses reaching an average of 17 different markets. 68

Estimates of the size of the digital economy range from a low of 4.5 to 15.5 percent of world GDP, while the share of digitally delivered services in total services exports has risen from 45 percent to 52 percent between 2005 and 2019.69 That share is likely now much higher given the massive increase in digital onboarding that has taken place over the pandemic.

Well before the crisis struck, regional leaders had adopted an Internet and Digital Economy Roadmap to promote cooperation on developing the internet economy and facilitate technological and policy exchanges to bridge the digital divide. The digital economy was recognized as one of the 3 drivers to achieve the Putrajaya Vision.

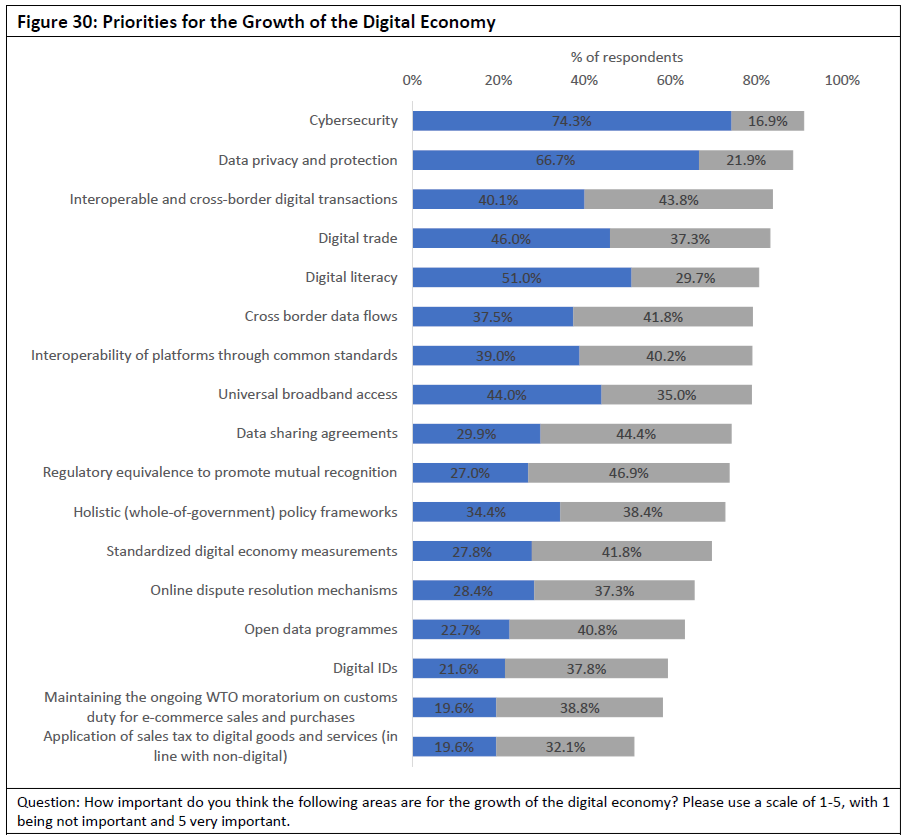

To get a sense of what the policy community’s priorities were for the growth of the digital we asked respondents for their views on the importance of a range of issues to the growth of the digital economy (Figure 30).

The top issue as measured by the percentage of respondents who thought the issue was either important or very important were:

- Cybersecurity

- Data privacy and protection

- Interoperable and cross-border digital transactions

- Digital trade

- Digital literacy

In a recent report by UNCTAD, UN Secretary General António Guterres said that “The current fragmented data landscape risks us failing to capture value that could accrue from digital technologies and it may create more space for substantial harms related to privacy breaches, cyberattacks and other risks.”70.

APEC’s Roadmap on the Internet and Digital Economy covers all of these issues, however, there are challenges in making progress on them.

Access issues remain a concern with 79 percent of respondents selecting universal broadband access as important to very important. While broadband access has improved significantly over the years especially in mobile, fixed broadband penetration remains relatively limited at about 19 percent of the population. According to GSMA, a telecoms industry grouping, significant growth in the sector is expected especially with the development of 5G technology. They expect to spend US$900 billion from 2021-2025 in capital expenditure globally and the internet of things to growth significantly from 13.1 billion connected devices to 24 billion devices. 71 The pace of 5G adoption is expected to vary across with region, in parts of Southeast Asia and Oceania over the next 5 years, 5G is expected to increase from just 1 percent to 12 percent of mobile traffic, while in China, Hong Kong (China), Chinese Taipei and North America around 50 percent.

The Covid-19 crisis has clearly underscored the use case for 5G with users looking to use it to replace fixed broadband, and for video-calling, tv and video services, remote health, shopping and other services. The shift to online activities – including learning, work, shopping, entertainment and social interactions – is evidenced by the sharp growth in internet usage with mobile network traffic up 50% year-on-year during the peak of the pandemic.

In Southeast Asia online consumer expenditure has grown by 60 percent to reach US$238 and is expected to reach US$671 by 2026 according to a report by Facebook and Bain and Company. The pattern of online consumption is shifting from streaming and ride-hailing to healthcare, food delivery and grocery shipping. According to the same report, e-wallets are now the preferred payment option for 37 percent of consumers compared to 28 percent who said they still prefer to use cash.

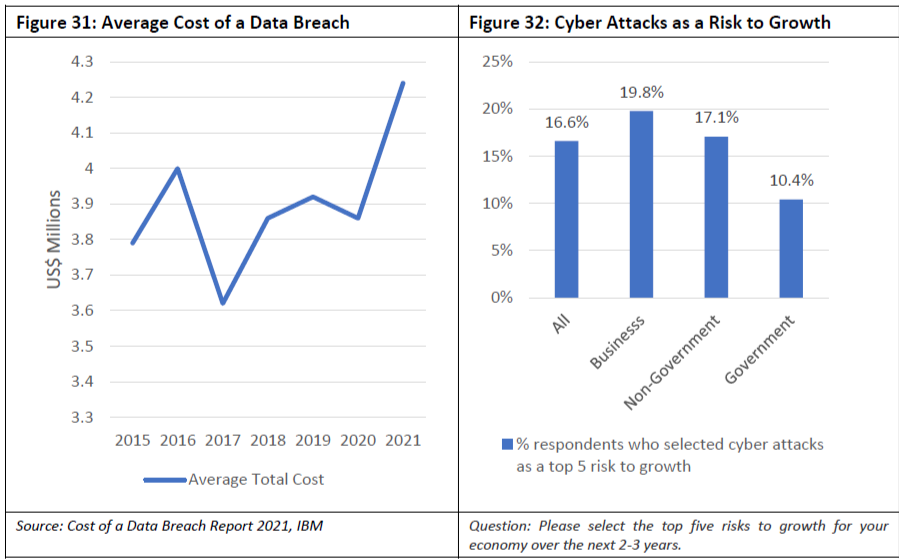

Importantly, security concerns were the top reason why people were reluctant to shift to using online. A rising concern during the pandemic has been escalating cybercrimes -highlighted by the fact that cybersecurity was the top issue for respondents for the growth of the digital economy. While one of the biggest benefits of the digital economy has been its ability to increase inclusion and reduce transactions costs, the downside is cybercrime.

Although it is not a top 5 risk to growth, there were considerable differences among stakeholders on this issue, with 20 percent of business respondents selecting cyber-attacks as a risk to growth compared to just 10 percent of government respondents (Figure 29). This indicates the need for public-private dialogue on this issue to bridge the difference and build a better understanding of how this issue impacts business. Interpol believes that that the trend in cyber-crimes is likely to rise exponentially over the coming years, just as businesses and societies go online so will crime. Cybersecurity experts project the total net cost of cybercrime to grow by 15 percent per year over the next five years, reaching USD 10.5 trillion annually.

Cybercriminals have also taken advantage of the fact that more people accessed the Internet with mobile devices (that are often left unprotected) to enable remote working, shopping and transactions in the wake of COVID-19. This made users vulnerable to becoming targeted because attackers were taking a more customized approach and targeting specific geographical areas, industries and businesses and were also taking advantage of the desire for more COVID-related information.72

IBM estimates that the average cost of a data breach is around US$4.2 million, however, this varies considerably by industry with costs greater for more regulated sectors like healthcare, energy and financial services. Around 52 percent of data breaches are caused by malicious attacks. (Figure 31)

There have been significant developments in the Asia-Pacific with the entry into force of the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) among Chile, Singapore and New Zealand. The first ‘digital only’ economic agreement among economies that cover a wide set of issues such as SMEs, digital identities, cross border data flows, paperless trade and emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence.

Interestingly the parties to the agreement chose to describe each section as ‘modules’ rather than as chapters unlike traditional trade agreements marking a break from past practice. Article 16.4 of the agreement specifies terms of accession which make it an open agreement – with only agreement of the parties required. On 12 September Korea formally announced its intention to join the agreement,73 while Canada has been undertaking public consultations on its accession. 74 These moves add considerable weight and momentum to what was initially a small agreement.

ASEAN Economic Ministers at their meeting on 8-9 September endorsed the Bandar Seri Begawan Roadmap: An ASEAN Digital Transformation Agenda to Accelerate ASEAN’s Economic Recovery which includes agreement to study the establishment of an ASEAN Digital Economy Framework Agreement (DEFA) by 2023 and to commence negotiations on the DEFA by 2025.

The Pacific Alliance has also set out a roadmap for its digital agenda with the goal of creating a regional digital market with four pillars: (i) digital economy; (ii) digital connectivity; (iii) digital governments; (iv) digital ecosystems.

With DEPA in place, a potential ASEAN DEFA negotiation, and a Pacific Alliance Digital Market, the question is where APEC can go with its work on the digital economy? PECC’s earlier recommendation was for APEC to prioritise “the urgent development of understandings and consensus leading to development of a unified Asia-Pacific digital market by 2030”75 as part of its post 2020 work. Such work would prevent the fragmentation of the digital economy one of the key concerns of stakeholders in the region.

The cost of the fragmentation of the digital economy are likely to be extremely high. As demonstrated by our survey results, stakeholders are deeply concerned that the growth of the digital economy will be constrained by the lack of interoperability. While initiatives are under way in the Asia-Pacific to develop rules for the digital economy that address issues such as cybersecurity, digital trade, and privacy, they remain largely fragmented – APEC could play a substantial role to bring greater understanding of the different regulatory approaches to this rapidly growing part of the economy and ensure that they adhere to generally accepted principles for trade – transparent, non-discriminatory and least trade restrictive.

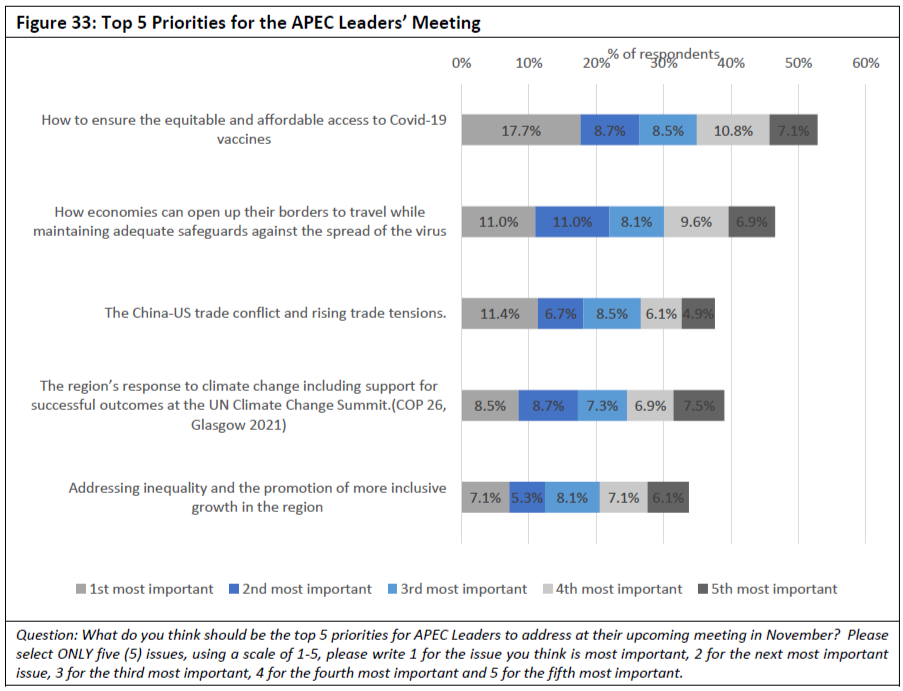

Priorities for APEC Leaders’ Meeting

When APEC Leaders gather in November, in addition to dealing with an ongoing pandemic, they will be meeting during a sequence of high-profile international events: the G20 Summit, the UN Climate Change Conference – COP 26, the East Asia Summit and the 12th WTO Ministerial Conference.

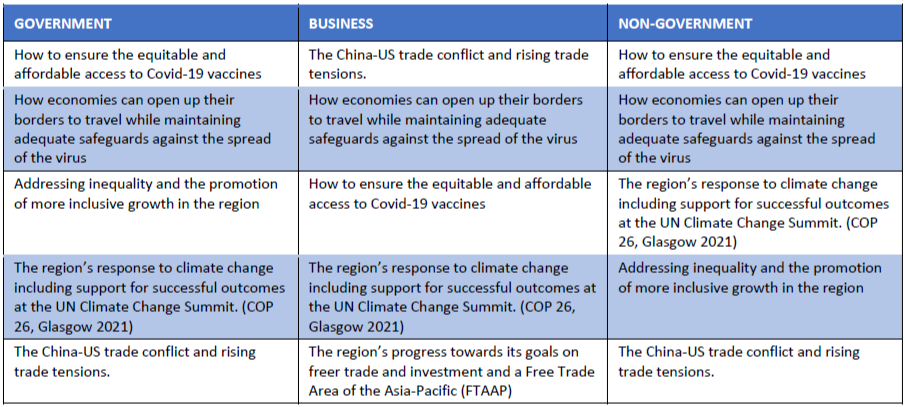

Pressure will be high for this summitry to deliver meaningful outcomes. For APEC, out of a list of 19 issues and initiatives that included both global issues such as the pandemic, climate change as well as issues specific to the APEC agenda such as an implementation plan of APEC’s post-2020 vision and progress on a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific, the top 5 were (Figure 33):

- How to ensure the equitable and affordable access to Covid-19 vaccines

- How economies can open up their borders to travel while maintaining adequate safeguards against the spread of the virus

- The region’s response to climate change including support for successful outcomes at the UN Climate Change Summit. (COP 26, Glasgow 2021)

- The China-US trade conflict and rising trade tensions.

- Addressing inequality and the promotion of more inclusive growth in the region

Clearly stakeholders expect leaders to focus on Covid-19 issues – both how to deal with the problem of vaccine inequality as well as how economies can safely open their borders to travel. At the same time there is a strong hope that the Asia-Pacific can deliver meaningful input to global climate change discussions while addressing problems of inclusive growth. Equally there is a view that progress requires cooperation between the region’s two biggest economies the United States and China.